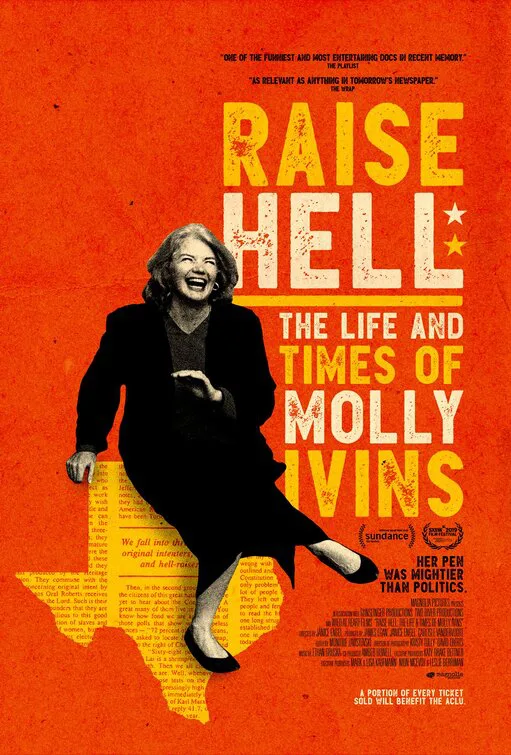

Texans will want to add an extra half-star to the rating at the top of this review, because there was never anybody like Molly Ivins before, and never will be again, and this documentary does a fine job of capturing what made her special.

For the uninitiated, Ivins was one of the last superstar newspaper columnists, a breed of celebrity that, in the age of digital media, is about to go the the way of the passenger pigeon and the red wolf. She wrote about Texas and national politics with the sharp eye and mordant sense of humor that you might’ve encountered while talking to a local newspaper’s government reporter in a bar on Friday night when they’ve had a few drinks and begun telling off-color anecdotes about politicians that their editors probably wouldn’t have allowed in print for fear of triggering a slander suit. I grew up reading her work in one of my hometown newspapers (the Dallas Times Herald, which was bought and closed in 1990 by its rival The Dallas Morning News to get rid of the competition).

It was through Ivins’ writing that I and a lot of other folks started to understand the depth of the relationship between capitalism and representative democracy, which were always aspects of the same business (or as Ivins would type it, “bidness”) throughout U.S. history. Ivins also wrote insightfully about how politicians shaped their images to play to constituencies, to the point of seeming like self-caricatures to anyone who wasn’t already inclined to support them. But unlike other columnists who followed Ivins and treated politics as a big show—like Maureen Dowd, who won a Pulitzer for writing what amounted to political fan-fiction—even the most scathingly funny and wild Ivins columns were undergirded by a sense of moral outrage that so many elected representatives were lining their own pockets or the pockets of donors rather than serving the people who voted for them.

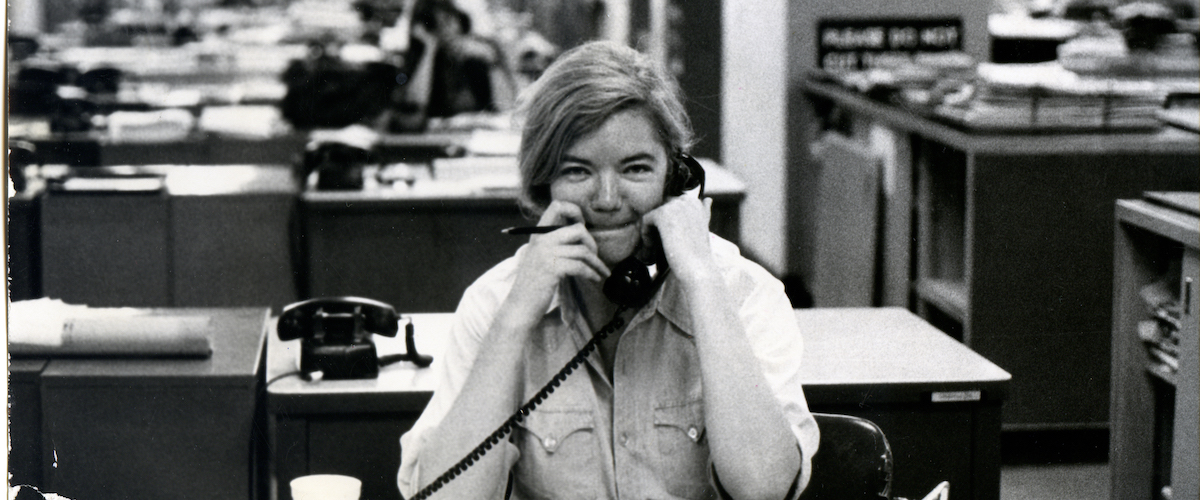

From the start, “Raise Hell” establishes that Ivins was an anti-authoritarian sensibility trapped in an industry that usually strove to avoid offending or challenging anyone. She was born and raised in a privileged part of Houston, regularly argued with her right-wing oil executive father, went off to Smith College, and in her twenties became co-editor of the Texas Observer (one of the few progressive outlets in a reactionary state). Then her talent made her a rising star at the Houston Chronicle and (briefly) the New York Times. Her first collection of writing, Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She? became a national bestseller and made Ivins a fixture on national talk shows (David Letterman, in particular, adored her).

Everyone else will appreciate the research, empathetic quotes, and bouncy musical cues assembled by Engel and her team, on behalf of a traditionally-told biography of a woman who was truly a legend, not just in her own mind. As told here, Ivins’ story hews to a traditional (or ordinary) biopic structure, moving through her life chronologically, spiking the narrative punch bowl with clips from her appearances on television (C-SPAN does a lot of heaving lifting) and quasi-ironic historical footage of Texans whooping and hollering and square-dancing. There are fond remembrances by other famous Texans, including former CBS anchor Dan Rather, Texas Observer founder Ronnie Dugger, and, via archival footage, the late former Texas governor Ann Richards.

Ivins’ story ultimately builds to Ivins getting shut out of her hometown daily, the Chronicle, in the post-9/11 era, because the publisher was a pal of then-president George W. Bush, and couldn’t stomach Ivins’ warnings that Bush, a former Texas governor, was an anti-intellectual who had pushed the country into an unnecessary war in Iraq that was bound to become a disastrous occupation. The film’s melancholy final stretch deals with Ivins’ battle with cancer, which she didn’t engage all that forcefully (according to friends) because she’d been drinking and smoking heavily her entire life, and decided to ramp it up because, as she put it, “I’ve already got cancer.”

The movie is affectionate overall, but stops short of being an uncritical advertisement for Ivins as a writer and person. We learn about how wantonly cruel she could be towards her targets (Ivins herself said that her type of humor was oppositional and destructive). And the second half of the movie, which concentrates on Ivins’ absolutist defense of the First Amendment even in cases of fascist ideology and hate speech, may rankle some viewers who otherwise agree with her politics. (It’s easy to imagine Ivins being claimed by the right as a hero for this reason, despite her opposition to nearly every other position American conservatives stand for.)

What emerges strongly from “Raise Hell” is a sense that, despite her awesome storytelling gifts and fearless personality, Ivins was ultimately a mystery to herself, just like almost everyone else who’s lived on the earth. I don’t think it does her a disservice to suggest that, based on the information assembled here, the writing and crusading on behalf of others might’ve been a re-direction of energy that a different type of writer might have directed towards their own psyche and experience. She turned more introspective towards the end, publicly declaring herself an alcoholic, writing and speaking about her cancer, and appearing in public bald without a trace of self-consciousness. You get the sense that Molly Ivins’ life and career ended just when she was getting warmed up.