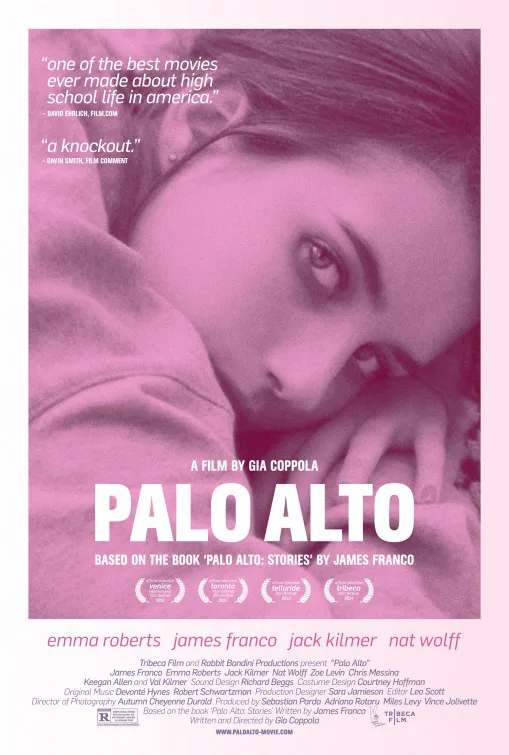

Gia Coppola, the 27-year-old granddaughter of Francis Ford Coppola and niece of Sofia Coppola, makes her directorial debut with “Palo Alto.” Coppola also wrote the screenplay, adapting James Franco‘s short story collection of the same name. Franco was instrumental in helping get the film made, for, despite her last name, it was not easy for Coppola to find financing for the film, especially since there are no A-list stars in it and many of the young actors are newbies to the industry. Shooting on a very low budget, “Palo Alto” is a sensitively-filmed (the cinematographer was Autumn Durald) and dreamy-looking evocation of a group of aimless teenagers, usually stoned or drunk, circulating in a mainly adult-free world in the notoriously wealthy town of the title. “Palo Alto” is a very strong first feature, prioritizing mood over message. Coppola does not diagnose underlying societal problems; she does not make assumptions about the cultural void in which the kids live. She just shows us what they do, moving in and out of different narratives, interspersed with moody, misty shots of a mainly-empty-looking Palo Alto—street lamps at night, quiet playgrounds, sunset hitting the tree tops. It all feels a little bit like a dream, like the characters will look back on it and think, “Did it really happen like that? Or was I just stoned the whole time?”

The main characters are Teddy, played by newcomer Jack Kilmer, son of Val Kilmer, who has a funny cameo as a perpetually stoned, video-game-playing stepdad. Teddy is a good kid who likes to draw and has a crush on soccer-playing April (Emma Roberts). He drinks to excess, and one night crashes his car while drunk, getting himself a stint of community service at a children’s library. Teddy’s best friend is the volatile Fred (an excellent Nat Wolff). Fred is an aggressive, combative, troubled kid (when you meet his father, played with beautiful creepiness by Chris Messina, you get a glimpse of the origin of Fred’s problems). Fred picks fights, treats girls horribly, and seems, somehow, dangerous. April, played by Roberts, is shy and serious, and has a crush on her soccer coach Mr. B. (played by James Franco). Mr. B. is a good coach, but he also has this way of maintaining eye contact with April in a way that seems…too much, too intense. April babysits for Mr. B.’s young son. Lastly, there is the fascinating Emily (Zoe Levin), an isolated girl, beautiful and blonde, who services every boy in the class as though she has been hired for the job, and yet says at one point, with eerie blankness, “I’ve never been in love.”

These four narratives shift and merge, dissecting and diverging. Parents don’t really “count” in this world. April’s Botoxed-mother hovers around her daughter in the kitchen, hugging her, saying “I love you so much!” It feels anxious rather than sincere. The guidance counselor at the school is useless, with dead plants filling up her makeshift office. Mr. B. clearly has a thing for teenage girls, and April falls under his sway for a time. It’s exciting for her. At the same time that he is flirting with her after hours, he stops encouraging her at soccer practice, stops speaking to her at school. His behavior is hurtful and manipulative. During one of their encounters, there are insert shots of parts of April’s face—her lips, her eyes, covered in bands of shadow, a beautiful editorial choice on Coppola’s part, showing the dissociation going on for April in a purely visual way.

Clearly, the kids lack role models, but they don’t even seem to know they need them. College is still far off. There are repeated, connected shots of each kid doing whatever it is that they do when they’re alone: dancing around in their messy rooms, playing guitar, texting, smoking (all of the kids smoke like chimneys), etc. Teddy’s crush on April is sweet, and recognizably human, at least in contrast to the debauchery seen in the rest of the school, but the two of them don’t know how to access those softer feelings. They are clearly drawn to one another. It makes them shy; it makes them not know what to say. All of the young actors here are amazing in their respective roles. And while Teddy and April feel like the “leads,” Emily and Fred, more troubled, more damaged, haunt the periphery, making you wonder, truly, what the hell is going to become of these two individuals?

“Palo Alto” has a contemplative feel of darkness and languor, and the score is woven beautifully into the action. The music feels like an integral part of the mood of the film, as opposed to indie hits being imposed on the narrative from the outside. “Palo Alto” is not like other, current films about teens, films that ache with hopelessness and alienating nihilism. “Palo Alto” sees the sweetness that is there, too, struggling to express itself, and to survive.