“Orphans” is a good play about behavior that has been turned into a mediocre movie about nothing much at all. That is not intended as a criticism of the filmmakers, but simply as an observation about the nature of the material.

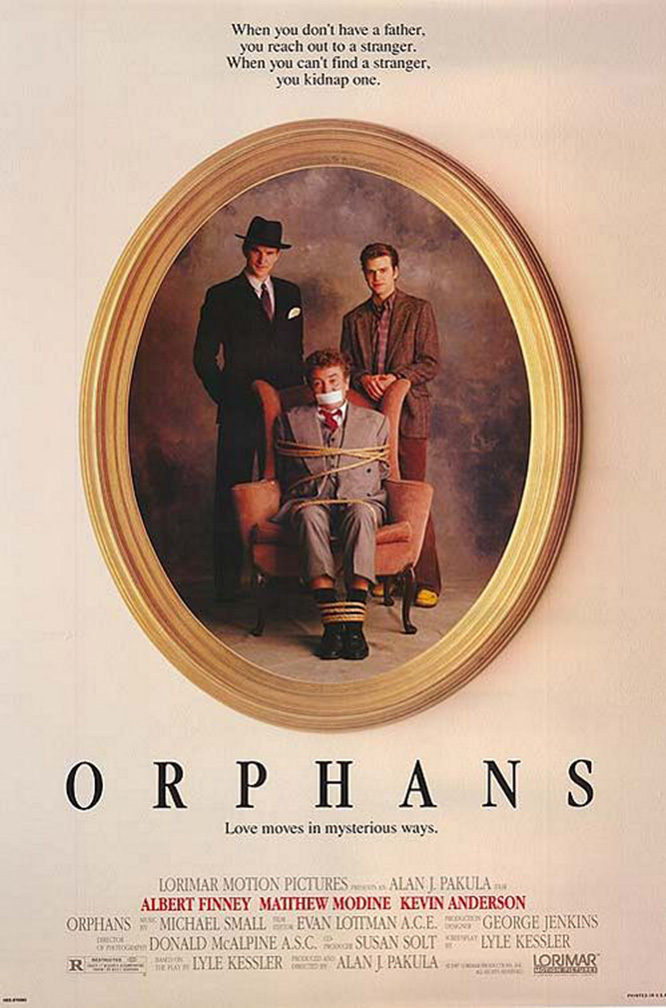

Although it is possible to construct elaborate theories about this movie, you blink and they’re gone. “Orphans” is not about a man who wants to be a father, or about boys who want to have a father, or about sublimated sexual desires, or about the underlying bond between criminals and outcasts. It is about shouting and jumping around and posturing and eccentric behavior. The movie stars Albert Finney as a Chicago gangster who travels to Newark with a briefcase full of negotiable bonds and promptly gets drunk out of his mind in a tavern. He runs across Matthew Modine, a street punk, and instantly sentimentalizes him as a Dead-End Kid – perhaps out of some maudlin idea the gangster has of his own childhood. Finney gets even more drunk, passes out and wakes up tied to a chair. He has been kidnapped by Modine, who lives with his brother (Kevin Anderson) in a crumbling house in the middle of an urban wasteland. Finney never loses his cool. He frees himself of his bonds and then, amazingly, does not take the opportunity to escape. Instead, he stays in the house, cleaning and painting it, and appoints himself to tutor the two brothers in the ways of the world. His task is to tame and domesticate Modine, who is too hot-tempered, and to free Anderson of self-imprisonment (the kid hasn’t even been outdoors in years, because Modine has convinced him he’s allergic to the outside world).

Modine has a stake in keeping his brother imprisoned. It gives him power and a godlike role in their small world. Finney works artfully, using object lessons, parables, and question-and-answer sessions, feeling his way, talking these kids into a new view of themselves. There is a lot of stage business for him to perform while he talks. He paints, does carpentry, plays with his gun, and watches while Anderson swings from the curtains and tumbles around the set like a monkey in a cage. Modine alternates between aggression and passivity; he takes a strong line at first but eventually confesses his ignorance to the older man.

This sort of material is strong on the stage. You enter the same time and space as the actors, and the lights go down, and they project great energy at the audience, which leaves feeling slightly more dangerous and alive than when it entered the room. It is a very satisfactory experience. Plays such as Lyle Kessler’s “Orphans” and Sam Shepard’s “True West” (with its suite for pop-up toasters) can be considered as concerts for voices and movement. The playwright supplies the words and suggests the actions, and the actors cry and whisper, leap and crouch, fight and surrender, and reveal great hurts from their pasts. Along the way, it is important, of course, that they change and that they discover some measure of the truth about themselves.

Actually, change and truth are the least important ingredients, because they are the most arbitrary and artificial, put in to make the behavior look like a real play. The actual physical and verbal behavior itself is the subject of the play. It is possible to construct elaborate theories about the meaning of “Orphans,” but on the stage, the play works as an exercise in human vitality, in which the actors test their instruments. On screen, where the impact of their actual physical presence is missing, the material is revealed as a series of contrivances.

Finney, who does an excellent job of portraying Harold, the gangster, probably realizes this. He saw the play in Chicago, brought it to London and performed it triumphantly on the stage. Of course a movie had to be made of it, and he was happy to play his role again. But when I talked to him not long ago, he spoke of the play almost entirely in stage actor’s words, in terms of the opportunities it gave him rather than in the statement it made. That’s the right approach.

The theater works best when it places the audience in the same box of space and time as the actors and the material. Movies work best when they break out of the box, when they spring free from the physical constraints of space and time – even in such a simple matter as the way the camera’s point of view is free to roam. The problem of filming a play is as old as the cinema itself, and “Orphans” doesn’t solve it – not that this play could be successfully filmed. Pakula and his actors do their best, but “out there” feels as much like “offstage” at the end as at the beginning.