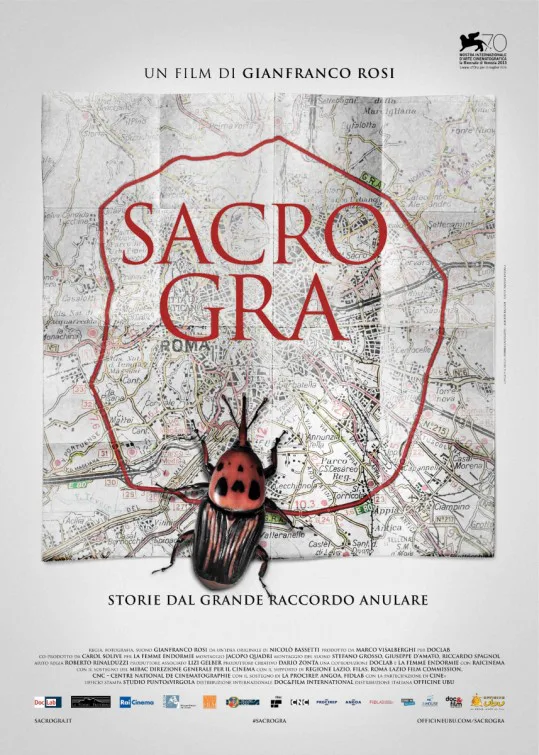

Gianfranco Rosi’s documentary “Sacro GRA,” the first nonfiction film to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, is a slice-of-life movie that portrays Romans who live near the 42.5-mile long highway that loops around the city. It’s the sort of film that would seem to cry out for interpretation, or at least for an answer to the question, “What is the point of this?” It’s a mosaic-style film that strings together brief character sketches and striking tableaux, and then periodically returns to key characters and settings as the movie unfolds, creating a rhythm that will prove either mesmerizing or boring, depending on whether you like the film (or are willing to give yourself over to it; I’d argue that the second condition determines the first, though admittedly I’m getting ahead of myself here).

The film’s people, or “characters,” include an eel fisherman who has long, comfortable conversations with his wife at their dinner table and sometimes grouses about the media and the international fishing conglomerates threatening his livelihood; an older man (perhaps a professor but maybe a cheese-maker, though I was never entirely sure about what he does) who lives with his teenage daughter and launches into amiable but rather involved monologues; a royal who rents out his family’s lavish home for film shoots; a scientist trying to figure out how to stop beetles from chewing through a grove of palm trees near a stretch of freeway; there are a couple of prostitutes who live in a trailer, a couple of paramedics making their rounds, and so on. Sometimes we get to see individual characters in isolation (one of the paramedics becomes the de facto star of the movie) but more often we see them function as part of a couple or a work partnership. The movie has no narration or onscreen titles. There is nothing that comes right out and tells us why we’re seeing these people and situations, in this order.

Of course this opaque, diffuse, at times random-seeming arrangement of elements invites us to try to discern a pattern or superimpose one on the movie, the better to determine what kind of statement, or statements, it is trying to make. Quite a few of my colleagues have tried to do exactly that, and in so doing, have judged the movie to be sincere and often striking yet fundamentally lacking in—well, stuff. A sense of design or purpose. A reason for being, perhaps.

Maybe they’re right, but I don’t particularly care to argue about this aspect of “Sacro GRA.” I was moved by the film, not because it seemed to be trying to make a statement about contemporary Rome, or Italy, or the Western world, or globalization, or class struggle, or anything else that lends itself to a think piece or a thesis paper, but because it seemed (to me, anyway) blithely unaware of, or deliberately disinterested in, being that sort of movie.

I’d situate “Sacro GRA” at the nexus of three minor but vital subgenres of movie (or television program). One is the “beating heart of the city” film, exemplified by such diverse scripted movies as “Open City” and “New York Stories” and the documentaries “Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis” and Frederick Wiseman’s “Belfast, Maine” and “Jackson Heights”; these films are more about images and moments than propulsive, linear storytelling. Their pleasures are primarily zoological or taxonomic rather than dramatic. Any sense of structure or rhetorical agenda has to be inferred by the viewer. And you can never be entirely sure if the filmmakers really have a message or if they’re just arranging or juxtaposing bits of material (as a collage artist might) to see what happens. If somebody else saw the movie and saw a different pattern, or no pattern, you couldn’t tell them they were wrong, because the whole point of a movie like that is to project yourself onto it.

The second genre is the scripted slice-of-life movie, which has some overlap with the first category; it’s exemplified by “Do the Right Thing” (an expressionist piece of outdoor theater, confined to a single city block) and David Simon’s TV series “The Wire” and “Treme,” which had very strong documentary affinities. These kinds of city films have more shape. They feel more written, more structured. You start in one place, you go somewhere else, you visit and revisit the characters, and their stories develop along parallel lines, slowly. Sometimes the movie starts with the sun rising and ends when it sets. Other times you see the sun repeatedly rising and setting to convey a wider swath of time passing. There is a time lapse aspect to this kind of city movie. It’s as much about the textures and rhythms of city life as it is about the individual characters.

There’s a third subgenre of movie echoing through this film’s running time: the neorealist film in which a large cast of mostly nonprofessional actors “performs” fascinating but often mundane actions. “Open City” was one of the first examples of this kind of film, but we’ve seen versions of it in different countries and in different media. “The Wire” and “Treme” had a neorealist strain, and during the aesthetic peak period of Iranian cinema, the ‘80s and ‘90s, some of the greatest movies were stocked with “actors” who were more or less playing themselves.

None of this is meant to imply that anything in “Sacro GRA” feels fake. Rosi spent two-and-a-half years shooting interviews and gathering footage all around the highway and another eight months editing the material. Nevertheless, these people are definitely playing themselves, in a way, because they are just naturally characters. They were characters before the filmmakers laid eyes on them. The strongest moments have the intimacy of documentary footage captured by a diligent filmmaker who just kept hanging around and hanging around until his subjects finally forgot he was there. Rosi keeps returning to a couple of apartments in a high-rise, shooting down through an un-curtained picture window at his subjects, who not only had to give him permission to spy on them in this way but had to be properly wired for sound as well. These apartment scenes feel like bits of deadpan urban theater caught on the fly; we have a balcony seat, and we’re looking through the proscenium arches of their windows. There’s a scene near the end of the film between one of the paramedics and his aged mother that’s so sweet and essentially private that watching it, I thought that this is what it must feel like to be a ghost who can loiter unseen, watching people live their lives.

The filmmaking looks for beauty everywhere, and finds it. The play of blurry taillights on a freeway becomes large-scale abstract art. The long shots of silhouetted people talking near a sunlit window in a dark room have the richness of oil-painted portraits. Yet somehow the images rarely feel fussed-over or posed. The movie does seem scattered and incomplete at times, but whether this feels like a feature or a bug will depend on what you want from the experience. If the movie lingers in the imagination (and it has lingered in mine) it’s because Rosi and his collaborators don’t seem to have any agenda besides capturing the small but important moments in real people’s lives — the kinds of fleeting emotional transactions that movies rarely think to show us.

There are intimations of decay and regeneration in the parings of younger and older people, as well as in the images of the scientist obsessing over how to kill those infernal beetles that are eating their way through the palm trees (the audio of the bugs gnawing and tunneling sounds hideous, like sound effects from a horror flick). But in the end, the movie leaves us with a “same as it ever was” feeling. Early in “Sacro GRA” there’s a long shot of a stretch of highway near a field. After a moment, a herd of sheep enters the shot from frame-right, bleating and milling about. Here we get the sense that the city has not so much overtaken or destroyed nature as incorporated it, or that perhaps nature has incorporated the city. There’s a similar sense of overlap in the movie’s observation of different relationships, especially ones where the parties are separated by a considerable age gap but find a way to communicate or coexist. That the same film could have been made fifty years ago, and could be made again fifty years from now, testifies to both its sturdy construction and its wise decision to fixate on the basics of existence and leave the superimposition of finer meaning to the audience.