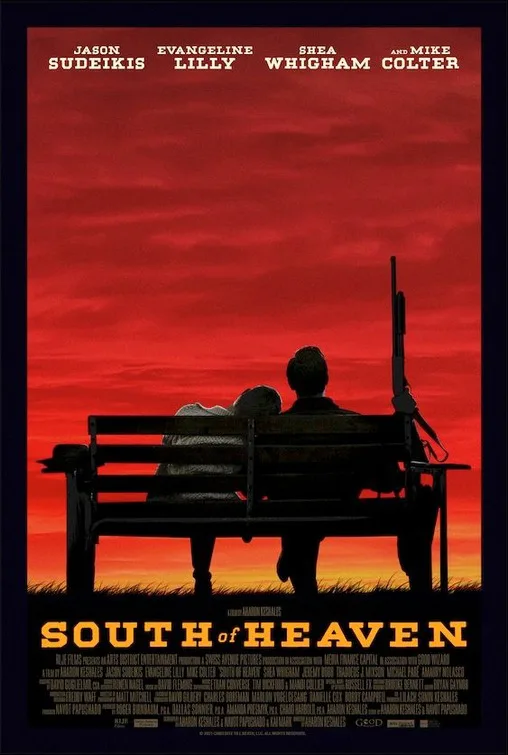

Much of “South of Heaven”‘s plot feels like microwaved leftovers, even though there are good performances, and some interesting scenes where expectations are upended (a welcome change compared to the rest). But nothing coheres, and not much helps it stand out from its long line of predecessors, “Straight Time” perhaps being the most obvious example. When a criminal re-enters society after time behind bars, it is difficult—sometimes impossible—to avoid getting sucked back into the old life. Even if the ex-con wants to go “straight,” the temptation is irresistible and old habits die hard. Written and directed by Aharon Keshales, whose debut (2010’s “Rabies”) was an attention-getting nail-biter, “South of Heaven”—with a couple of exceptions—is inert and unimaginative.

Jason Sudeikis plays Jimmy, serving out a prison sentence for armed robbery. “South of Heaven” opens with Jimmy’s to-the-camera plea for early release so he can marry his girlfriend Annie, who has lung cancer and less than a year to live. Jimmy’s plea works, and before you know it he’s back home with Annie (Evangeline Lilly), trying to adjust to freedom, to life outside. Annie has waited faithfully for twelve years to bring him home. The honeymoon period lasts less than 24 hours.

Schmidt, Jimmy’s parole officer (Shea Whigham, in a quiet and ominous performance), sets him up with a day job, while Frank (Jeremy Bobb), Jimmy’s old partner-in-crime, tries to entice Jimmy into illegal activities, just like the old days. Schmidt keeps showing up, hovering on the periphery of Jimmy and Annie’s bowling date, showing up at Jimmy’s place of work. He blackmails Jimmy into accepting a sleazy side gig, delivering a bag to a bunch of drug dealers, a seemingly simple “get in and get out” job. Of course it all goes south. It goes even further south when Jimmy, frazzled, driving too fast, hits a guy on a motorcycle, killing him. It was an accident, but Jimmy panics and ropes Frank in to help him “disappear” the situation. However, by an outrageous coincidence, the guy who was killed was a courier for the local drug kingpin, and he apparently had a suitcase filled with money on him. The drug kingpin wants it, and comes after Jimmy to get it.

Mike Colter plays Price, the drug kingpin, in what is the most effective performance in the film. He’s soft-spoken and reasonable, although surrounded by violent “strong men” (one of whom is played by Michael Paré). He makes his way inexorably, through Frank, and then Annie, to get to his target. He just wants his money back, that’s all, and he’s convinced Jimmy has it.

Keshales films much of this in a predictable style, where conversations play out in dueling medium-shots, back and forth and back and forth. That style can work well when used sparingly (like Dennis Hopper and Christopher Walken’s scene in “True Romance“), but when used in every scene, the conversations seem to occur in an airless vacuum. There’s nothing in the space between the characters, there’s no connection established, and no room for those little bits of human behavior that can fill in so many blanks. Keshales uses these dueling medium shots in scenes between Jimmy and Annie, too, which impose distance on the relationship. They don’t seem to be in the same geographical location. If this is a deliberate choice, to highlight Jimmy’s distance from real life, it doesn’t work. It also makes the film seem sparsely populated. Jimmy and Annie have no friends, no family, nothing outside their relationship. They don’t seem to exist in the larger world.

Keshales shakes things up visually in a couple of sequences, and (not surprisingly) these are the best in the film. One is a series of shots showing the wind rising: trees wave, curtains flutter, banners ripple, wind chimes clank around alarmingly. It’s very eerie, suggesting the calm before the storm. The other standout sequence is a shoot-out involving multiple people that takes place in one location. It’s all done in seemingly one shot, the camera gliding around corners and moving down hallways, with men popping out from everywhere, stand-offs occurring every few seconds. A sequence like this requires a ton of planning and coordination and it pays off.

Sudeikis is a gifted actor. He keeps things simple, but he can go big and exaggerated if necessary. He was lovely in “Colossal,” “Kodachrome,” “Tumbledown,” “Sleeping With Other People,” and he’s excellent in “Ted Lasso,” a perfectly plausible everyman, not afraid to show unlikable qualities. He doesn’t push and he doesn’t indicate, and he’s very good here.

Evangeline Lilly as Annie doesn’t fare as well. Part of this is because of the character’s conception. Annie is wrapped in a golden glow of acceptance and humor—like all cancer patients are in unimaginative movies. Lung cancer is a horrific way to die. Anyone who has witnessed someone die of lung cancer knows what it does to the body. Annie shows no signs of the disease. She doesn’t have to catch her breath or slow down. She has energy to keep doing the things she loves. At one point, she runs really fast, showing no signs of being winded. Her hair is short, and Lilly keeps fiddling with it, making it seem more like a chic new haircut, as opposed to the result of chemotherapy. Annie is the epitome of Cancer as Plot Point, one of my least favorite cinematic tropes. It’s hard to invest emotionally in a trope masquerading as a human being.

The film has its pleasures, but they come only in the moments where the unexpected happens (a scene between Price and Annie is a standout). “South of Heaven” is mostly like its title: lukewarm, generic, and safe.

Now playing in theaters and available on digital platforms.