With so many forms of escapist distraction vying for our attention at any given moment, how does a serious, muckraking documentary go about holding the interest of more than just its target demographic? The most common solution filmmakers have chosen is to structure their narratives like a popcorn thriller, conveying the urgency of their subject matter through quick cuts and bracing music cues. Though some examples of this approach have resulted in great cinematic works, such as James Marsh’s “Man on Wire,” many directors end up undermining the vitality of their subject matter by preventing its various outrages from resonating on their own terms. The extent to which a documentary’s style comes off as a contrivance equals the degree to which it risks losing the faith of its audience.

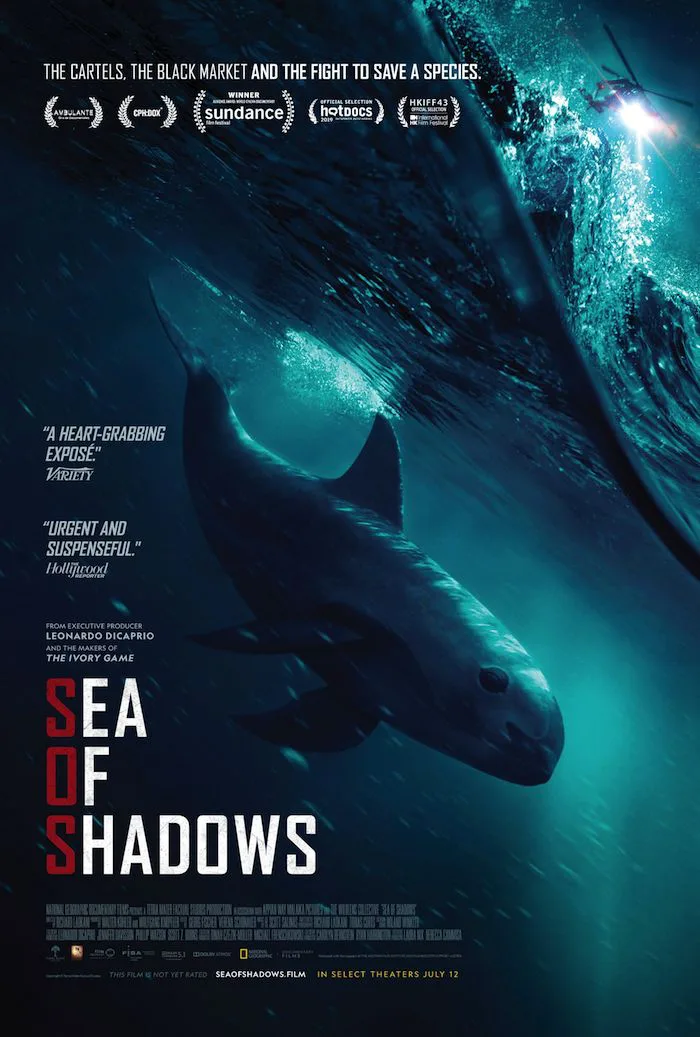

Richard Ladkani’s “Sea of Shadows” appears to have connected with viewers, as evidenced by the Audience Award it garnered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, yet to my eyes, its opening moments did not hold much promise. The pre-title sequence featuring a confrontation between illegal fishermen and the heroic marine conservation vessel Sea Shepherd reeks of such manufactured unease that it could’ve been pulled from any peril-at-sea blockbuster. The fact that the film never quite circles back to this particular event makes it even more of an anomaly. Then we are presented with a series of title cards, laying out the premise in PowerPoint-style bullet points that are the very antithesis of cinematic language. What they tell us is inherently alarming, yet it’s a shame that such crimes aren’t conveyed in a more visually compelling way.

For its first half or so, Ladkani’s film takes the form of an environmental PSA laced with genre tropes. The names of various locations are identified in lettering that fills the screen, while the score by H. Scott Salinas (“A Private War”) consistently intrudes upon the action, amplifying the dread during already tense moments and accompanying the platitudes expressed by interview subjects with touchy-feely melodies. What initially tugged at my heartstrings was the mere sight of the vaquita whale, the smallest of its species, endowed with a smile permanently etched on its ghostly face. In recent years, its population on earth has dwindled below thirty, as the nets of profit-minded fishermen have killed off numerous creatures living in the Sea of Cortez, a wondrous habitat dubbed by Jacques Cousteau as “the aquarium of the planet.”

We are repeatedly reminded throughout the picture that the plight of the vaquita serves as a microcosm for our own survival in the face of environmental catastrophe triggered by unchecked greed. The filmmakers and their ensemble of subjects clearly don’t care about being too on-the-nose—after all, the title’s acronym, “SOS,” is highlighted in red when it materializes onscreen. Yet considering the vaquita is teetering on the brink of extinction, the lack of humor or nuance in Ladkani’s direction is understandable. His chief goal is to shed light on the complex web of corruption that has resulted in the whale’s current race against time. What makes the metaphor linking the vaquita’s uncertain future with that of our own all the more apt is that the forces opposing both are anchored in superstition. Turns out the multimillion dollar black market destroying the whale’s last refuge is fueled by a myth, not unlike the one upheld as truth by those blinded souls eagerly awaiting armageddon.

The inexplicable MacGuffin that serves as the fishermen’s prized catch is the swim bladder of the totoaba fish, considered a delicacy in Chinese cuisine, and according to unproven ancient beliefs, contain certain medicinal powers that have caused it to be valued higher than gold. How ironic that the quest for healing remedies has directly caused irreparable damage to our ecosystem. This organ is treated by Mexican cartels like any other drug served to Chinese traffickers, leading it to be appropriately dubbed “the cocaine of the sea.” What’s most enraging in this type of all-too-common crisis are those members of the working class who are manipulated into actively working against their own well-being, branding the findings of whistleblowers as lies and thereby enabling criminals to evade justice. Not only are the fishermen along the Sea of Cortez desperate to protect their livelihood, they are also scared into submission by an insidious cartel and its alleged hitman, Oscar Parra, who are all too happy to take advantage of their victims’ willingness to bend the rules.

By refusing to comply with governmental orders to cease using totoaba nets, referred to by the Sea Shepherd’s first mate, Jack Hutton, as “walls of death,” these fishermen will soon find themselves with nothing left to fish. Continuing their family’s legacy of fishing that has been passed down from one generation to the next, Javier and Alan Valverde go the legal route by assisting in the removal of nets, thus allowing a target to be placed on their backs whenever entering the water. Yet even these brave men are pressured into moving south in order to avoid any conflict with Parra and his cronies. There’s no question that the blood of the soldier killed on camera by Parra is on the hands of every law enforcement official indebted to the cartel. “Sea of Shadows” is one of those breathless exposés that seems as paranoid as its subjects, where every unidentified drone and bystander brandishing a phone could be deemed a potential threat. When a revelation is unearthed, it is often uttered by a pixelated face with a voice distorted to sound like it belongs to André the Giant.

So often does the film flip back and forth between its multiple story threads—encompassing everything from investigative journalists tracking down the cartels to marine veterinarians aiming to rescue vaquitas before they vanish—that I kept wishing Ladkani would’ve simply selected one narrative and followed it for maximum impact. As the film progressed, however, I began to admire how all sides of the story were, at the very least, being illustrated in a way that was thorough and digestible, creating a comprehensive look at the problem, though falling short of a transcendent one. This is the latest eco-conscious doc executive produced by Leonardo DiCaprio, who has used his celebrity platform much like Televisa reporter Carlos Loret de Mola does here, to sound the warning bell for disasters that could be avoided, provided we care enough to halt them in their tracks. Since “Sea of Shadows” is being distributed by National Geographic, its sequences of breathtaking underwater photography are expected and do not disappoint, though the imagery that lingers most vividly in my mind occurs in harsh daylight, as we survey the miraculous specimens robbed of life in the name of financial gain.

When my cousin Jeremy Scahill made “Dirty Wars,” an Oscar-nominated documentary also framed like a thriller, he had misgivings about being placed frequently on camera while serving as the film’s narrator. It was imperative for him, as an investigative journalist, to ensure that his story never upstaged those of his subjects. In many ways, he’s a kindred spirit of Andrea Crosta, the executive director of Earth League International, who likens his unmasking of totoaba bladder traffickers to waging a “highly symbolic war” on our impending extinction. Perhaps Ladkani’s avoidance in allowing one story to dominate the narrative was his way of ensuring that no human presence is prioritized above the endangered vaquita, and it’s in his film’s second half that this approach pays off remarkably well. After nearly an hour of set-up, we observe how the well-intentioned efforts of Ladkani’s subjects result in one wrenching failure after another. The single most powerful moment is followed by a prolonged silence that enables us to feel the weight of the loss, as Vaquita CPR program manager Cynthia Smith discovers that her beloved marine mammal is unequipped to survive in captivity.

This tragedy is juxtaposed with those involving the Sea Shepherd’s sole weapon of airborne surveillance to scare off poachers and an embarrassing clash between naval forces and disgruntled fishermen determined to free their guilty peers from prison, effectively driving home why the trafficking must stop immediately. “Sea of Shadows” is a worthy successor to Ladkani and Crosta’s 2016 Netflix documentary on illegal trading, “The Ivory Game,” though I strongly recommend that viewers also seek out the 30-minute doc, “Souls of the Vermilion Sea,” currently streamable on Vimeo. It was helmed two years ago by Ladkani’s co-directors, Sean Bogle and Matthew Podolsky, and provides considerably more context to the Valverde family history, the vaquita’s distinctive traits and the illegal fishermen’s lethal cocktail of debt and denial. Taken together, these films paint an engrossing portrait of mankind’s encroaching, self-inflicted demise, with moneyed interests leading us, like the pied piper, off the cliff and into the sea.