There is a brunch scene in “Scenes from the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills” that illustrates many of the ways in which the movie goes wrong. A former soap opera star (Jacqueline Bissett) is being interviewed by a magazine reporter in the presence of many of her friends and neighbors, and the conversation alternates between the banal (“There are 17 separate fires burning at this very minute”) and the rude (“Peter, why don’t you tell your new wife that you’re in love with Clare?”).

It is true that much of the conversation in Beverly Hills, and elsewhere, concerns the weather and natural phenomenon, and that shocking truths can sometimes explode in the center of a brunch conversation. But as you listen to the speeches in the scene, which continues for some time, you realize that it is all simply dialogue.

No real attempt has been made to create consistent characters and then allow them to talk as they really might. “Scenes from the Class Struggle,” etc., is an assortment of put-downs, one-liners and bitchy insults, assigned almost at random to the movie’s characters.

The film was directed by Paul Bartel, who specializes in comedies about unspeakable behavior (his biggest hit was “Eating Raoul,” about cannibalism). He likes to shock, but I am not sure I would agree with him about what is really shocking. I am shocked when people do something unexpected, bizarre and out of character, but I am not shocked – especially in the movies – when people say and do things simply to be shocking. Their behavior then becomes predictable, and boorish.

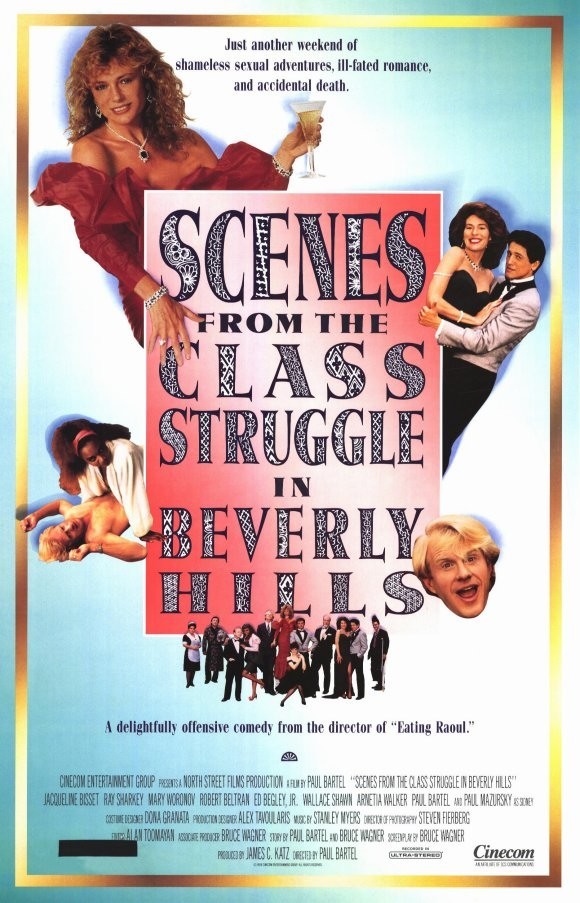

The movie, an original screenplay by Bruce Wagner, tells the story of two affluent Beverly Hills wives (Bisset and Mary Woronov), who live side by side and share many things, including friends and perhaps lovers. Bisset’s husband, Sidney (Paul Mazursky), has died in kinky circumstances shortly before the movie opens, but his ghost visits her from time to time, still bitter. Woronov is in the middle of a disintegrating marriage with a pipsqueak (Wallace Shawn), and both women become the subject of an interesting bet by their house servants (Ray Sharkey and Robert Beltran): They wager $5,000 on who can seduce the other’s employer first.

The sex scenes are the best ones in the movie, not because of the sex (where Bartel and Wagner could have actually been more satirical) but because of the dialogue leading up to, and away from, the sexual encounters. This dialogue at least sounds and feels as if it has been generated by the moment. The rest of the dialogue in the movie sounds arch, contrived and written, and most of the time we don’t believe that the characters would really be saying it (example: “Ride me . . . ride your sad little private pony straight down into hell!”).

The ghostly husband, played by Mazursky, inspires distractions that are not helpful to the movie. For one thing, we are reminded that Mazursky directed “Down and Out in Beverly Hills,” a considerably funnier movie about the same terrain. For another, we’re reminded of Noel Coward’s “Blithe Spirit,” about another marriage and another ghost, and of how Coward, for all of his addiction to epigrams and witticisms, made the characters work as people. “Scenes from the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills” sounds more like an anthology of punch lines from famous anecdotes about the rich and the boring.