Like an overloaded airplane struggling to lift off, the characters in “Pushing Tin” leap free of the runway, only to be pulled back down by the plot. John Cusack and Billy Bob Thornton play two air-traffic controllers who are prickly and complex, who take hold of a scene and shake it awake and make it live, only to be brought down by a simpering series of happy endings.

For at least an hour, there is hope that the movie will amount to something singular. It takes us into a world we haven’t seen much of–an air-traffic control center. Controllers peer into their computer screens like kids playing a video game, barking instructions with such alarming quickness that we wonder how pilots can understand them. They use cynicism to protect themselves from the terrors of the job. One guy “has an aluminum shower in his future.” The movie opens with the laconic observation, “You land a million planes safely, then you have one little mid-air, and you never hear the end of it.” This movie is not going to be shown on airplanes.

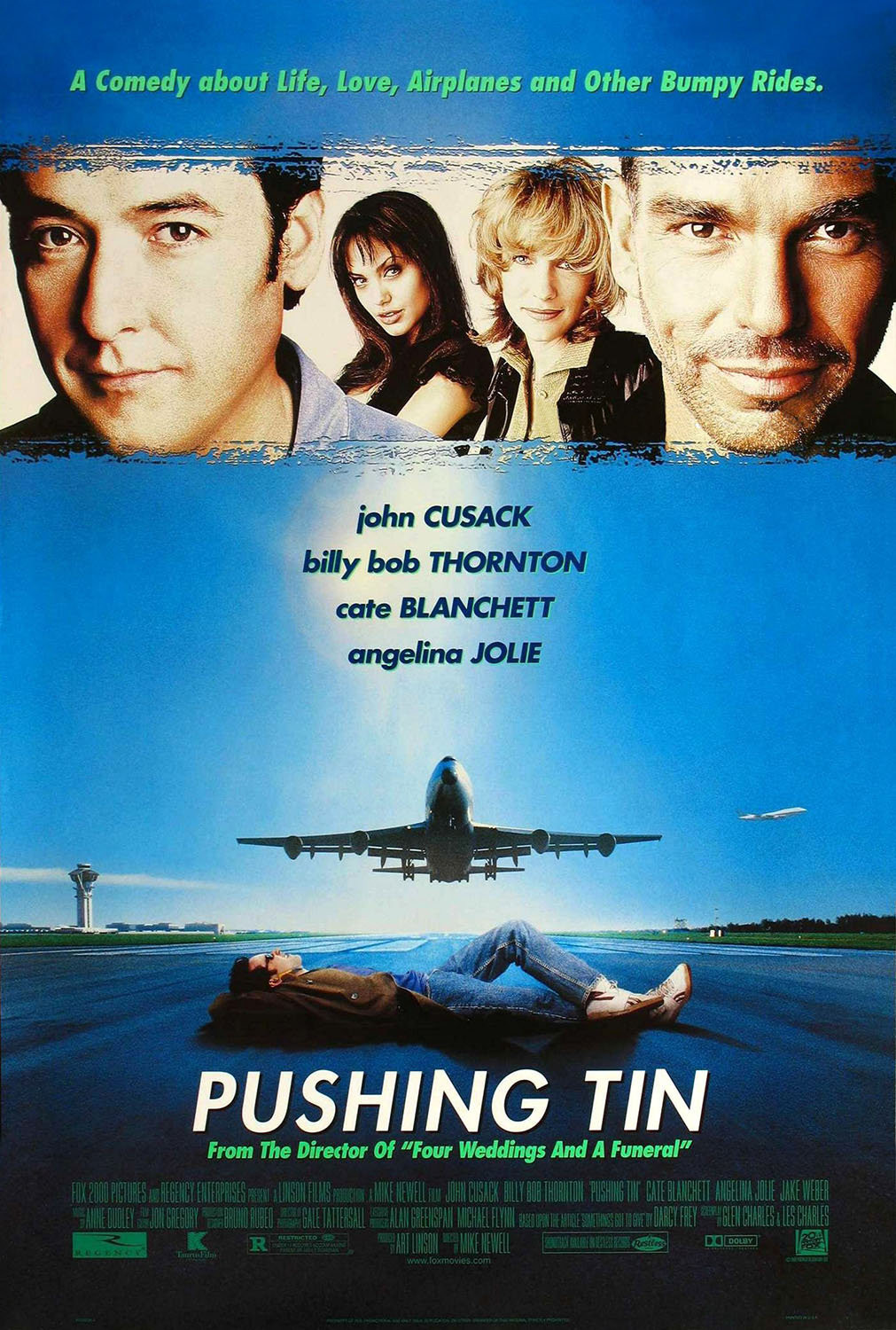

Cusack plays Nick Falzone, hotshot controller, on top of his job, happily married to his sweet wife Connie (Cate Blanchett, astonishingly transformed from Elizabeth I into a New Jersey housewife). He works a night shift, ingests a plateful of grease at the local diner, is tired but content. Then into his life comes Russell Bell (Billy Bob Thornton), a cowboy controller from out West, who gets under people’s skins. He rides a hog, needs a shave, schedules planes so close together that the other controllers hold their breaths. He’s married to a 20-year-old sex bomb named Mary (Angelina Jolie), who dresses like a lap dancer.

These four characters are genuinely interesting. Russell is an enigma and likes it that way. He seldom speaks, has tunnel vision when concentrating on a task, and once stood on a runway to see what the backwash from a 747 felt like. (The controllers watch him doing this, in a video that shows him blown away like a rag doll; in real life, paralysis or death would probably result.) Thornton, who is emerging as the best specialist in scene-stealing supporting roles since Robert Duvall, is able to maintain the fascination as long as the screenplay maintains Russell’s mystery.

Alas, Hollywood grows restless and unhappy with characters who don’t talk much; that’s why the typical American screenplay is said to be a third longer than most French screenplays. It’s hard to be chatty and still maintain an air of mystery; the key to Bogart’s appeal is in enigmatic understatement. When Russell does start speaking (or “sharing”) with Nick, he turns out, alas, to have the mellow insights of a self-help tape, and at one point actually advises the younger man to learn to “let go.” This is not what we want to hear from the same man who, earlier in the movie, asked if he has any hobbies, growls, “I used to bowl, when I was an alcoholic.” The Cusack character is also given a rocky road by the screenwriters (Glen and Les Charles, creators of the hit TV series “Cheers”). He’s a happily married man, but when he sees the Angelina Jolie character, he melts. She’s weeping in the supermarket over a cart full of vodka, and he helpfully invites her to a nearby restaurant. After predictable consequences, she has a line that would have made her husband proud (“Mr. Falzone, what’s the fewest number of words you can use to get out that door?”), but instead of following the emotional and sexual consequences to some kind of bitter end, the movie goes all soft and sentimental.

Cusack does what he does best: incisive intelligence, combined with sincere but sensible emotion. Blanchett, eccentric in “Oscar and Lucinda” and regal in “Elizabeth,” is cheery and normal here, chatting about taking art classes. Jolie’s sexuality is like a bronco that keeps throwing her; she’s too young and vulnerable to control it. One can imagine a movie that linked these characters in unforgettable ways, and this one seems headed for a showdown before it veers off into platitudes.

At least it spares us an airplane crash. And it gives us a good scene where Nick, onboard a plane, becomes convinced that Russell is steering them through a thunderstorm. (His behavior here should get him handcuffed by the flight crew and arrested by the FBI, but never mind.) The movie also does an observant job of showing us the atmosphere inside an air traffic control center, where the job description includes “depression, nervous breakdowns, heart attacks and hypertension.” The movie is worth seeing, for the good stuff. I’m recommending it because of the performances and the details in the air-traffic control center. The director is Mike Newell (“Donnie Brasco,” “Four Weddings and a Funeral”). His gift in making his characters come alive is so real that it actually underlines the weakness of the ending. We believe we know Russell and Nick–know them so well we can tell, in the last half hour, when they stop being themselves and start being the puppets of a boring studio ending.