Jack London‘s great novel White Fang, which held me in its spell when I was 10 and again 30 years later, is the story of a dog, and the dog’s journey through many kinds of human habitations, under many kinds of masters. Much of that story can be glimpsed in this new film of “White Fang,” although not so distinctly, because the movie is the story of a boy and not a dog.

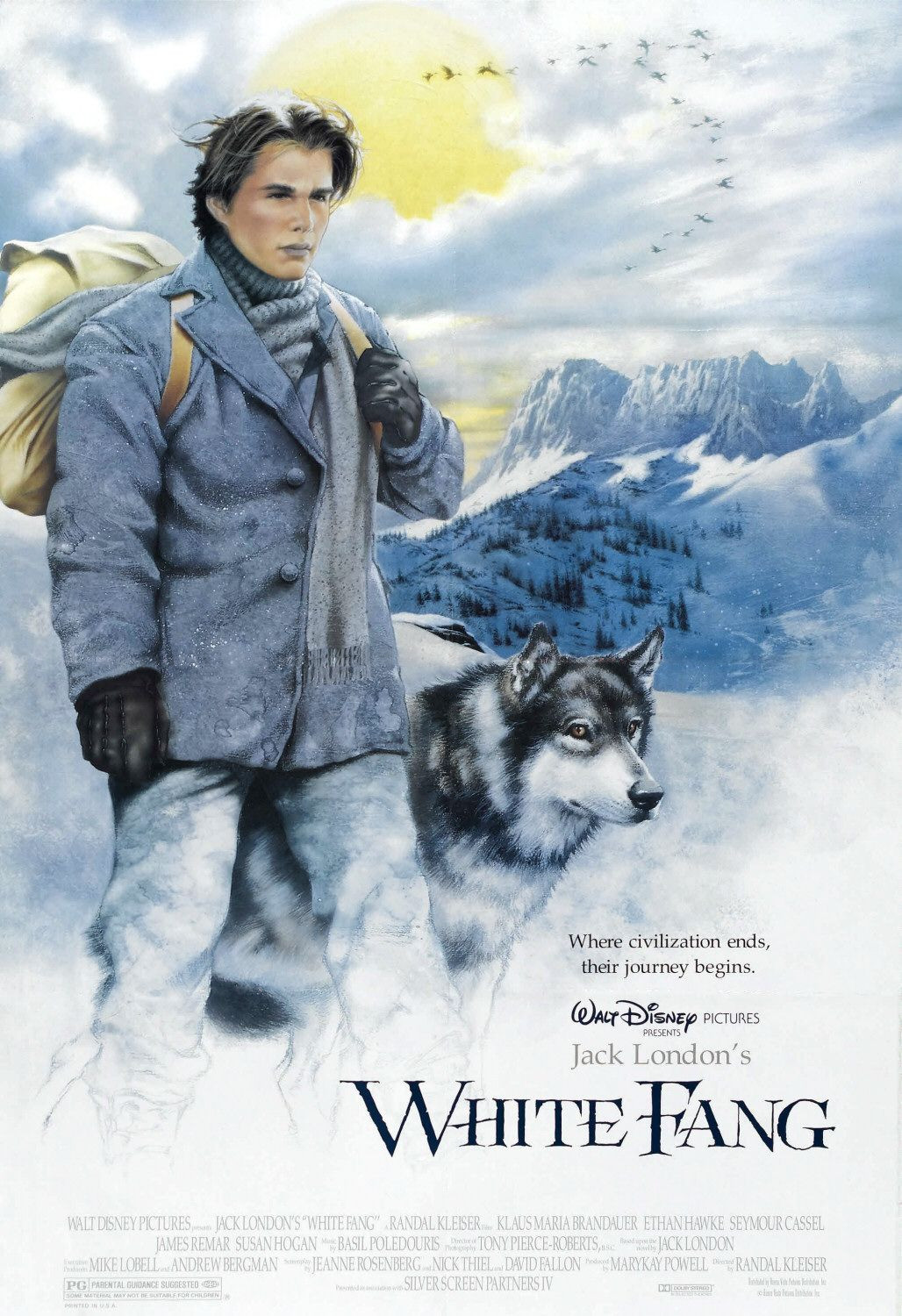

The boy’s name is Jack (Ethan Hawke), and he has come out to the Yukon in 1898 to prospect his dad’s claim in the great Gold Rush. He meets up with a couple of prospectors (Klaus Maria Brandauer and Seymour Cassel), and they travel by dogsled into the wilderness of the Arctic winter. Their adventures are intercut with the early days of White Fang, a wolf with some dog blood, whose mother is killed when he is a pup. White Fang is captured by Indians, then gets traded to men who train him for dogfights, and then finally comes into the possession of Jack, who takes him along when he goes to live at the claim.

The London novel was intended as a comparison of dogs and men, in which most men came up short. In the book the dog eventually becomes the property of a mining engineer, who takes it back to a sunny retirement in California. The Disney version of course transmutes the adult into Jack the teenager, and ends with a joyous reunion of man and beast after the human decides not to go to California after all but heed the call of the wild. Jack has good reason to stick with White Fang, who by the end of the film has saved him from being eaten by a bear and killed by thieving claim jumpers.

We are agreed then, that the movie makes no serious claim to be a version of the Jack London novel. (That project would be mostly about dogs, and require patience on the order of the 1989 film “The Bear,” which took a year to film because each of the animal movements had to be separately photographed. Fans of “The Bear” will be pleased that its star, Bart, makes a guest appearance here.) “White Fang” is, however, a superior entertainment on its own terms, a story of pluck and survival at a time when men poured into the Yukon dreaming of riches, and found mostly disease and death.

The movie is magnificently photographed on location. The performances are authentic and understated, and Brandauer makes a convincing veteran prospector, part hard-bitten, part dreamer. As the boy, Ethan Hawke is properly callow at the beginning and properly matured at the end, although it’s all he can do to carry off the final joyous reunion with the dog. And the dog itself (played by Jed) is a fine-looking, intelligent animal so good at displaying its fangs that I actually believed it could scare off a bear.

Movies like this are an antidote to the violent and defeatist thrillers a lot of younger moviegoers seem to be hooked on. It’s an adventure, it’s exciting, it stirs the imagination, and there are scenes of terrific suspense – as when Jack ventures out on that thin ice, or gets cornered by the bear. Like “The Black Stallion,” “Never Cry Wolf” and “Crusoe,” it’s a film that holds the natural world in wonder and awe. And it might even inspire someone to read the novels of Jack London, who was such a good writer he could tell a story that I fell in love with when I was 10 years old and much harder to please than I am now.