When Mani Haghighi’s acerbic black comedy “Pig” opens, the camera wheels down a Tehran street following four teenage girls who are babbling to each other while simultaneously checking Instagram on their phones. Their conversation mainly concerns the recent split-up of a celebrity couple. The scene could be taking place anywhere in the world except that, this being Iran, the girls all wear hijabs along with their brightly colored knapsacks. Their happy chatter abruptly ends when a man rushes past them and they turn to see a horrified crowd staring at something in a curbside gutter – a man’s severed head.

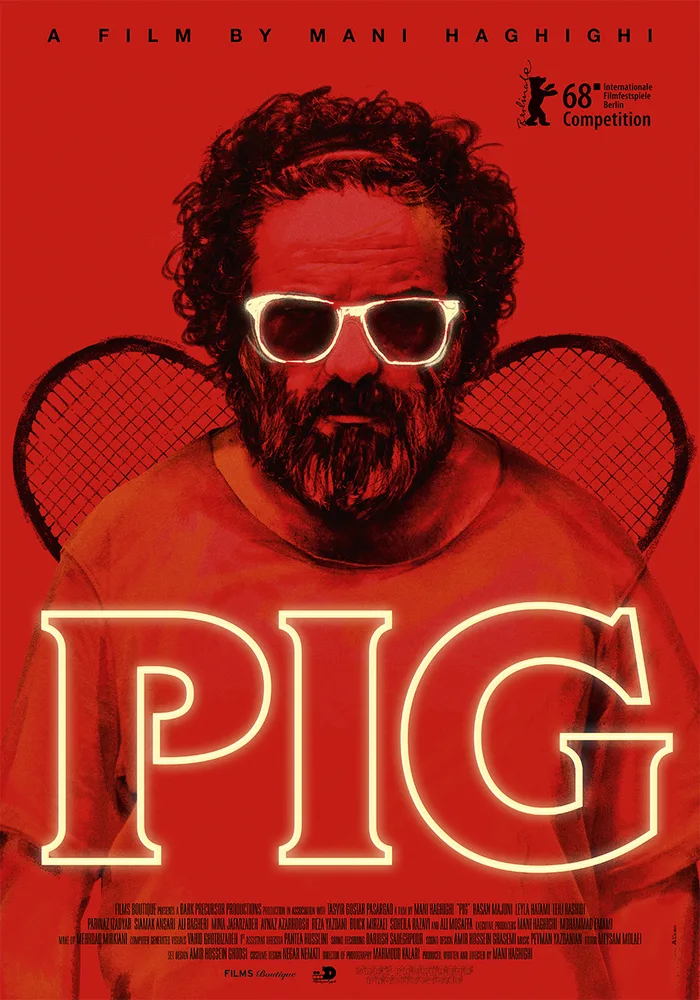

The head, in a particularly droll touch, is that of Haghighi, the writer-director of “Pig.” In the film’s central conceit, a murderer is stalking and decapitating Iran’s famous filmmakers, and leaving their heads with the word “pig” (in Farsi) carved in their foreheads. Haghighi, we learn, is the fourth victim (the previous three are named; they are all real directors who are still very much alive). This wacky premise allows Haghighi to do something that other artists must envy: he gets to stage his own funeral (or at least his head’s; the body is never found), complete with maudlin, hypocritical eulogies.

One not-at-all-bereaved mourner at this baleful gathering of the cream of Tehran’s film scene is the movie’s protagonist, Hasan Kasmai (Hasan Majuni), a director who has been blacklisted for two years. The authorities reject any feature he proposes, so he’s reduced to the indignity of directing TV commercials for a bug spray, complete with dancing women dressed up as insects who spit up fake vomit when the gas hits them. When we first see Hasan, before he goes to the morgue to identify Haghighi’s head, he’s in an orange AC/DC t-shirt storming through a trendy Tehran art gallery, where he tells a New York Times reporter (played by the Times’ Thomas Erdbrink) that the decapitations are owed to the fact that “They simply hate us!” But Hasan must also face the additional indignity that the killers perhaps haven’t come after him because they don’t consider him important enough.

If “Pig” doesn’t sound like the kind of Iranian film U.S. art house crowds have seen in the past – well, it is and it isn’t. In 1990, Abbas Kiarostami’s “Close-Up,” about a poor man arrested for impersonating a famous film director, established self-reflexive films-about-filmmakers as a distinctive Iranian subgenre, one often used to interrogate various aspects of Iranian society. In a sense, “Pig” belongs firmly in that tradition. Yet it is also something decidedly novel: a wildly original art-house comedy.

In attending Iran’s Fajr Film Festival the last two years, I was struck by the spirit of renewed artistic vitality I saw in the Iranian films there. That impression inspired me to co-found (with distributor Armin Miladi) the Iranian Film Festival New York, which had its first edition at the IFC Center last month. “Pig,” along with Bahman Farmanara’s “I Want to Dance” and Kamal Tabrizi’s “Sly,” were films in our lineup that exemplify the recent trend toward edgy comedy in Iranian cinema. All three inveigh against various forms of repression in Iran, and all push censorship boundaries in ways that would have been scarcely imaginable a few years ago. (In the case of “Pig,” I still can’t fathom how Haghighi got away with Hasan’s Busby Berkeley-like bug spray spot, since dancing females have long been one of the censors’ big no-nos.)

In a sense, “Pig” is like a double helix that intertwines the personal and the political. The personal side encompasses relationship quandaries that that wouldn’t look out of place in a Woody Allen comedy. Hasan’s blacklisting is giving him problems with his longtime mistress and leading lady Shiva (glamorous, heavily made-up Leila Hatami), who’s contemplating acting in a film by Hasan’s unctuous rival Sohrab Saidi (excellent Ali Mosaffa). Meanwhile, his wife (Leili Rashidi) and a daughter who acts as his assistant (Ainaz Azarhoush) don’t try to rein in his excesses and infidelities as much as shielding him from the various tempests his volatile nature generates. He also must contend with a social media stalker (Parinaz Izadyar), who adores his movies so much she worms her way into his bug-spray chorus line, and an increasingly senile mom (hilarious Mina Jafarzadeh) who’s given to wielding an antique rifle.

The political threads woven into this tapestry, meanwhile, are many and subtle, indicating the widespread but often opaque ways Iran exercises control over its citizens and artists. Though these are details, it’s significant that Hasan doesn’t know what he did to get blacklisted or when the ban will be lifted. The state’s ways are decisive and thorough but mysterious. And if the device of the beheadings strikes foreigners as outlandishly comical, it’s sure to be chilling to Iranians in recalling the “chain murders” of the late ‘90s, when a number of prominent dissidents and cultural figures were brutally murdered by shadowy security operatives (crimes that were dramatized in Mohammad Rasoulof’s “Manuscripts Don’t Burn”).

But the film’s indictment isn’t simply aimed at individual officials or their lethal accomplices. When Hasan says, “They hate us,” he’s indicating a yawning cultural chasm. On one side are the hated: artists, intellectuals and free-thinkers. On the other side are the haters: not only hardliners and their allies in the regime, but also the part of the population that’s intolerant enough to go along with any vindictive persecution of their supposed enemies. In this sense, “Pig” is going after an entire cultural dynamic, one in which art and repression are inextricably opposed.

In 2006, Haghighi and Asghar Farhadi co-wrote the latter’s “Fireworks Wednesday,” the film that, more than any other, arguably inaugurated the current era of Iranian filmmaking. Setting aside the model of contemplative, de-dramatized cinema using non-actors and impoverished or rural settings that filmmakers like Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf employed in the 1990s, the new model used movie stars in intricate, plot-driven tales about middle-class urbanites. The approach has taken Farhadi to the Oscars twice in the last decade. And it’s one that Haghighi has now shifted from dramatic to comedic purposes, while maintaining a strong undertow of pointed, purposeful social criticism. The filmmaker and his work deserve to be better known, and “Pig” is an ideal introduction to both for American audiences.