June 6, 2000 “One gang was as bad as another,” says an old woman at the end of Istvan Szabo’s “Sunshine.” In her long lifetime in Hungary she has lived under the emperor, the Nazis and the Communists. And she watched as the West betrayed the 1956 uprising. She has watched some members of her Jewish family spend the century trying to accommodate themselves to the shifting winds of politics and society, and failing. She has seen other members fight against the prevailing tyrannies, only to find them replaced by new ones.

And she has witnessed the Holocaust bearing down over three generations–not as an aberration, a contagion spread by Hitler, but as the inexorable result of long years of anti-Semitism. We are reminded of the 1999 documentary “The Last Days,” also about Holocaust victims in Hungary, which observes that the persecution of the Jews there began fairly late in the war, at a time when Hitler’s thinly stretched resources were needed for tasks other than genocide.

But the Nazis had help. “Nice ordinary Hungarian people did the dirty work,” we learn, and there is even the possibility that some members of the Sonnenschein family, which the movie follows over three generations, would have helped, had they not been Jewish and therefore ineligible. The movie shows family members determined to think of themselves as good Hungarians. The family name is changed to Sors to make it “more Hungarian,” and Adam Sors, in the middle generation, converts to Catholicism, joins an officers’ club, and wins a gold medal for fencing in the Olympics.

But assimilation is not the answer, as he learns when he remains too long in Hungary, believing a national hero like himself immune to anti-Semitism. There is a heartbreaking scene in a Nazi death camp where he tells an officer that he is a loyal Hungarian army officer, too–and a gold medalist. “Strip,” the officer tells him, and soon his naked body has been crucified and sprayed with water until it forms a grotesque ice sculpture.

Szabo’s epic tells the story of one family in one country, but it will do as a millennial record of a century in which one bright political idea after another promised to bring happiness and only enforced misery. The Sonnenschein family fortune is founded on “Sunshine,” an invigorating tonic with a secret recipe. The film does not need to underline to symbolism that the formula for the tonic is lost as the century unfolds.

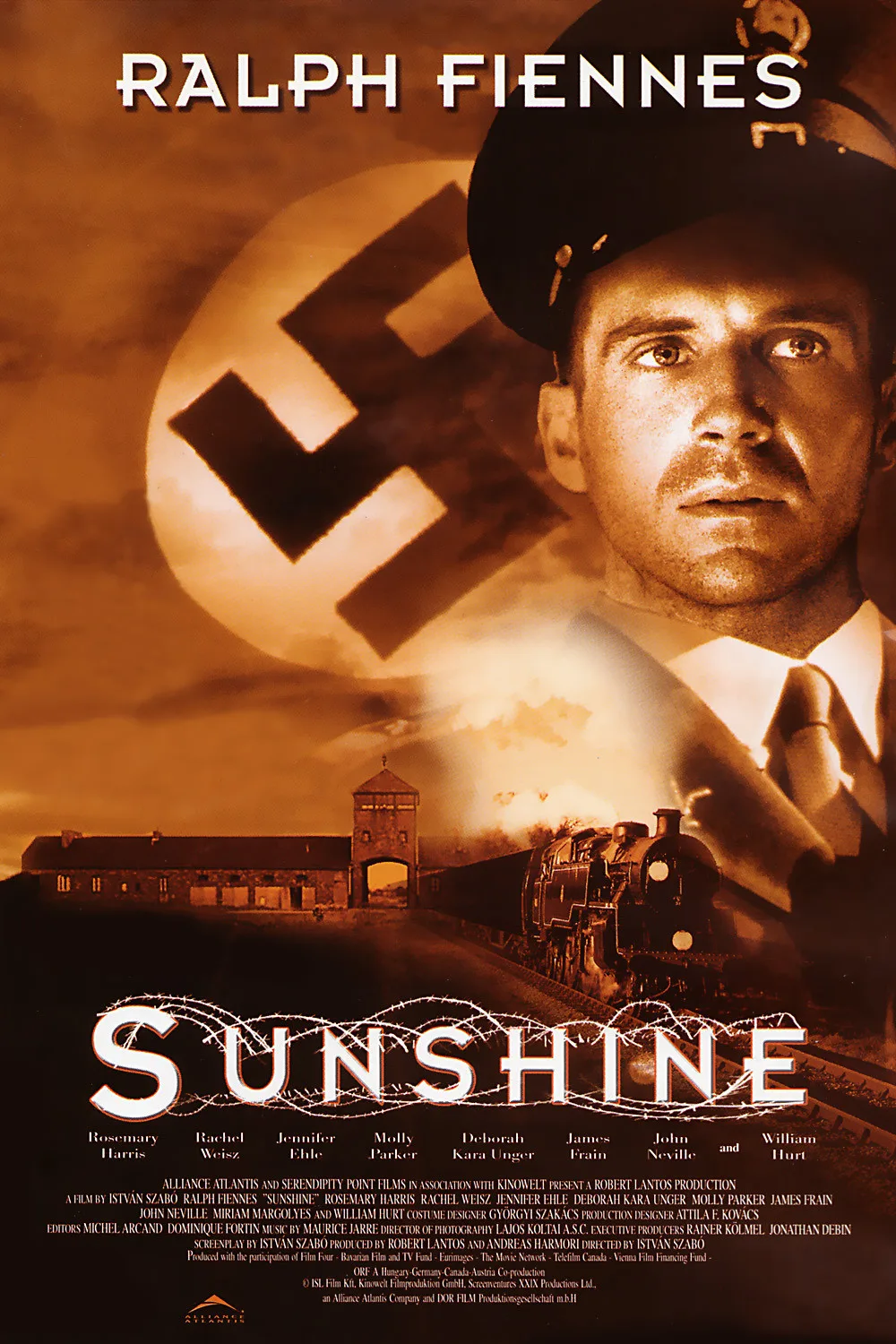

Ralph Fiennes plays the father, son and grandson, each one rebuffed or repelled by a Hungary in agony. Ignatz Sonnenschein, whose story begins the film (with some flashbacks about his father), is a successful businessman who presides over a comfortable bourgeois home and thinks of standing for parliament. His brother Gustav (James Frain, and later John Neville) is disgusted he would support a corrupt regime, and Ignatz speaks hopefully of progressive elements in the regime, and the emperor’s openness to reform.

After the war, a communist government gets in briefly, and Gustav joins it. Then the rise of the right ends that chapter, and he is placed under house arrest before fleeing to France. Meanwhile, Fiennes now plays Adam Sors, whose attention is focused on fencing; since the best fencers are in the officers’ club, he takes lessons and converts to Catholicism so he can join it, too. He doesn’t take religion seriously; it’s just a ticket you punch in order to fence.

His son Ivan (Fiennes again–uncanny in his ability to suggest the three different personalities) emerges after a war as a police officer under the new communist regime. Ivan grows close to an idealist named Knorr (William Hurt), who believes in communism and wants to do a good job, and so therefore is a threat to the government. This sequence, showing a weary Hungary being betrayed once again by a corrupt regime, is the most effective, because it pounds the message home: The people running the communist government are more of the nice ordinary Hungarians who helped with the Holocaust. The point isn’t that Hungarians are any worse than anyone else–but that, alas, human nature is much the same everywhere, and more generous with lackeys than heroes.

At three hours “Sunshine” made some audience members restless when it premiered at the Toronto Film Festival, but this is a movie of substance and thrilling historical sweep, and its three hours allow Szabo to show the family’s destiny forming and shifting under pressure. At every moment there is a choice between ethics and expediency; at no moment is the choice clear or easy. Many Holocaust stories (like “Jakob the Liar”) dramatize the tragedy as a simple case of good and evil. And so it was, but that lesson is obvious. The buried message of “Sunshine” is more complex.

It suggests, first, that some Jews were slow to scent the danger because they were seduced into thinking their personal status gave them immunity (so do we all). Second, that those who felt communism was the answer to fascism did not understand how all “isms” distrust democracy and appeal to bullies. Third, that the Holocaust is being mirrored today all over the world, as groups hate and murder each other on the basis of religion, color and nationality. The Sonnenschein family learned these lessons generation after generation during the century. So did we all. Not that human nature seems to have learned much as a result. Is there any reason to think fewer people will die in the 21st century than died in the 20th, because they belong to a different tribe?