The movie is by Steve James, who directed the great documentary “Hoop Dreams” (1994). For years, people asked him, “Whatever happened to those kids?”–to the two young basketball players he followed from eighth grade to adulthood. James must often have wondered about the kid nobody ever asked about, Stevie. While he was a student at Southern Illinois University, Steve was a Big Brother to Stevie, but he lost touch in 1985, after graduating. Ten years later, he went back Downstate, to the town of Pomona, 10 or 15 miles down the road from Carbondale, to seek out Stevie.

That must have taken some courage, and even on his first return James must have suspected that this story would not have a happy ending. But it has so much truth, as it shows an unhappy childhood reaching out through the years and smacking down its adult survivor.

Here are a few facts, for orientation. Stevie Fielding was not wanted. He was born out of wedlock, does not know who his father is, was raised by a mother who didn’t want him, was beaten by her. When she did marry, she turned him over to her new husband’s mother to raise. He also made a circuit of foster homes and juvenile centers, where he was raped and beaten regularly.

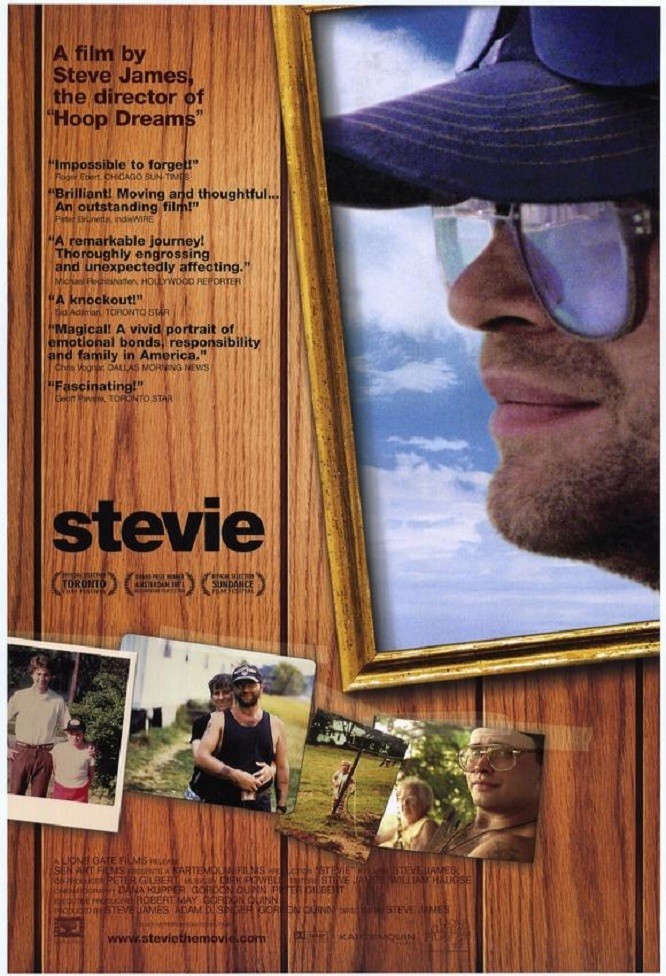

When we meet Stevie again, he is 23 and not doing well. His tattoos and Harley T-shirt express a bravado he does not possess, and he makes a poor impression with haystack hair, oversize thick glasses and bad teeth. The most important person in his life is his girlfriend, Tonya Gregory, who on first impression seems slow, but who on longer acquaintance reveals herself as smart about Stevie and loyal to him. His stepsister Brenda is also a support, a surrogate mother who seems the best-adjusted member of his family, perhaps because, as her husband tells us, “they didn’t beat her.” Stevie freely expressed hatred for his mother, Bernice (“Some day I am going to kill her”), and she is one of the villains of the piece, but having stopped drinking, she feels remorse and even blames herself, to a degree, for Stevie’s problems–especially the latest one. Between 1995, when James first revisits Stevie, and 1997, when production proper started on this documentary, Stevie was charged with molesting an 8-year-old girl.

Stevie says he is innocent. Even Tonya thinks he is guilty. We do not forgive him this crime because of his tragic childhood, but it helps us understand it–even predict it, or something like it. And as he goes through the court system, Tonya stands by him, Brenda helps him as much as she can and Bernice, his mother, seems slowly to change for the better–to move in the direction she might have taken if it had not been for her own troubles.

There is no sentimentality in “Stevie,” no escape, no release. “The film does not come to a satisfying ending,” writes the critic David Poland. He wanted more of a “lift,” and so, I suppose, did I–and James. But although “Hoop Dreams” ended in a way that a novelist could not have improved upon, “Stevie” seems destined to end the way it does, and is the more courageous and powerful for it. A satisfying ending would have been a lie. Most of us are blessed with happy families. Around us are others, nursing deep hurts and guilts and secrets–punished as children for the crime of being unable to fight back.

To watch “Stevie” is to wonder if anything could have been done to change the course of this history. James’ big-brothering was well-intentioned, and his wife, a social worker, believes in help from outside. But this extended family seems to form a matrix of pain and abuse that goes around and around in each generation, and mercilessly down through time to the next. To be born into the family is to have a good chance of being doomed, and Brenda’s survival is partly because she got out fast, married young and kept her distance.

Philip Larkin could have been thinking of this family in his most famous poem, whose opening line cannot be quoted here, but which ends: Man hands on misery to man. It deepens like a coastal shelf. Get out as early as you can, And don’t have any kids yourself. Search the Web using the first two lines, and you will find a poem that Stevie Fielding might agree with.