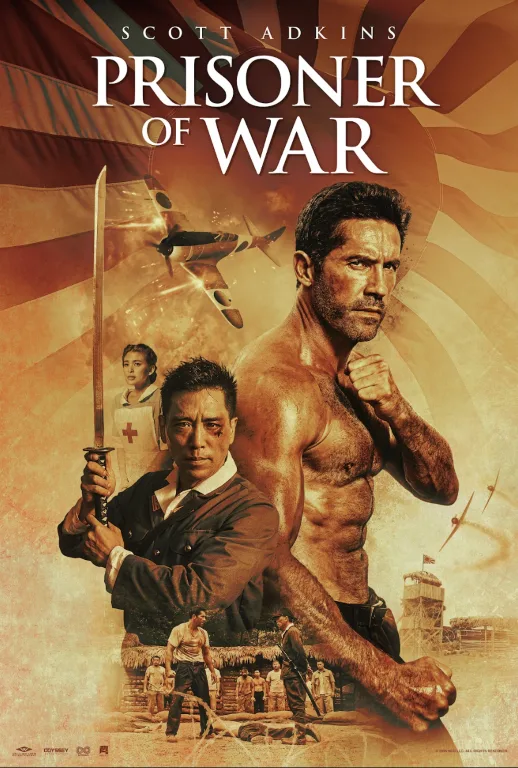

Martial arts fans will want to see the WW2 action thriller “Prisoner of War” either because of or in spite of star Scott Adkins. Adkins remains one of the most prolific and hard-working genre stars, though he doesn’t always seem to know how to bring out the best in himself beyond his show-stopping fight scenes.

“Prisoner of War” is a fine showcase for the British mixed martial artist whenever it’s only about a man of action who, when pressed, can take on all challengers. The movie’s Japanese POW camp setting, along with its underdeveloped and overlong prison break plot, trots out more clichés about honorable wartime conduct than you might care for, especially given where Adkins’s irrepressible Wing Commander Wright tries to escape from. Trapped in Bataan, Wright must escape a historically dire fate. This movie never makes Wright’s circumstances seem that threatening for him, though, which only gives him so much room to flex.

A white Brit among downtrodden (and primarily white) American soldiers both is and isn’t a surprising role for Adkins, who produced the movie and is credited with its story. Adkins dabbled in war movie revanchism in “Savage Dog,” a mostly satisfying 2017 Indochina work camp drama. In that movie, Adkins plays a former IRA supporter who fights for his survival and his Indochinese captors’ entertainment. In “Prisoner of War,” Wright fights for his survival and his Japanese captors’ entertainment.

We first meet Wright after Bataan when he barges into a Japanese martial arts studio run by Shunsuke Ito (Kansuke Yokoi), the son of Wright’s prison camp nemesis. This prompts a movie-long flashback to the Philippines in 1942, where Wright leads some Americans, including the capable but unexceptional Captain Collins (Donald “Cowboy” Cerrone), to escape the sadistic Japanese Lieutenant Colonel Ito (Peter Shinkoda) and his cannon fodder soldiers. Wright handily dispatches Ito’s men whenever he’s not planning his escape with Collins and the gang. Nobody develops much of a personality while all this goes on, though some would argue that that’s average for this kind of low-stakes star vehicle.

In his best non-violent scenes, Adkins proves that he’s charismatic enough not to require an emotional range. He smolders with Charles Bronson levels of intensity during the opening and concluding scenes in Shunsuke’s martial arts dojo, which seems fitting since most of “Prisoner of War” appears to have been made with the variable quality of a Cannon-made Bronson picture.

That said, director Louis Mandylor seems to know enough about how to flatter Adkins that it makes the rest of the movie’s shortcomings seem even more frustrating. Adkins can and invariably does a lot simply by glaring. He deserves a movie that’s as good when he’s off-screen as when he’s front and center.

Unfortunately, movie logic only takes “Prisoner of War” so far whenever the characters joylessly set up the next big Adkins-centric payoff. As Collins, Cerrone has the most potential to be a show-stealing co-lead, though he never breaks out of his limiting role. Shinkoda also does what he can whenever Ito glowers back at Wright. That’s not enough to make Adkins break a sweat, especially given the prescribed roles of every other Japanese character. Filipina nurse Theresa (Gabbi Garcia) barely appears in a couple of scenes, as if her supporting character were held over from another movie.

Adkins and his team are careful enough to keep the focus on Wright so tight that you might not even mind that “Prisoner of War” limps along whenever Adkins’s character is absent. The movie’s fight scenes are strong thanks to Mandylor’s tendency to stick (physically) close to Adkins and his opponents without cutting off either stunt coordinator Stephen Renney or fight choreographer Alvin Hsing at the knees. The movie’s concluding swordfight may not be as thrilling as its hand-to-hand and foot-to-torso combat, but it’s still filmed and cut with an eye for presentation that’s not always a given in this type of movie.

What’s especially disappointing about “Prisoner of War” is seeing how little life there is in its dialogue and characterizations despite its creators’ ostentatious sensitivity for Wright and his adversaries’ mutual, if highly selective, regard for each other’s humanity. War may be hell, but there are rules, which Ito’s men naturally ignore.

In this limiting context, Adkins looks like the martial arts equivalent of Swiss Army savior Mark Wahlberg. He mostly coasts on his well-established charms here and never really pushes himself out of his comfort zone despite the physical challenges posed by his action scenes. “Prisoner of War” may sometimes deliver what you hope for, but it’s an otherwise sloppy outing for Adkins, who by now should expect more from himself and his audience.