Charles Lane‘s new film, “Sidewalk Stories,” is a silent movie shot in black and white. If you are absolutely sure you wouldn’t want to see a silent, B & W movie, read no further. There is no help for you here.

What I want to evoke is the different consciousness created by watching a silent film. Sitting in the dark, viewing “Sidewalk Stories,” I became aware that somehow my attention had been heightened and I was looking at the screen with more intensity than would usually be the case. Why was this? I think perhaps the silent format inspires us to participate more directly in the movie. A sound film comes to us, approaches us – indeed, it sometimes assaults us from the screen. But a silent film stays up there on the glowing wall, and we rise up to meet it. We take our imagination and join it with the imagination of the filmmaker.

That’s what happened to me during “Sidewalk Stories.” Another interesting thing also happened. Watching this movie photographed in New York City in 1989, I found myself being set free from a lot of my stereotypes and preconceptions about the big city by the fact that the film was silent. In a sound film, the characters usually represent themselves. In a silent film, they represent a type. They stand for others like themselves, which is one reason silent films are more universal than talkies.

In sound movies set in modern cities, for example, we are likely to assume that street people are violent, disturbed and anti-social. “Sidewalk Stories” opens with a long, elaborate tracking shot past a row of sidewalk entertainers – jugglers, pavement artists, magicians, three-card-monte shills – and because the film is silent, we do not assume that they are all clones of Travis Bickle. They seem like gentler, more universal characters, like people we would meet in a film by Chaplin. That’s a strange assumption, since the movie is set in an area of present day Greenwich Village where drug dealers and other vermin are always present, and yet the silent film somehow mythologizes the characters.

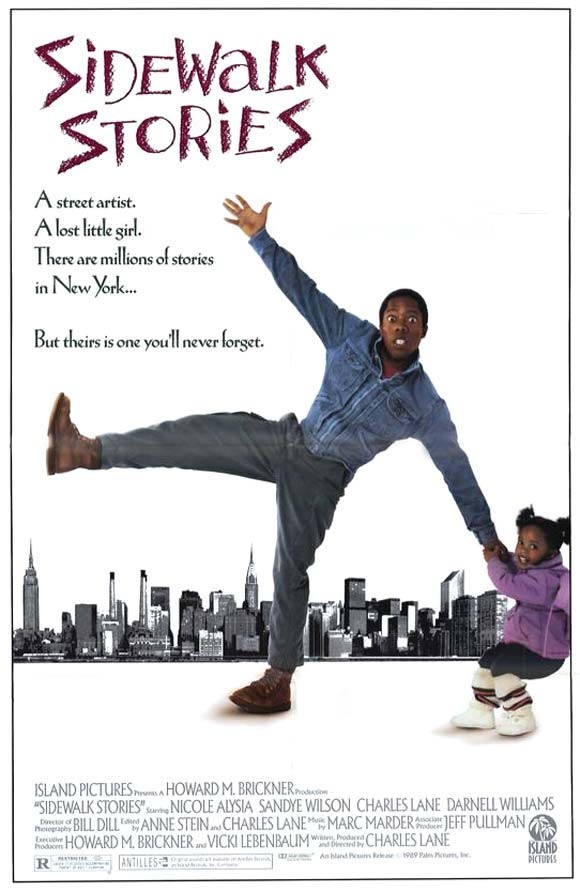

The shot ends on a shot of the Artist (played by Charles Lane). He is a small, determined black man who has set up his easel and hopes to convince pedestrians to pay him to draw them. Right next to his spot on the pavement is another artist, a tall, broad bully who also wants this turf. He pushes the Artist to the ground. The Artist gets up. He pushes him over again. The Artist gets up again. He pushes him over a third time. He begins to get up, thinks better of it, and pushes himself back down to the ground – saving the bully trouble.

This is, almost movement for movement, a comic bit of business from Charlie Chaplin. It’s as if Lane is starting his film by acknowledging that debt. Then he moves on. As the story develops, the Artist befriends the mother of a small girl, and after an altercation in an alley involving the mother and the girl’s father, the Artist finds to his consternation that he has been left with the little girl and it’s up to him to protect her.

In a sound movie, he would go to a social agency. In a silent movie, of course, he takes her home with him – home to the rude little room where he is a squatter in the ruins of a church marked for demolition. And he begins to figure out how to care for the little orphan. (The child is played perfectly by Lane’s daughter, Nicole Alysia, and her naturalness is one of the strengths of the movie.) The domestic details, right down to the box of Corn Flakes, all provide comic possibilities. And when it turns out that the child’s crayon scrawls are snapped up as “modern art,” the movie takes a wicked turn.

The movie’s story develops as a melodrama, in which the Artist is befriended by a successful businesswoman (Sandye Wilson), threatened by thugs, and eventually is able to restore the child to her rightful mother (Trula Hoosier). Along the way, there are the kinds of confrontations between rich and poor that Chaplin liked to explore, including a scene where the businesswoman invites the Artist and the child to her apartment, but the doorman doesn’t want to let them in.

Lane is endlessly inventive in the ways he finds to create humorous situations and tell his story through images, and the soundtrack music, by Marc Marder, reinforces everything that happens. The movie, at 97 minutes, seems shorter.

I have a quarrel with one thing Lane does. At the end of the film, the camera lingers in a public place where some of the homeless have congregated. They’re panhandlers, asking the passing public for change, and gradually, slowly, we begin to be able to hear their voices on the soundtrack: “Remember the homeless!” “Can you spare a quarter?” The sound in this sequence was not necessary. Lane’s whole movie has already made the points that he now reinforces with spoken dialogue. It violates the magic of silence. But up until then, “Sidewalk Stories” weaves a spell as powerful as it is entertaining.