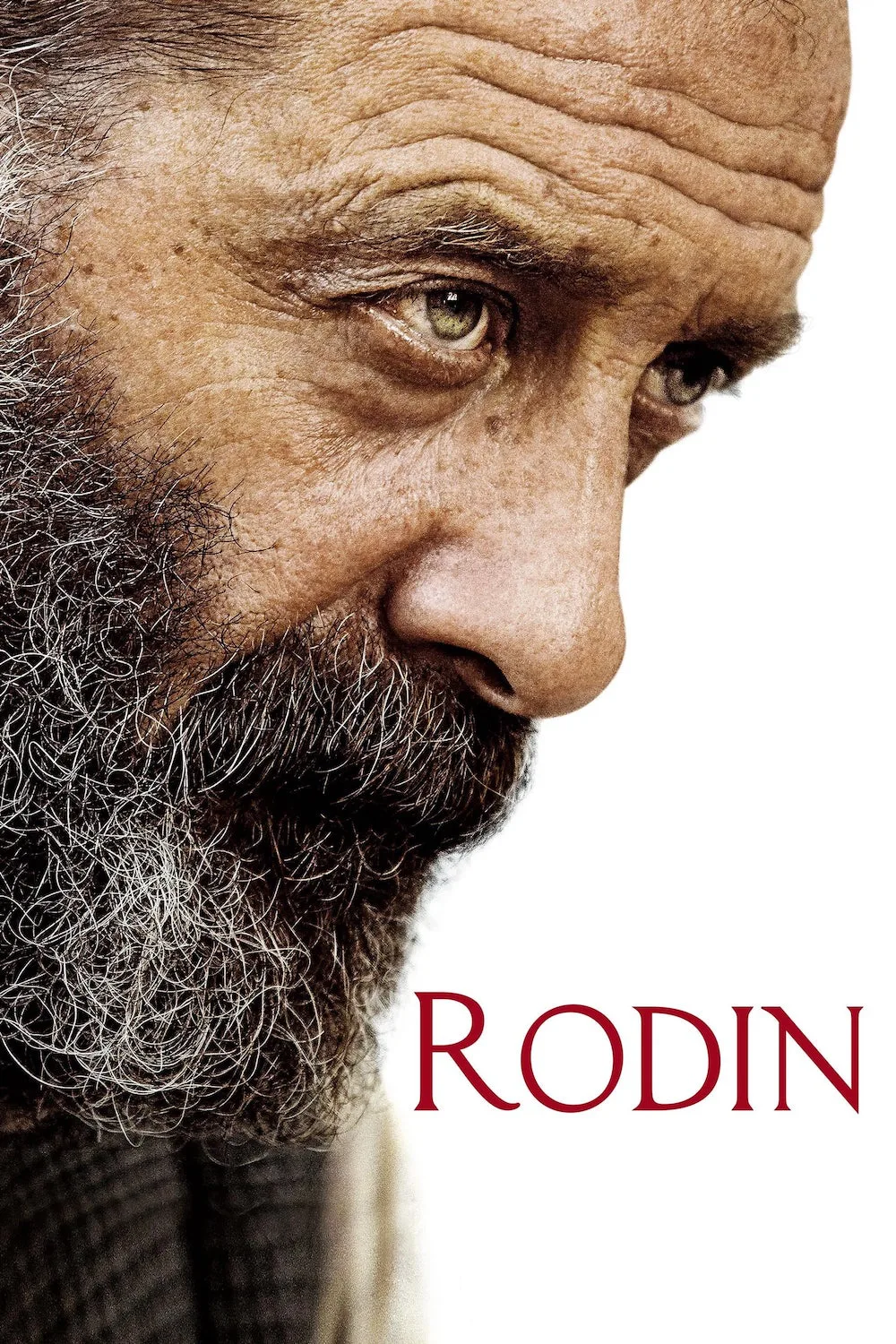

To be caught up in the world of sculpting is a special thrill that “Rodin” offers, as much as “sculpting” and “thrill” might seem like contradictory words. Writer/director Jacques Doillon achieves this by focusing on a mascot for passion of the art form, Auguste Rodin, known for starting modern sculpture. Through his intense eyes, presented with the face of Vincent Lindon, the careful shaping of stagnant figures can be vigorous, sexy, and when this movie is especially good, hypnotic.

Starting at his middle-age (and pointing out that he didn’t excel at his craft until after his 40’s), “Rodin” is no plain biopic, and it certainly doesn’t require knowledge of his work to get hooked on the film. It’s in fact best when it does away with historical details and feels like a film about an artist and their art form, who just happened to exist. Doillon’s script initially focuses on Rodin’s time crafting a piece on Dante’s Comedy, but it expands to his cameos from other famous artists: Monet, Cezanne, and Victor Hugo are just a few fellow creatives who are thrown into the mix. The story later tells of how Rodin’s sculpture of Balzac, deemed unflattering however honest, forced the sculptor to reckon with failure.

Lindon brings the same workmanlike energy that he had recently in “The Measure of a Man,” when he played a grounded, blue-collar man, who cared deeply about getting a job. But he neatly takes that gaze he brought to desperate Skype interviews to the intensity of a wild artist who thinks visually. From the start, Rodin and his other sculptors talk about the the art form as if it always involved five senses, and that they were capturing a moment of movement. It’s an exciting notion, even just to hear people talk about this stagnant art form with such passion, and Lindon vividly portrays a genius for that way of thinking.

As a narcissist who loves studying women’s bodies and making them pose, his relationship with them (all, seemingly) is chaotic. He has a life partner named Rose (Severine Caneele) who he has but discarded by the beginning to fool around with a rising young artist named Camille Claudel (Izia Higelin), thinking she will be his ultimate muse, and that her desire to marry him can be delayed. She does indeed inspire him, and they have excellent chemistry that makes this a horny movie about sculpting, but a plot thread of competitiveness arises as the apprentice threatens to beat the master. The two lovers ultimately create art that is evidence of their tumultuous passion. Rodin may initially treat her like just another muse, but Higelin, and Doillon, clearly do not.

Doillon’s filmmaking perfectly matches the passion of Rodin, like a musician biopic that feels like one of their songs. When he rushes out of one room to the next, the camera goes with him, and when he fixates on his sculpture, the gaze is still. The movie isn’t locked into his point-of-view so much as his energy, and it makes us all the more attentive that the camera is focused more on the expressions of the humans, not the famous sculptures they’re looking at.

And just as true to a film about a sculptor, Doillon continues the dedication to the practical tools of his craft, like camera framing and the placement of his actors within the frame. It’s not overly-precise but full of life, just like how the whites and grays of Rodin’s studio pop in a way such a color palette rarely does. With breathless compositions of Doillon’s own, the art forms of sculpture and film become one.

The film should almost come with an asterisk; yes, it’s all about Rodin, but Rodin as a subject is relatively incurious. On paper, he’s another macho rock star with clear talent and repetitive vices, looking for his next big hit. But this real life figure’s story isn’t singlehandedly what makes “Rodin” so enrapturing: it’s Doillon’s messy, non-precious handling as a screenwriter, and the gorgeous images he sculpts himself as a director. And it’s in the way Lindon shows a constant fire in his soul to create beauty. “Rodin” quietly defies biopic convention by showing that a great biopic does not need a great hero, so much as a vision and an immense passion.