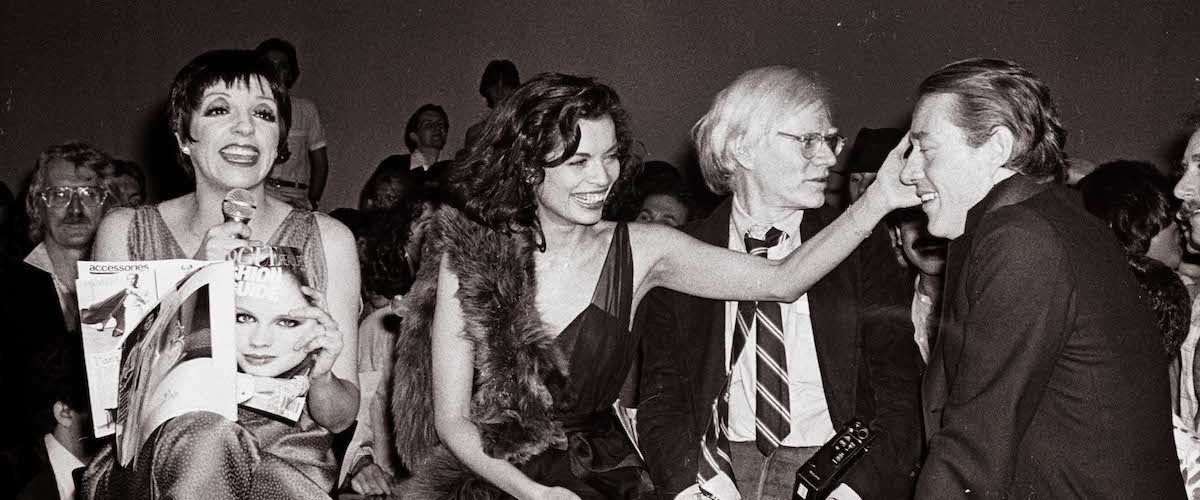

I am old enough to remember the heyday of Studio 54. It was covered by the New York City media on an almost daily basis. Something was always happening there and it usually involved somebody famous. It was the place to be seen, a glamor pit of decadence that appeared to be Heaven and Hell existing in the same location. Back then, I was way too young to go, which was probably for the best; Matt Tyrnauer’s documentary “Studio 54” tells us that gaining entry was damn near impossible. My 19-year-old cousin once managed to finesse her way inside, and she told me that she accidentally tripped over Liza Minnelli. What Liza was doing on the floor remains an unsolved mystery, though I am sure she was having more fun than I’ll ever experience in my life.

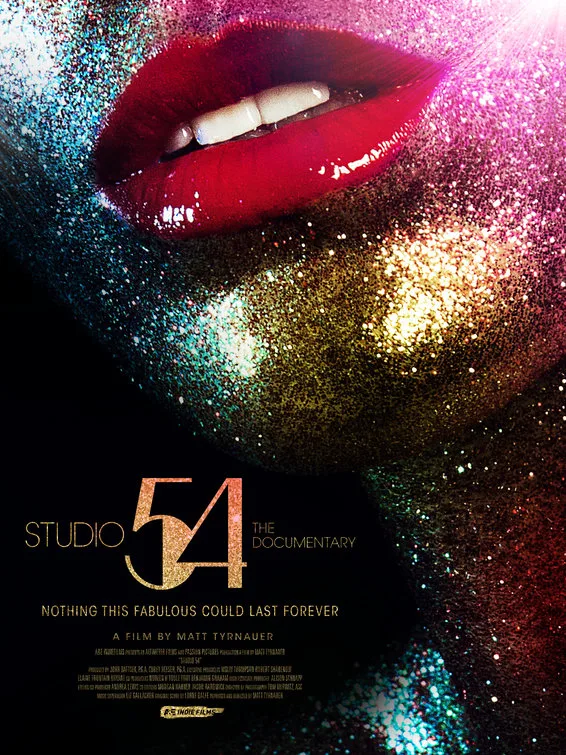

My unhealthy obsession with Studio 54 wasn’t sated with Mark Christopher’s 1998 fictional feature “54” because its plot had been butchered into a dull respectability by Miramax. Unfortunately, “Studio 54” has a similarly unsatisfying problem—it feels a bit too tame. The club created by Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager deserves something as decadent as a night in there must have been. Something tells me that had Rubell still been around to interview (he died in 1989), he would have brought the party, the gossip and done all manner of talking out of school. Instead, we’re left with his business partner and best buddy Schrager, whom more than one talking head in this documentary points out was the quieter one of this duo.

Schrager owns a series of hotels worldwide now, so while he’s willing to give us a first-person account of what went down, you always feel he’s downplaying some of the saucier aspects. There’s a sense of him trying to respectfully lean away from the insanity—with good reason I suppose—as the Studio 54 shenanigans eventually sent him and Rubell to jail. As a result, our tour guide is overshadowed by other supporting players who either appear in old footage or cross Tyrnauer’s viewfinder. We hear from the set designer, business partners and even Mark Benecke, the doorman responsible for keeping most of New York City outside of the building. There are a few celebrity appearances, the most memorable is by Michael Jackson. Appearing in his “Off the Wall”-era guise, Jackson seems almost too innocent to be extoling the virtues of a club where people had sex in its balcony.

That balcony was originally part of the Gallo Opera House, which opened on the West side of New York City in 1927. Before falling into disrepair, the building became a television studio for CBS. When Rubell and Schrager bought it, many of the remnants of its former CBS life were still present. Set designer Richie Williamson took advantage of these show-biz elements, putting in fancy, polyester-melting lighting, adding massive sound systems and keeping the theater’s stage. Studio 54 was designed to mimic an extrovert’s wet dream; to be there was to perform for, and with, the crowd. People felt they could be themselves, we are told. Some of the regulars included a guy who was a Wall Street banker by day and a famous drag queen by night, and a really randy old lady who was played in Christopher’s fictional retelling by Ellen Dow, the rapping granny from “The Wedding Singer.”

“Studio 54” is at its best when detailing the history of the New York City clubbing scene. The film talks about prior clubs like Enchanted Gardens, and how disco’s origins were the product of queer and brown people. It also reminds us that the club’s location was in a place you had to be out of your damn mind to go to at night. Being in Hell’s Kitchen after hours in the 1970’s was like wearing a neon sign that said “please rob me and beat my ass.” But when the club opened on April 26, 1977, the crowds were enormous and completely without fear. The media helped stoke the flames of popularity by running an almost endless stream of pictures and gossip items from the club.

The money came pouring in, which of course got the attention of the Internal Revenue Service. OF the club’s financial success, Rubell said “only the Mafia does better.” The IRS took that as a troll, and on December 14, 1978, they raided Studio 54. This was the beginning of the club’s downfall, which “Studio 54” studiously and effectively documents. My problem, however, is that more time is devoted to the downfall than the good times, a cinematic proportion that’s as American as apple pie: Ten minutes of fun must always be followed by thirty minutes of punishment. And yet, “Studio 54” almost redeems itself with Schrager’s neat summation of the club’s heyday. “It was fun holding on to a lightning bolt,” he tells us. This film needed a few more strikes of that lightning.