Moment after moment, scene after scene, “Secrets & Lies” unfolds with the fascination of eavesdropping. We are waiting to see what these people will do next, caught up in the fear and the hope that they will bring the whole fragile network of their lives crashing down in ruin. When they prevail–when common sense and good hearts win over lies and secrets–we feel almost as relieved as if it had happened to ourselves.

Mike Leigh‘s best films work like that. He finds a rhythm of life–not “real life,” but real life as fashioned and shaped by all the art and skill his actors can bring to it–and slips into it, so that we are not particularly aware we’re watching a film; he has a scene here, set at a backyard barbecue, that shows exactly how family gatherings are sometimes a process of tiptoeing through minefields. One wrong word, and the repressed resentments of decades will blow up in everyone’s face.

It would be easy, but wrong, to describe the plot of “Secrets & Lies” as being about an adopted black woman in London who seeks out her natural birth mother, discovers the woman is white, and arranges to meet her. That would be wrong because it sidesteps the real subject of the film, which is that the mother and her family have been all but destroyed by secrets and lies. The young black woman is the catalyst to change that situation, yes, but her life was fine before the action starts and will continue on an even keel afterward.

Given the deep waters it dives into, “Secrets & Lies” is a good deal funnier and more entertaining than we have any right to expect. It begins with the black woman, a thirtyish optometrist with the quintessentially British name of Hortense Cumberbatch (played by Marianne Jean-Baptiste). After the death of her adoptive mother, she goes to an adoption agency to discover the name of her birth mother, and thinks there must have been a mistake, since the papers indicate her mother was white. There was no mistake.

We meet the mother, named Cynthia, who is played as a fearful, nervous wreck by Brenda Blethyn (who won the best actress award at Cannes for this performance). She lives in an untidy council house with her daughter Roxanne (Claire Rushbrook), who works as a street sweeper, is in a foul mood most of the time, and has a boyfriend whom she has thoroughly cowed. Cynthia mourns the fact that her beloved younger brother Maurice (Timothy Spall) hasn’t called her in more than two years, and blames Maurice’s wife Monica (Phyllis Logan), that “toffee-nosed cow,” for the long silence.

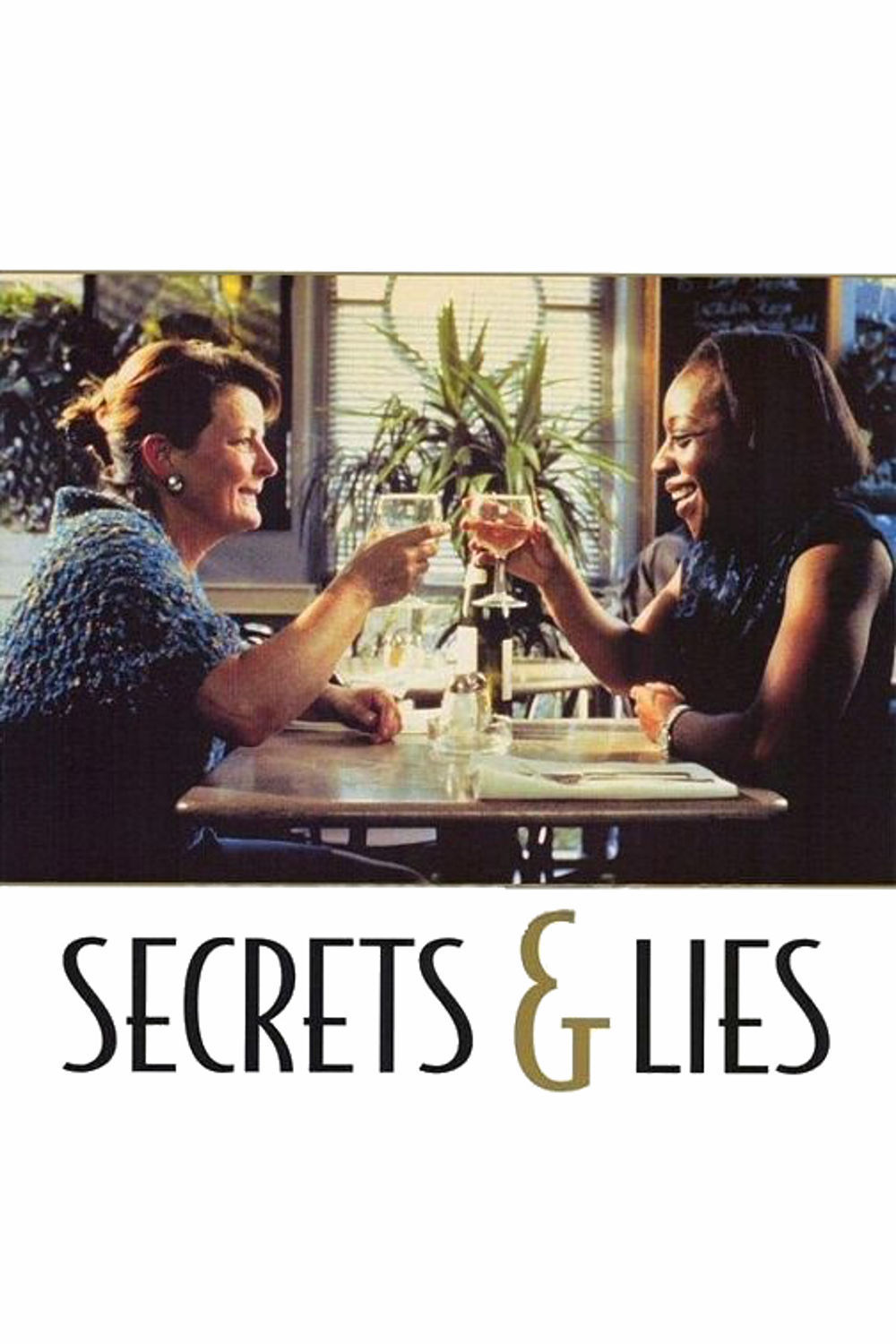

The phone rings. It is Hortense. “Oh, no, no, no, no, no, dear–there’s been some mistake!” says Cynthia. But Hortense persists. Cynthia hangs up. The phone rings again, and she approaches it like an animal sure the trap is set to spring. But she agrees to meet Hortense, and the scene of their meeting–outside a tube station and then in a nearby cafe–is one of the great sequences in all of Mike Leigh’s work, based on incredulity, disbelief, memory, embarrassment and acceptance. “But you can’t be my daughter, dearie!” Cynthia exclaims. “I mean . . . just look at you!” She claims she has never even slept with a black man, and she is telling the truth, but then a moment comes when she arrives at a startling revelation, and we don’t know whether to smile or hold our breaths.

Much of the film is devoted to the domestic life of Maurice and Monica. He is a photographer specializing in wedding pictures; she is a loving woman whose life becomes unbearable for herself and her husband every 28 days. Spall, whom you may remember as the proprietor of the doomed French restaurant in Leigh’s “Life Is Sweet,” is a born conciliator, wanting to make everyone happy and usually failing.

The movie arrives at its magnificent conclusion at the family reunion, the barbecue where Cynthia brings Hortense and introduces her as a “friend from work.” Soon the family is trying to puzzle out why an eye doctor would be employed at a cardboard box factory. Leigh and his actors (who develop the characters and dialogue together, in collaboration) play this scene in one unbroken take, in which six characters eat, drink, talk, and stumble across secrets and lies.

I have admired the work of Mike Leigh ever since 1972, when his “Bleak Moments” premiered in the Chicago Film Festival. For many years he was an outcast from British cinema; it’s hard to get financing when you don’t have a script or even the idea for a film, but Leigh stubbornly persisted in his method of gathering actors and working with them to create the story. In the 1970s and 1980s, he worked mostly in London theater and for the BBC, and then came “High Hopes” (1988), “Life Is Sweet”, “Secrets and Lies,” which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, is a flowering of his technique. It moves us on a human level, it keeps us guessing during scenes as unpredictable as life (the visit, for example, of the former owner of the photography studio), and it shows us how ordinary people have a chance of somehow coping with their problems, which are rather ordinary, too.

One intriguing aspect of the film is the way Leigh handles race: The daughter is black, the mother is white, the family has no idea Cynthia had another child, and yet race is not really on anybody’s mind in this film. They think they have more important things to worry about, and they’re right.