‘I’m 22, and I still haven’t accepted that this is my life,” says Beverly Donofrio (Drew Barrymore), the heroine of “Riding in Cars With Boys.” She has a drunken and shiftless husband, a son from a teenage pregnancy, and a rundown house on a dead-end street in a section of town well known to the police. It doesn’t help that her father is the chief of police.

Her problems all started not from riding in cars with boys, but from parking in cars with boys, and getting pregnant. Her wisdom in choosing the father didn’t help. Ray Hasek (Steve Zahn) is an aimless slacker with a basically good heart, not too many smarts, and a life that’s moving way too fast for him to keep up while he’s using drugs and booze. His wife is manifestly smarter than he is, although not smart enough to avoid blaming her life on everyone but herself.

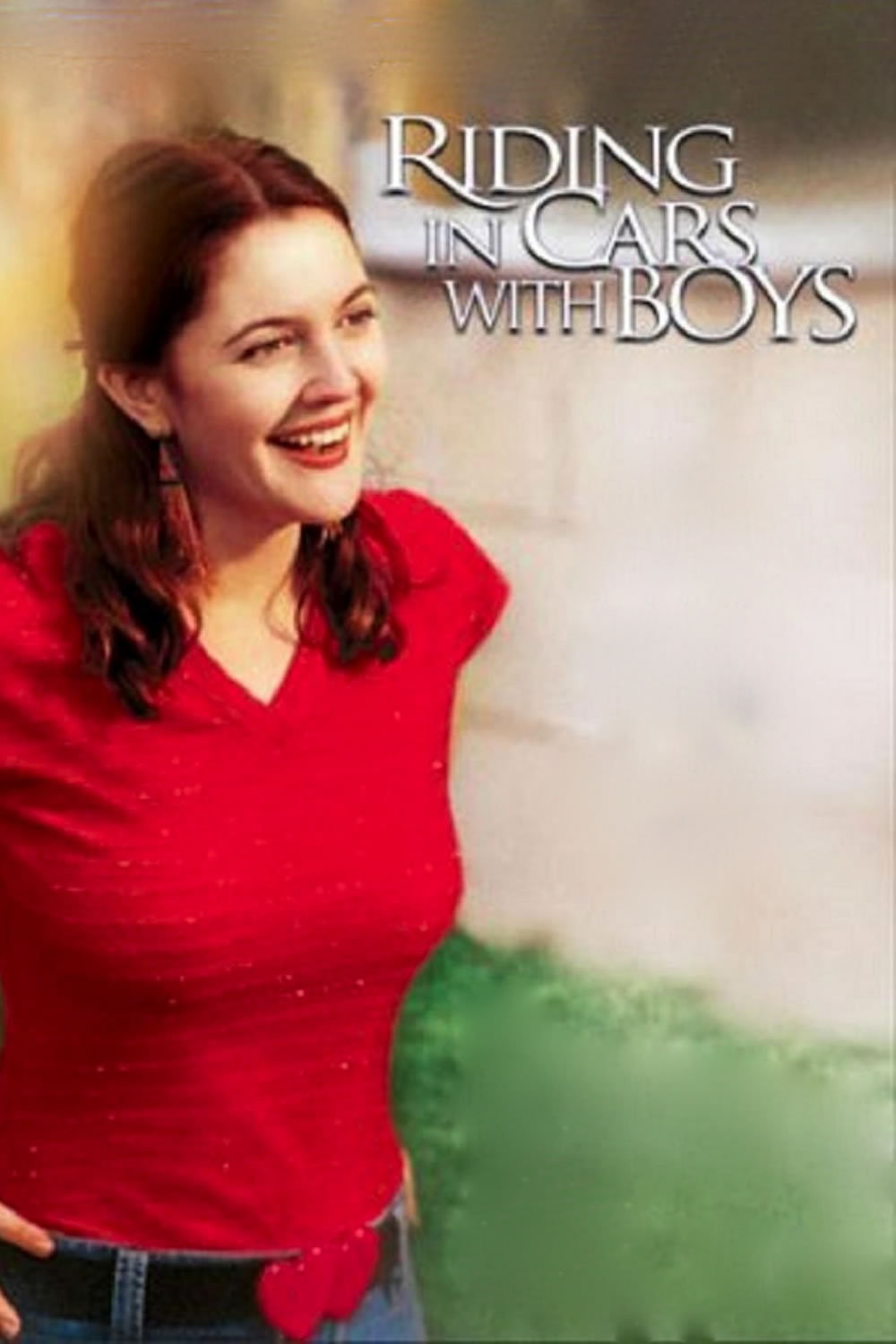

“Riding in Cars with Boys” is directed by Penny Marshall and based on a memoir by the real Beverly Donofrio (reportedly much revised by the screenwriters). It’s a brave movie, in the way it centers on a mother who gets trapped in the wrong life, doesn’t get out for a long time, takes her misery out on her son, and blames everything on her fate and bad luck. The movie traces a series of developments that dig her deeper into unhappiness.

If only she hadn’t gotten pregnant. If only the father hadn’t been Ray. If only her parents had been easier to talk to. If only … well, if only she hadn’t gone riding in cars with boys. The best way to avoid the problems of teenage pregnancy, as Beverly would be the first to tell you, is by not getting pregnant.

The movie is a showcase performance for Barrymore, who ages from 15 to 36, who doggedly plugs away trying to take classes and win college scholarships, who is heroic in her efforts to give her son, Jason, a right start in life, but whose fatal character flaw is that every time she looks at Jason she sees him as the reason for her misery. There’s a key scene where Ray is supposed to baby-sit Jason while Beverly goes for a scholarship interview. Ray forgets. She has to take the kid along, and his presence possibly costs her the scholarship. “For me,” Jason remembers later, “it’s not how Ray let her down, it’s about how my mere presence at the age of 3 crushed all of her dreams.” Zahn’s performance is crucial to the film. He has played dim bulbs before (“Joy Ride,” “Happy, Texas“), but usually for comic effect. Here he creates a character from the ground up, a dead-on accurate study of a man whose addiction to alcohol and drugs is simply too much for him to negotiate, so that he wakes up already defeated by the struggle ahead. How can you ask a man to do anything constructive when he’s already exhausted by the task of feeding his system its daily fix? That he wants to do better, that he loves his son, that he knows his wife’s resentment is justified, arouses our pity: He pays the price every second of his trembling existence for his shortcomings.

The movie opens with Jason as a young man, driving with his mother for a meeting with the father he barely remembers. She has written a book about her life, and needs his signature on a release form to protect the publishers against a lawsuit. This meeting will be one of the most painful scenes in the movie (underlined by the presence of Ray’s second wife, played by Rosie Perez as the crown of thorns to top his other sufferings).

What Jason sees clearly is that his mother is more concerned about her book than about how Jason will react to this sight of the broken, smelly, pathetic wreck who is his father. Beverly has been a dutiful mother but not a wise one. No child can carry the burden of a parent’s unhappiness, and a parent who demands that is practicing a form of abuse. Because the movie is honest enough to see that, “Riding in Cars With Boys” is brave–not the story of plucky Drew Barrymore struggling through poverty and divorce to become a best-selling author, but the story of a woman whose book, when it is published, will be small consolation.

Perhaps her unhappiness begins with her parents–the police chief (James Woods) and his wife (Lorraine Bracco). They are not bad people but, like their daughter, they are more concerned with what is “right” than with how to parent with love. And the failing goes down to the third generation, in a remarkable scene where little Jason rats on his own mother. Desperate for money, she has allowed a neighbor to dry some weed in her oven, and (1) the kid actually tells his grandfather the cop, and (2) the cop actually arrests his own daughter. It’s curious how by the end of the movie the mother is not only blaming the son, but the son the mother, and it’s the stumblebum father who emerges with some credit for at least blaming himself.

A film like this is refreshing and startling in the way it cuts loose from formula and shows us confused lives we recognize. Hollywood tends to reduce stories like this to simplified redemption parables in which the noble woman emerges triumphant after a lifetime of surviving loser men. This movie is closer to the truth: A lot depends on what happens to you, and then a lot depends on how you let it affect you. Life has not been kind to Beverly, and Beverly has not been kind to life. Maybe there’ll be another book in a few years where she sees how, in some ways, she can blame herself.