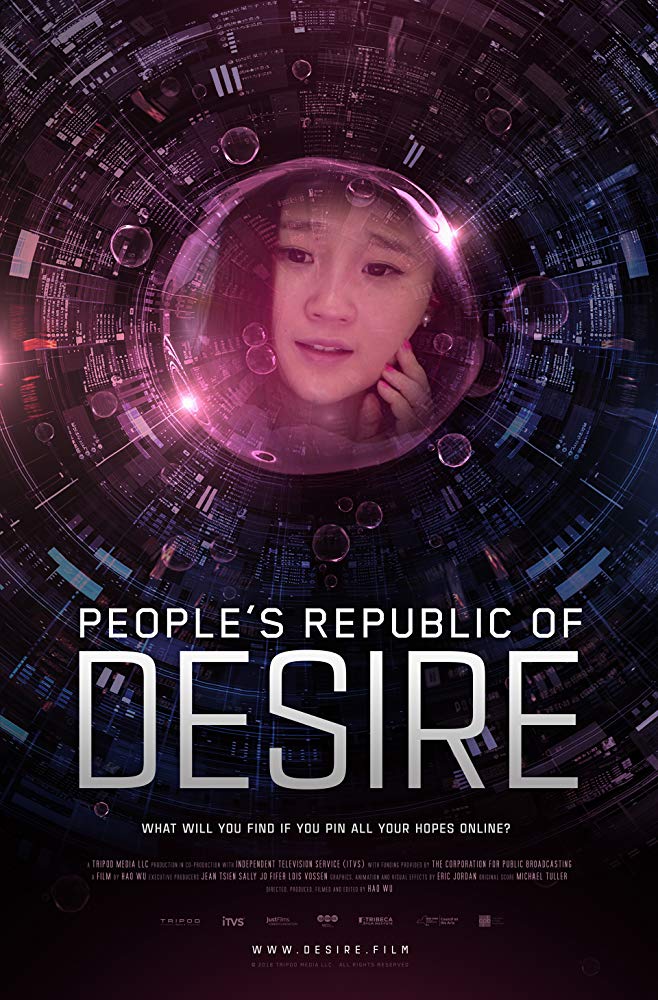

A young Chinese woman named Shen Man sits in front of her computer, in front of a camera, in front of five million followers. Some of her online audience members have a lot more money than others. She sings and talks to them as they shower her with compliments, cash. They’re all trying to get her affection, basking in her online presence. It’s a warped byproduct of celebrity and internet culture, and “People’s Republic of Desire” tells us that it’s the future that awaits our current iterations of YouTube vloggers and Twitch streams.

Man is one of a million-plus entertainers called “hosts” with the same work on YY, which appears to China’s equivalent of the West’s YouTube curdling vlog-life superstardom. YY makes superstars out of attractive and entertaining people like Shen Man, or the bombastic Big Li, who yells at his followers and calls them brothers. But the people in their online audience who don’t have a lot of money themselves but love seeing the success of their favorite hosts are called daosis, presented her as mostly young men and women who have very spare bedrooms and make only a few hundred a month. Their love of seeing the hosts become successful is further enflamed by tuhaos, people with a lot of cash to spare who the diaosis then root for to give money to the host. The only thing that’s sustainable about this cycle for anyone involved is society’s interest in witnessing fame and money firsthand.

Writer/director/editor Hao Wu frames his deep dive into this world around an annual host competition, in which the diaosis pay for votes to give to their beloved hosts, which then encourage the much wealthier tuhaos to raise the vote numbers even higher. It’s a sport, of sorts, with a sense of camaraderie and strategy, down to the diaosis saving what cash they have. To keep the money game even more sobering, it’s truly about the agencies who can help raise the vote numbers for their hosts. “People’s Republic of Desire” is equal shares fascinating and depressing, often at the same time.

There’s a lot going on here—not just with Wu trying to explain the system, a love triangle with hosts, diaosis and tuhaos, but the many plot developments to Shen Man and Big Li’s careers as they face irrelevancy and controversy. On top of that, there are a lot of food-for-thought revelations from people, about how one does not need talent to be a host, or how diaosis love hosts because they themselves have “nothing to show off.” The documentary is a true whirlwind, but grounded in the perpetual struggle of hosts and diaosis. Every time Wu cuts from the supposed grandeur of Big Li’s feed to a diaosi sitting in a very spare bedroom with a computer desk in a corner, it hurts.

Wu’s energetic approach to information and text flourishes within his storytelling, as he animates the experience of a host as if it were a movie theater, the host’s feed projected on the wall as diaosi icons cheer for tuhaos to swoop in with more money. And given that the film is working from a format that relies on texts, those streams of chats, Wu pops the words out of a particular device, instead of how many other filmmakers simply address it through subtitles.

As a movie that’s so deeply interesting it works even with editing that’s too touch-and-go, like when Wu briefly mentions at the beginning the financial structure of the all-encompassing YY, using a news report telling us that they split the money with hosts, before quickly moving on to something else. And Wu is very particular about when he wants you to know certain information. It is not until the very end, when we visit the YY headquarters, that he gives us an even bleaker idea of how much money truly is, and is not, being made by hosts.

Wu takes an observational, matter of fact stance to these different lives and this overall enterprise, reminiscent of how Kyoko Miyake took us through the looking glass of Japan’s idol culture in “Tokyo Idols,” another doc on a similar sociological beat that would make for a great double feature or essay. These two films, along with Shane Dawson’s recent YouTube documentary series about Jake Paul or the cam girl existential horror movie “Cam,” continue a tough conversation about the monster we have made from our desires, and how only money can challenge it.