But the movie keeps making that same mistake, breaking the logic of the point of view. Adopted by a young orphan stable boy named Richard (Chase Moore), Lucky finds himself in a stable of purebreds ruled by a stallion named Caesar. Lucky wants to make friends with the stallion’s daughter Beauty, but “I was only the stable boy’s horse. I wasn’t good enough to play with his daughter.” And when Lucky’s long-missing mother turns up, Caesar attacks her, apparently in a fit of class prejudice, although you’d think a stallion would be intrigued by a new girl in town, despite her family connections.

Will the mother die from the attack? “I stayed with her all night, praying that she would survive,” Lucky tells us. Praying? I wanted the movie to forget the story and explore this breakthrough in horse theology. I am weary of debates about whether our pets will be with us in heaven, and am eager to learn if trainers will be allowed into horse heaven.

The human characters in the movie are one-dimensional cartoons, including a town boss who speaks English with an Afrikaans accent, not likely in a German colony. His son is a little Fauntleroy with a telescope, which he uses to spy on Richard and Lucky. Soon all the Europeans evacuate the town after a bombing raid, which raises the curtain on World War I. The horses are left behind, and Lucky escapes to the mountains, where he finds a hidden lake. Returning to the town, he leads the other horses there, where at last they realize their birthright, and Run Free.

Uh, huh. But there is not a twig of living vegetation in their desert hideout, and although I am assured by the movie’s press materials that there are wild horses in Namibia to this day, I doubt they could forage for long in the barren wasteland shown in this film. What do they eat? I ask because it is my responsibility: Of all the film critics reviewing this movie, I will arguably be the only one who has actually visited Swakopmund and Walvis Bay, on the Diamond Coast of the Namib Desert, and even ridden on the very train tracks to the capital, Windhoek, that the movie shows us. I am therefore acutely aware that race relations in the area in 1911 (and more recently) would scarcely have supported the friendship between Richard and Nyka (Maria Geelbooi), who plays the bushman girl who treats Lucky’s snakebite. But then a movie that fudges about which side is which in World War I is unlikely to pause for such niceties.

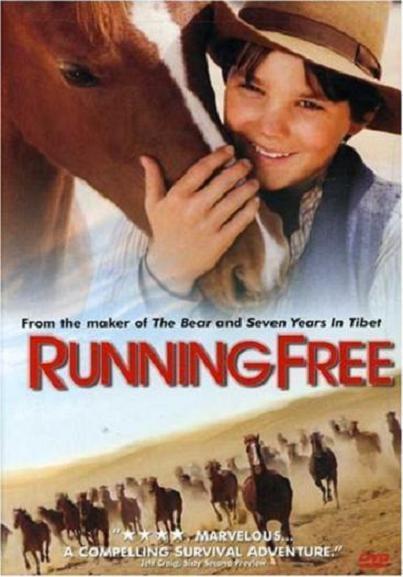

I seem to be developing a rule about talking animals: They can talk if they’re cartoons or Muppets, but not if they’re real. This movie might have been more persuasive if the boy had told the story of the horse, instead of the horse telling the story of the boy. It’s perfectly possible to make a good movie about an animal that does not speak, as Jean-Jacques Annaud, the producer of this film, proved with his 1989 film “The Bear.” I also recall “The Black Stallion” (1979) and “White Fang” (1991). Since both of those splendid movies were co-written by Jeanne Rosenberg, the author of “Running Free,” I can only guess that the talking horse was pressed upon her by executives who have no faith in the intelligence of today’s audiences. Perhaps “Running Free” would appeal to younger children who really like horses, but see my review of “The Color of Paradise,” another new release, for a glimpse of a truly inspired film for family audiences.