All Stephen Ward ever really wanted to do in life was to move in the right circles, with the right friends, and be left in peace and quiet. His strategy for gaining admission to the world of British society was unorthodox, but not unkind. He found young women with promise but no prospects, and then he groomed them, coached them, took them to the right places and introduced them to his important friends.

He was, in a sense, the Henry Higgins of his time, and his most successful Eliza Doolittle was a poor but pretty girl he discovered in a strip show. Her name was Christine Keeler, and he lovingly transformed her into a desirable companion for cabinet members, diplomats and the aristocracy. His only miscalculation was to allow her to sleep with the British defense minister and a Russian military attache during the same period. That was a mistake that brought down a government, and cost Ward his life.

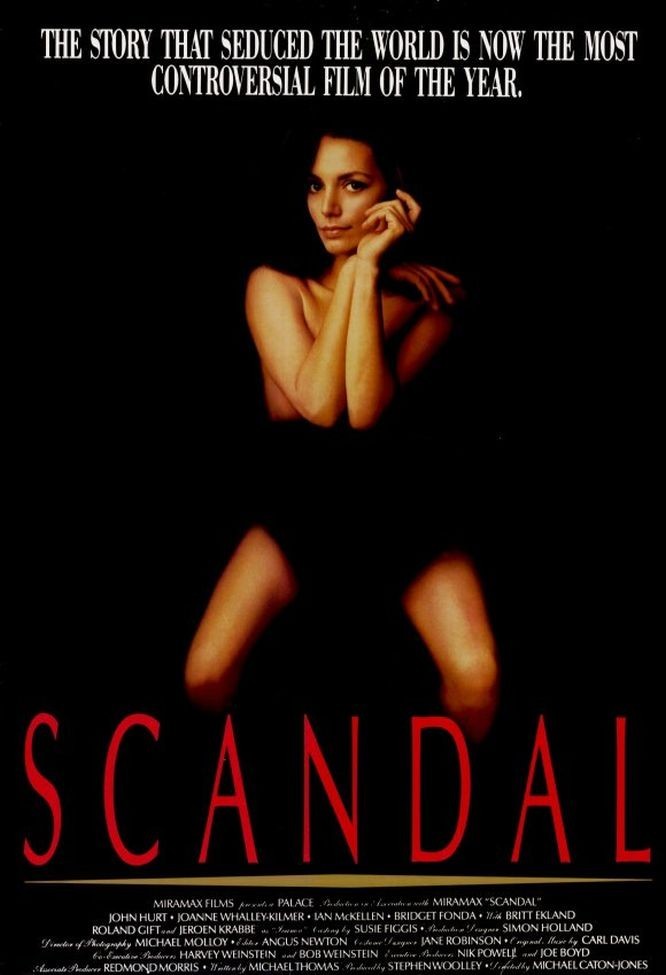

“Scandal” tells the story of Stephen Ward with a great deal of sympathy for his motives, and a great deal of anger against the British establishment. Although Ward was convicted of living off the earnings of a prostitute – a decision handed down after he committed suicide in the middle of his trial – the film argues that he never accepted any meaningful sums of money from anybody, and his only real motive, a rather touching one, was to do a favor for both the girls and his famous friends. If his method for doing that – arranging illicit sexual relationships – was unconventional or unsavory, let it be noted that none of the participants on either side of the bargain made the slightest complaint until they found their faces on the front pages of the newspapers.

The facts of the Ward affair are part of modern British history.

Keeler and her friend, Mandy Rice-Davies, moved in circles that included some of the most famous and powerful men of their time. After one of them, Defense Minister John Profumo, admitted that he had lied to Parliament about his involvement with Keeler, he was forced to resign, and eventually the widening scandal brought down the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan. The movie “Scandal” argues that a scapegoat had to be found to contain the outrage – and Ward, a harmless and gentle osteopath, was the victim. So efficiently and ruthlessly did the establishment circle its wagons to defend itself that even now, 25 years later, attempts to make “Scandal” as a TV mini-series were blocked in England. It has finally appeared as a movie – as a political melodrama that is also an unexpectedly touching love story between almost the only two major players who never slept with one another: Ward and Keeler.

The movie’s strength is that it is surprisingly wise about the complexities of the human heart. Although the newspapers scorned Keeler’s claim that she and Ward were simply “close friends,” the movie argues that that was quite possible, and true. She felt gratitude for his decision to pluck her from obscurity and groom her for a kind of stardom, and she believed, if she did not fully understand, that his only reward was in seeing his creation pass, respected and unquestioned, in the highest circles. Since England is one of the most class-conscious nations on earth, this sort of transfer in social strata has a powerful hold on the national imagination (remember for example the Ascot scene in “My Fair Lady,” with Eliza testing her upper-class accent).

The movie stars John Hurt in one of the best performances of his career as Ward, the chain-smoking, shabbily genteel doctor, who lives in a coach house with Keeler but spends his weekends as the guests of such friends as Lord Astor, who gave him the key to a guest cottage on his estate. In an early scene, Hurt’s eyes light up as he sees a pretty girl walking down the street, and somehow Hurt is able to make us understand that he feels, not lust, but simply a deep and genuine appreciation for how wonderful a pretty girl can look on a fine spring day.

Keeler is played by Joanne Whalley-Kilmer, an actress previously unknown to me, and she walks a fine line with great confidence, seeming neither innocent nor sluttish, but more of a smart, ambitious and essentially honest young woman who finds that it is no more unpleasant to sleep with rich and important men than with her obscure boyfriend.

Mandy Rice-Davies (Bridget Fonda) is a different type of woman, more calculating and probably more intelligent, and perhaps it is no accident that Rice-Davies has gone on to a certain success in business and society during the last 25 years, while Keeler has returned to the anonymity from which Ward tried to rescue her.

Some of the most evocative scenes in the movie involve backstage moments between the two women, when they casually discuss their lovers, plan their lives and pay the most painstaking attention to their faces.

These women apply themselves more voluptuously to their makeup than to any of the men in their lives.

The movie, written by Michael Thomas and directed by Michael Caton-Jones, has the feeling of having been made from the inside. It moves effortlessly through the minefields of British government and society, capturing such nuances as the way in which Lord Astor summons Ward to his club to inform him, shame-facedly, that the scandal has forced him to ask for the return of the key to his cottage. Always circling outside the walls of this inner sanctum are the rabble of the British gutter press. And even as a fellow newspaperman, I am willing to describe them in that way, because there is a certain level of decency in news-gathering that they seem never to have glimpsed.

“Scandal” is a sad story about human nature, which understands why people sometimes sleep in the wrong beds and takes note that this is understood privately, but not publicly. When the light of day shines on these affairs, lives are destroyed. The saddest moment in the movie comes in the final courtroom scene, when Keeler is called as a witness and is mercilessly battered by the prosecutor until finally Ward stands up in the defendant’s box and cries out, “That is not fair!” That is the cry of this movie.