“Presumed Innocent” opens on a shot of a jury box in an empty courtroom, the shadows dark along the walls, the wood tones a deep oxblood, the whole room suggesting that they should abandon hope, those who enter here.

On the soundtrack we hear Harrison Ford talking about his job as a prosecuting attorney, but as he speaks of the duty of the law to separate the guilty from the innocent, there is little faith in his voice that the task can be done with any degree of certainty.

“Presumed Innocent” has at its core one of the most fundamental fears of civilized man: the fear of being found guilty of a crime one did not commit. That fear is at the heart of more than half of Hitchcock’s films, and it is one reason they work for all kinds of audiences. Everybody knows that fear.

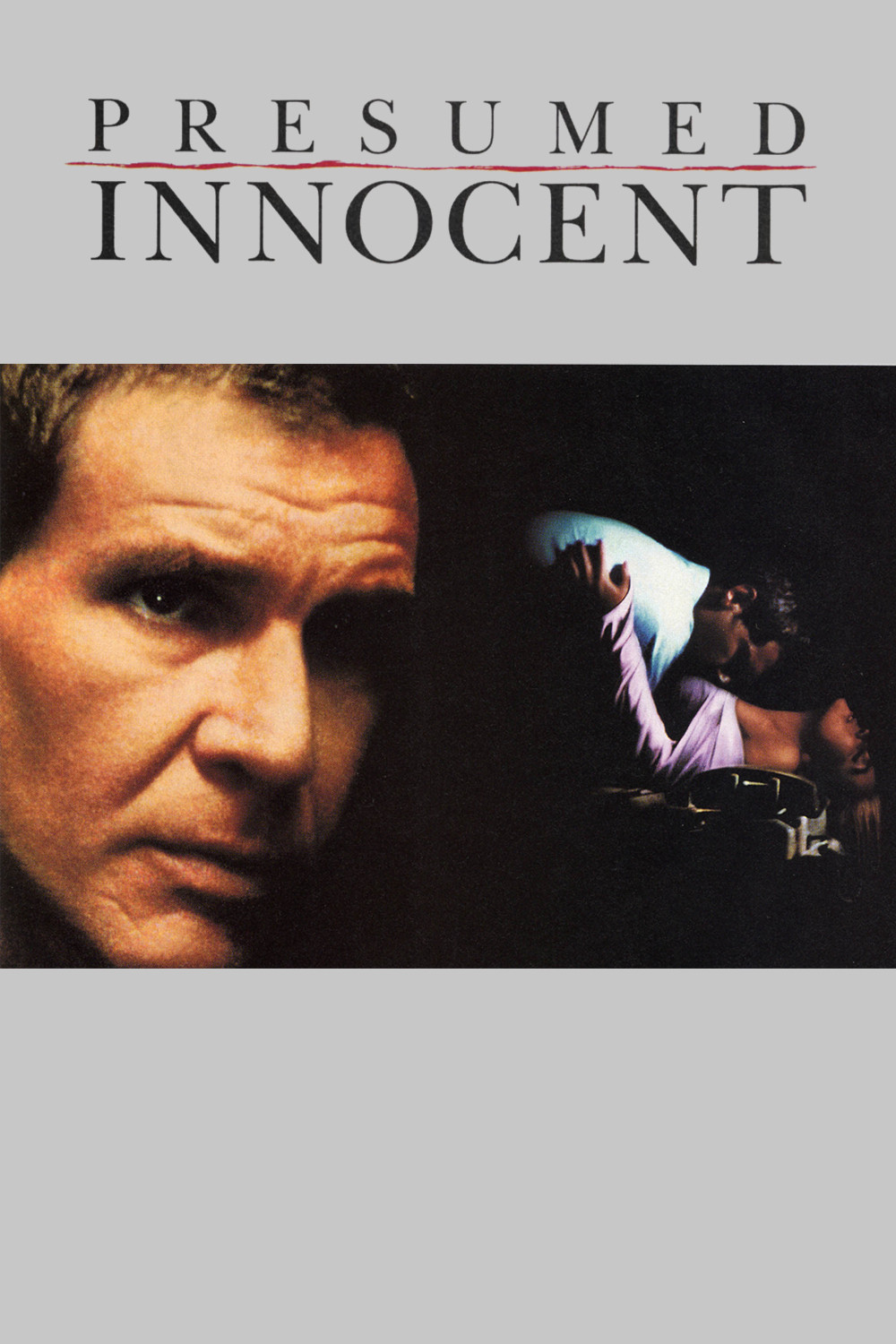

This movie is based on a best-selling novel by Scott Turow that became notorious for its explicit sexual content – for the detail in which it examined shocking gynecological evidence – and yet the sex wouldn’t have sold many copies without the fear. How do you defend yourself against a charge of rape when you were having an affair with the dead woman, and your fingerprints are on a glass in her apartment, and the phone records reveal that you called her earlier in the evening, and it would appear that your semen has been found at the scene of the crime? This is, as everybody knows by now, the dilemma in which Rusty Sabich finds himself, midway through “Presumed Innocent.” Sabich, played by Harrison Ford as a man whose flat voice masks great passions and terrors, plays an assistant state’s attorney who is assigned to the murder of a young woman lawyer in his office. Her name was Carolyn Polhemus (Greta Scacchi), and she had the ability to mesmerize men, especially those who could do her some good. Among those men, we discover, was Rusty Sabich himself – and also his boss, State’s Attorney Raymond Horgan (Brian Dennehy), who has assigned him to the case.

At first the investigation goes slowly, and then suddenly incriminating evidence surfaces, and the investigator finds himself named as the accused. The situation is made trickier because Dennehy faces an election in a few days. How does it look when the law and order candidate has a rapist and murderer on his own staff? The Ford character faces the complete collapse of his life as he knew it.

Standing by him, but bitter because of his infidelity, is his wife, played by Bonnie Bedelia.

I will not provide a single hint in this review as to whether Ford actually is guilty. Everyone who has read the book will, of course, have a good idea of what way the story is likely to unfold, but the producers have cleverly floated the notion that the film could turn out differently than the book. The best I can say is that, having read the novel, I was nevertheless in suspense during a great deal of the movie.

Even if you think you know what the solution is, the performances are so clever and the screenplay – by Frank Pierson and director Alan J.

Pakula – is so subtle that it could well turn out that your expectations are wrong.

Pakula has made film versions of difficult books before; “Sophie's Choice” and “All the President's Men” are among his credits. This time, his challenge was to avoid getting bogged down in the marshes of circumstantial and forensic evidence, which make good reading but can expand into interminable movie dialogue. The adaptation of Turow’s novel does a good job of presenting the evidence as needed, and no more than is needed, while allowing time for the characters to establish themselves.

The lead performance, by Harrison Ford, must have been a delicate balancing act, since at every point he must seem plausible both as a killer, and as an innocent man. Ford’s taciturn and undemonstrative acting style is well suited to the challenge. Greta Scacchi is well-cast, too, as the heartless Carolyn Polhemus, so warm and yet so cold. The Bonnie Bedelia performance as the wife is another tricky challenge, since she, too, must be ambiguous throughout. And the supporting performances include Paul Winfield as a judge with hidden motives, Raul Julia as a defense attorney who can’t get his client to stop acting like a lawyer, and Dennehy, expansive and yet with a wall of flint when it comes to saving his own skin.

This has been a summer of loud movies, of explosions and gunfire, screams and crashes. “Presumed Innocent” is a very quiet movie, brooding and secretive, about people who are good at masking their emotions. The audience I was with watched it with a hush. Part of the quiet was due to the absorbing nature of the story, I suppose, but a lot of it may have been caused by people reflecting, as I always do during stories like this, that there – but for the grace of God – go we.