Even if you know nothing of jazz or Oscar Peterson, the subject of Barry Avrich’s “Oscar Peterson: Black + White,” the new documentary will at least convince you that the pianist was an all-time great; a child prodigy who transitioned to an accoladed adult career without missing a beat, a master of his craft who could outplay anyone from the time he was a young teen until when he stopped touring in 2007 not long before his death. Even a stroke in 1993 that left Peterson with severely reduced mobility in his left hand only kept him off stage for less than two years, as he retrained himself to play up to his own sky-high standards with only one functioning hand.

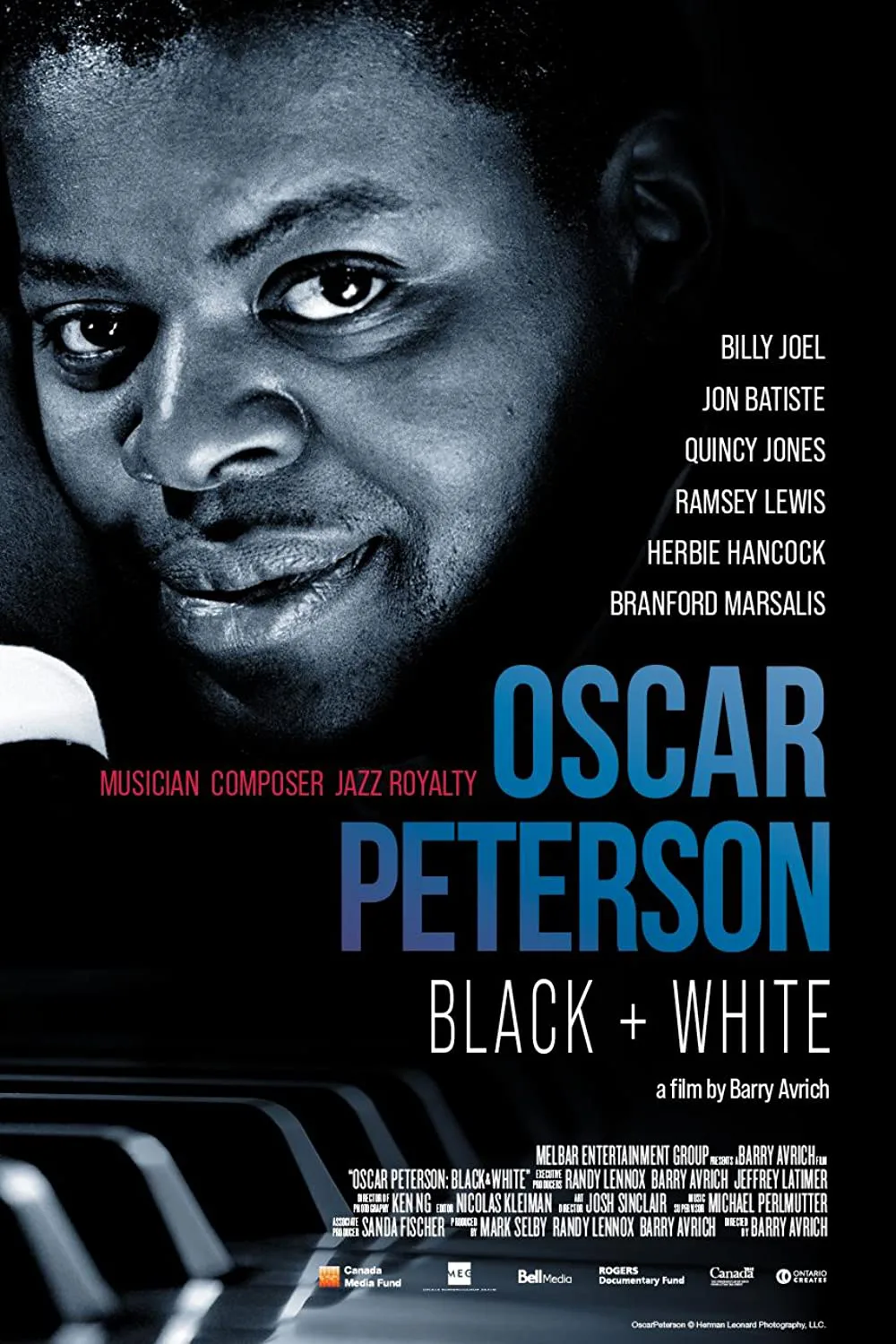

Avrich’s documentary features an impressive wealth of archival footage and a compelling range of interview subjects, from friends and colleagues of Peterson, to prominent historians and jazz critics and famous admirers, including Billy Joel and Jon Batiste. The charmingly earnest enthusiasm for Peterson that practically radiates from the documentary gives the proceedings an especially endearing air. But the film suffers from the standard pitfalls of a laudatory Great Man biopic that lacks any angle more specific than shining an admiring spotlight on its subject—in trying to encompass a whole life in 90 minutes, its breadth renders any particular depth impossible.

While its wide range of interview subjects and extensive archival material speaks well of the amount of research that went into crafting the documentary, this same wealth of material also helps lure the film into the trap of making the same points over and over. Sure, it adds emphasis to show numerous people reiterating how Peterson had an almost preternatural dexterity, but the sheer number of different sources enables the film to fill a lot of space talking about Peterson without saying all that much of any deeper significance. Many of the most interesting glimpses of insight into Peterson come from archival footage of the man himself. The talking heads occasionally help provide context, but far more often just paraphrase or parrot back what is addressed in the archival instead of building on it in any meaningful way.

The titular “Black + White” is a clear reference to piano keys, but it’s impossible not to also see here an allusion to the role of race in it all, with Peterson being a Black man who rose to prominence in the 1940s, first in Canada and then in the United States. Save for in the very beginning, which briefly addresses Peterson’s relationship with his parents, West Indian immigrants who settled in Montreal, the only real mentions of Peterson’s personal life for the first two-thirds of the film are fleeting references in archival audio from Peterson himself. And while there are a few throwaway lines here and there about the racism Peterson faced over the course of his life and career, the movie oddly never really digs into how Peterson’s identity as a Black Canadian man played a role in his musical career or personal life, especially throughout his time touring in the US, including the segregated South, throughout the Civil Rights movement.

For instance, we only briefly hear about “Hymn to Freedom,” one of Peterson’s early major original compositions that, after Harriette Hamilton added lyrics, became an anthem of the US civil rights movement in the 1960s. However, the film’s brief synopsis of this fails to provide enough context to take away much from this particular chapter of Peterson’s life. It never really even addresses at what stage Peterson made the step from being a performer to composing original works—how that came about, how he felt about it, how audiences felt about it. Anything that would help paint a clearer picture.

“Oscar Peterson: Black + White” starts off as an adoring if straightforward celebration of Peterson’s music and legacy and would have been much better off remaining in its comfort zone. Bu the movie later attempts to shift gears into something far more personal and searching, and it consistently fails to provide enough context about Peterson’s marriages and family business for most of its revelations to mean all that much. In trying to pivot to something a bit deeper and more intimate, more Peterson the man than Peterson the legend, the documentary’s last half hour instead turns into something far more muddled and ineffective.

Avrich’s film also fails to make consistent key choices about what kind of audience it’s targeting, sometimes offering rather broad commentary in one hand, but then with the other hand throwing out a lot of names and dates in passing that would mean a lot to a jazz aficionado, but are rather opaque to the uninitiated. Sometimes the film feels very geared towards existing fans, other times seeking to introduce newcomers to Peterson’s legacy, and through this inconsistency fails to feel truly suited to audiences on either end of the spectrum.

There’s enough here in the sheer wealth of material that fans of Peterson’s or jazz could find this documentary worth the runtime. But it’s unfortunate that Avrich and his team were not able to shape this material into an overall stronger narrative.

Now playing on Hulu.