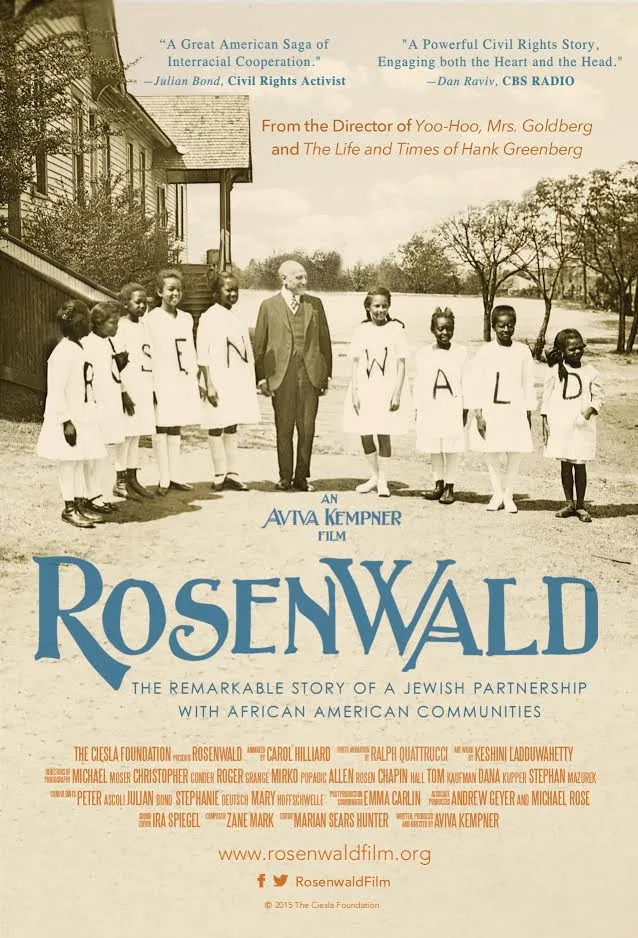

Aviva Kempner’s “Rosenwald” begins by focusing its inquisitive lens on a mystifying anomaly. Who is the white man prominently framed on the wall of numerous black schools located throughout the American South? This question turns out to be the thread that unravels a historical yarn for the ages. Most viewers will likely have little-to-no familiarity with the events recounted in this documentary, and are guaranteed to leave the theater feeling enlightened and perhaps more than a touch gobsmacked.

A majority of Windy City residents still stubbornly refer to the Willis Tower by its previous name, the Sears Tower, which remains the nation’s tallest building. Yet even that sizable tourist destination would be rendered a mere toothpick when contrasted with the towering legacy of former Sears & Roebuck CEO Julius Rosenwald. The man was many things at once: a high school dropout, a brilliant entrepreneur, a profit-driven businessman and a fiercely devoted philanthropist. He never met Abraham Lincoln, who died when Rosenwald was only 3, but his family’s house was located across the street from the President’s Springfield residence. Kempner’s film suggests that Rosenwald may be a key link between Lincoln and Obama, in how the black schools he assisted in building—which numbered over 5,300—educated the generation that preceded the civil rights movement.

As a biographer of Jewish icons unknown to many modern viewers, Kempner never gets in the way of her own material. There are no overt stylistic flourishes to distract from the strength of her story, which builds a cumulative power as it unfolds. Viewers weary of pictures deifying the hideous “white savior” trope will be pleased by how Kempner explores the bond between Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington, while illustrating that it was, in fact, their partnership that led to the creation of the “Rosenwald schools.” After reading Washington’s memoir “Up from Slavery,” coupled with William Henry Baldwin, Jr.’s “An American Citizen,” Rosenwald was reportedly motivated to aid African-Americans in their struggle against the racist barriers forged by society. He often likened the Cossacks’ attacks on Jews with the white persecution of blacks, and considered himself a “member of a despised minority.”

In an era when black people were banned from countless public spaces, and weren’t even pictured within the pages of the Sears catalogue, Rosenwald provided funding to YMCAs and housing complexes that would welcome them, albeit within segregated conditions. Though the footage of smiling tenants strolling through Rosenwald’s Michigan Avenue Garden apartments, built after the Great Migration, is presented in a positive light, the box-like shape of the structure resembles a well-manicured prison. The most joyous imagery of all occurs in the schools themselves, with their high ceilings, spacious rooms and impeccably placed windows to ensure strong natural lighting. While giving away hundreds of thousands of dollars on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, Rosenwald was encouraged by Washington to donate a portion of the money to build schools for Southern black children. The masterstroke in Rosenwald’s offer was his insistence that he would provide a third of the funding if the respective community would contribute the rest. These schools weren’t handed down from the heavens, they were built from the ground up by the very same people whose children attended them. Among their formidably accomplished alumni was Maya Angelou, who recounts in an archival interview how a child receiving A’s “would be marched from one church to another,” as the congregations beamed with pride.

Only in the film’s final third does the titular subject himself start to get lost in the shuffle, as Kempner steers her attention toward the various artists and intellectuals whose careers blossomed, thanks in part to the Rosenwald Fund. The film loses some of its focus here, yet every time it threatens to devolve into an aesthetically uninspired slideshow, another priceless bit of footage will materialize onscreen, bringing a vivid human dimension to the impact of one man’s generosity. Though it could be argued that the film will play just as well on television, some of its images will prove especially arresting when projected in theaters. Painter Jacob Lawrence’s “Great Migration” series, photographer Gordon Parks’s scathing subversion of Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” and Marian Anderson’s stirring rendition of “My Country, Tis of Thee” are all potent examples of how art can bring us closer to understanding one another, while enabling us to reclaim our identity—in this case, blacks embracing their status as American citizens.

Wholly engaging from its first frame to its last, “Rosenwald” stands as an exemplary testament to the change that can occur when wealth, power and influence are utilized for the good of humanity. It’s clear from his many accomplishments that Rosenwald had no shortage of an ego, yet he didn’t delude himself into thinking that his own needs superseded those of others. When he finally makes a brief appearance in the movie, courtesy of a filmed speech, his words resonate with more timely urgency than ever before. “Most people are of the opinion that because a man has made a fortune, his opinions on any subject are valuable,” Rosenwald replies. “Don’t be fooled…there is ample proof to the contrary.” The Koch Brothers might as well be listed as Exhibit A.