“Scrooged” is one of the most disquieting, unsettling films to come along in quite some time. It was obviously intended as a comedy, but there is little comic about it, and indeed the movie’s overriding emotions seem to be pain and anger. This entire production seems to be in dire need of visits from the ghosts of Christmas.

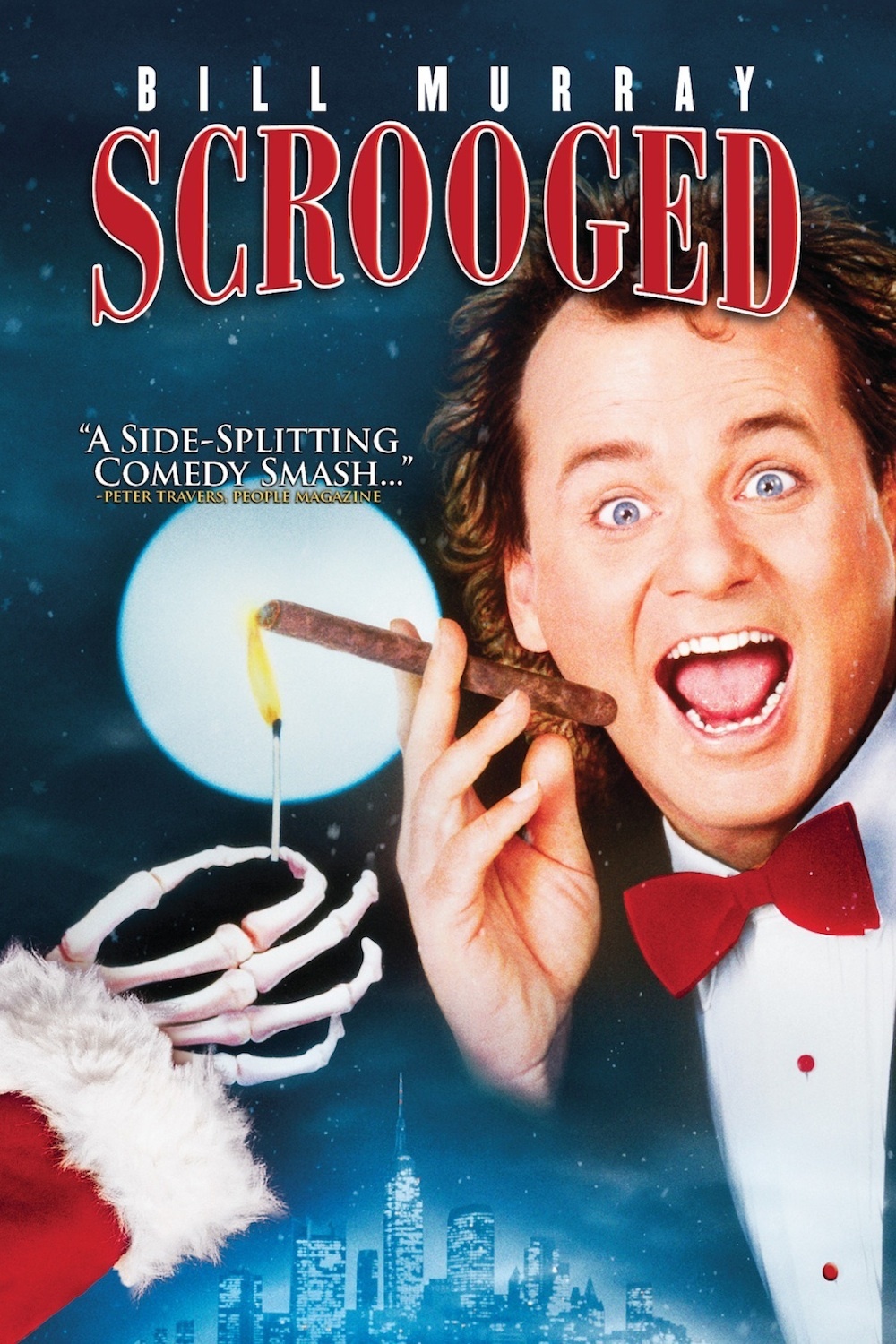

The movie stars Bill Murray as Frank Cross, a tormented TV network president who is approaching the Christmas season in a foul mood. He has cut himself off from everybody who loves him, he delights in criticizing and humiliating his colleagues, and he leads a lonely life, sitting in his high-rise office, watching TV and pouring down the vodka. His idea of an effective promotional ad is one that scares viewers into watching. His next production will be a live, multimillion-dollar Christmas Eve performance of “Scrooge,” and we follow him through the wreckage of his life as he attempts to wreck the TV show, as well.

Cross is a thoroughly miserable wretch, played by Murray in a thoroughly miserable mood. What seems to be missing are the lightness and good cheer that lurk beneath the surface of most Murray performances. He’s often gruff in his movies, but in a way that lets you know he’s just kidding. This time, he doesn’t seem to be kidding.

Murray’s ill humor affects the chemistry of scene after scene, introducing a kind of undertow. When he shouts at people, he doesn’t add a little spin of self-mocking exaggeration, so that we know to laugh. He seems to be really shouting. And the other actors look as if they really feel shouted at.

During the course of “Scrooged,” the TV executive experiences his own version of the events that haunted Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Cross is visited by the ghosts of Christmas past, present and future, and shown how miserable he really is, and how unhappy he has made everyone else.

The Bob Cratchit of his story is his long-suffering secretary, Grace Cooley (Alfre Woodard). Her son, the Tiny Tim character, is old enough to speak, but has never opened his mouth. Cross gives the secretary a bath towel for Christmas, but when he is taken by a ghost to look in through the window of her household, he realizes how much happiness is missing from his life.

Meanwhile, there is trouble for Cross on the professional front. The chief executive officer of the network (Robert Mitchum) has lost confidence in him, and brought in a brash outsider (John Glover) to “lend a hand.” Cross fears that his job is threatened, especially since the Mitchum character seems to have gone off the deep end. (“Do you realize,” the CEO asks his underling, “that there is increasing evidence that dogs and cats watch television?”) The fear of job loss and the lessons from the Christmas ghosts result in a moral transformation for Cross, and in the final scenes the repentant TV executive barges onto the set of the live production of “Scrooge” and testifies to his change of heart.

This sequence is the strangest in the film. The words are there, but the heart is lacking. Murray stands center stage and rants and raves about the spirit of Christmas, but it’s not an inspiring speech and certainly not a funny one. It sounds more desperate than anything else, and it continues at embarrassing length. It looks like an on-screen breakdown.

Finally, he demands a miracle, and his secretary’s little tyke is dragged forward to demonstrate that he can actually speak at last. Then the entire cast and crew line up behind Murray to sing of Christmas cheer, and I can’t remember when I’ve seen anything along these lines that was more forced and depressing.

What went wrong here? I have no idea. The chemistry must have been bad from the start. Or perhaps the material was simply intractable. One problem is that Murray frequently interjects one-liners that are at right-angles to the material, blocking the flow of the story. He gives the impression, at those moments, that he is seeking to distance himself from the film, but a story like this works only if it seems to believe in itself.

You can’t bad-mouth “A Christmas Carol” all the way through and then expect us to believe the good cheer at the end. In his studies of Dickens in preparation for this role, Murray seems to have read only as far as “Bah! Humbug!”