Tom Stoppard’s play “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” is the most famous modern example of a tour de force in which the action in “Hamlet” is viewed through the eyes of two of the bit players, Hamlet’s college friends, who accompany him on his trip to England. We know “Hamlet” is about Hamlet. They think it’s about Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. There’s an old joke about the actor who is hired to play the gravedigger in “Hamlet.” “What’s it about?” his wife asks. “It’s about a gravedigger who meets a prince,” he says.

As a play, “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern” is fascinating; we use our knowledge of “Hamlet” to piece together the half-glimpsed, incomplete actions of the major players, whose famous scenes we see a line or a moment at a time. As a movie, this material, freely adapted by Stoppard, is boring and endless. It lies flat on the screen, hardly stirring.

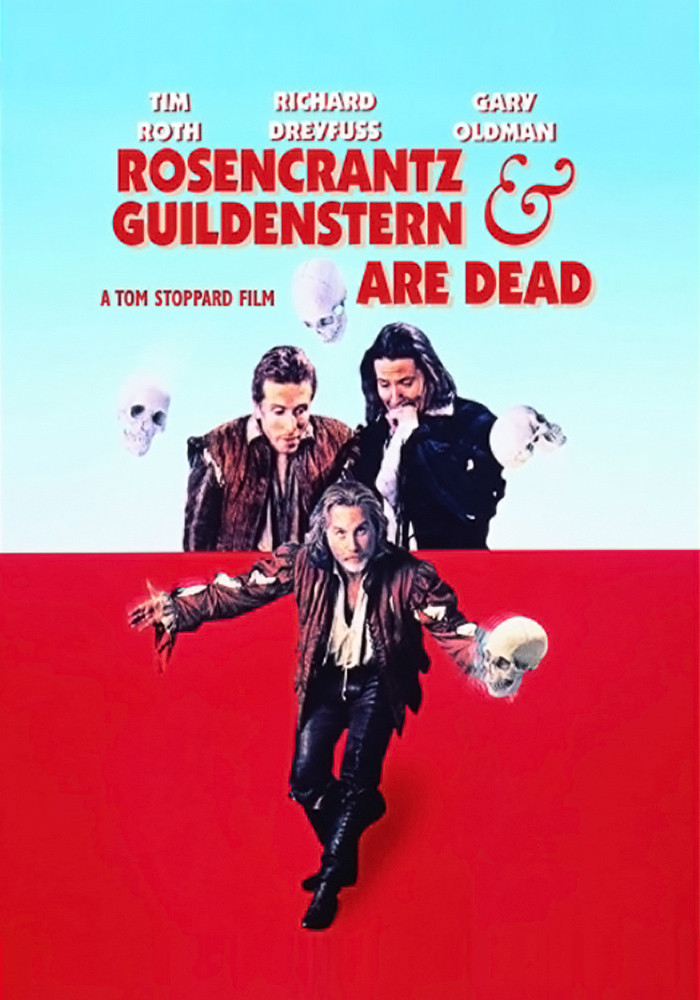

What went wrong? Since the original play is such a triumph, it is tempting to blame Stoppard in one way or another. Either his rewrite was too drastic, or his anachronistic references to future inventions are a distraction, or perhaps his camera is not confident or his cast (Gary Oldman and Tim Roth) is badly chosen.

None of those explanations will do. The rewrite would play just as successfully on the stage as the original, I suspect, and the anachronisms did not bother me, and the direction is competent and the casting defensible on the grounds that Oldman and Roth have been interesting before and will be interesting again. No, I think the problem is that this material was never meant to be a film, and can hardly work as a film.

The theatrical experience of “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern,” which I saw in London during its first run in the 1960s, was an intellectual tennis game between playwright and audience, with Shakespeare’s original text as the net. There was an audacity and freedom to the way Stoppard’s characters lurked in the wings of Shakespeare’s most perplexing tragedy, missing the point and inflating their own importance – they were the ants, without the rubber tree plant. The tension between what was center stage and what was offstage was the subject of the entire evening.

There is no offstage in the movies. The camera is a literal instrument that photographs precisely what is placed before it, and has trained us to believe that what we are looking at is what we should be looking at. Any medium that can make a star out of Mark Harmon can make heroes of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. As for Hamlet and his uncle, and Gertrude, Ophelia, Polonius, Laertes – if they’re so important, where are they? If Rosencrantz and Guildenstern were interesting characters on their own, this movie might yet survive its medium. But they are not. They are nonentities, and so intended. The most memorable performance in “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern” is the one by Richard Dreyfuss, as the leading player of the visiting troupe, and he becomes memorable in the time-honored way, by stealing his scenes.

(It is interesting that the Players, essentially dropped from the recent Zeffirelli-Mel Gibson “Hamlet,” should make their comeback in this backstage version.) The Dreyfuss scenes contain their own energy, and do not depend on the tense juxtaposition of the Stoppard foreground and the Shakespeare background.

The irony, then, is that the parts of Stoppard’s film that work best are exactly the ones that have nothing to do with the original inspiration behind “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.” To examine this irony in another way, the movie “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern” is about a troupe of players who briefly visit a story about some bit players on the outskirts of a great tragedy. Talk about opening out of town.