When a man tells a woman she’s the one he’s been searching for, this is not a comment about the woman but about the man. The male mind, drenched in testosterone, sees what it needs to see. “One Night at McCool’s,” a comedy about three men who fall for the same woman, shows how the wise woman can take advantage of this biological insight.

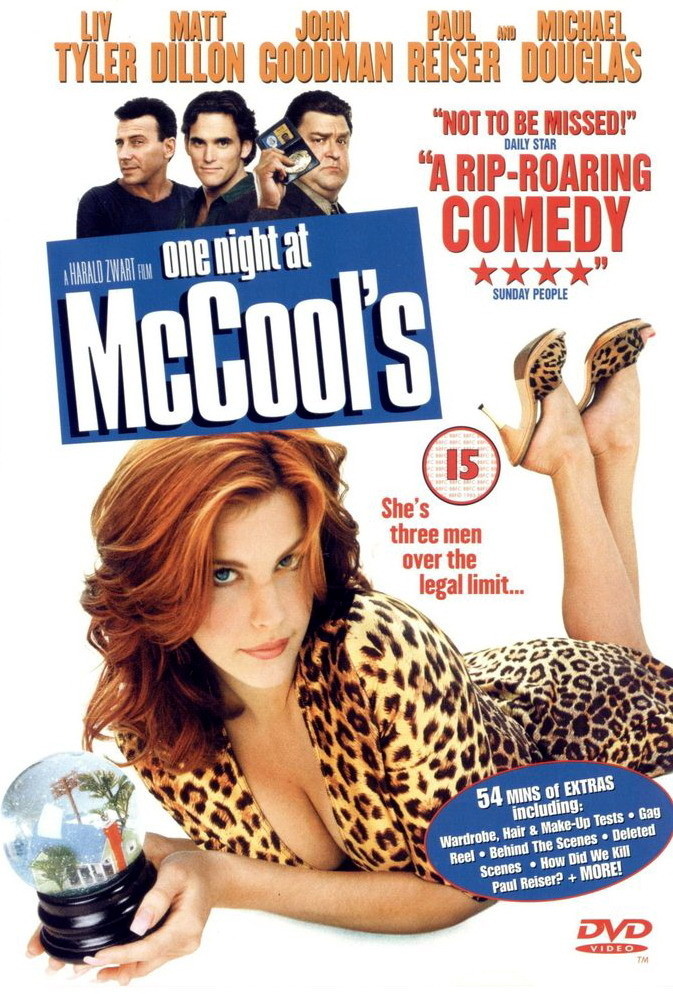

The movie stars Liv Tyler as Jewel Valentine, a woman who walks into a bar one night and walks out, so to speak, with the hearts of three men. Each one sees a different woman. For Randy the bartender (Matt Dillon), she’s the sweet homemaker he has yearned for ever since his mother died and left him a house. For Carl the lawyer (Paul Reiser), she’s a sexpot with great boobs and legs that go all the way up to here. When Dehling the detective (John Goodman) sees her a few days later, she’s like an angel, backlit in soft focus, as if heaven has reincarnated his beloved dead wife.

Much of the humor of the case comes because when Jewel looks at Randy, Carl and Dehling, she sees three patsies–men who can feed her almost insatiable desire for consumer goods. She may sorta like them. She isn’t an evil woman; she’s just the victim of her nature. She’s like the Parker Posey character in “Best in Show,” who considers herself “lucky to have been raised among catalogs.” Like movie sex bombs of the past, Tyler plays Jewel not as a scheming gold digger, but as an innocent, almost childlike creature who is delighted by baubles (and by DVD machines, which she has a thing for). At least, I think that’s what she does. Like the audience, I have to reconstruct her from a composite picture made out of three sets of unreliable testimony. Perhaps there is a clue in the fact that the first time we see her, she’s with a big, loud, obnoxious, leather-wearing, middle-age hood named Utah (Andrew Dice Clay). On the other hand, perhaps Utah is a nicer guy, since we see him only through the eyes of his rivals.

We see everything in the movie through secondhand testimony. Like Akira Kurosawa’s “Rashomon,” the film has no objective reality; we depend on what people tell us. Jewel waltzes into each man’s life and gets him to do more or less what she desires, and what she desires is highly specific and has to do with her relationship to the consumer lifestyle (to reveal more would be unfair). Each guy of course filters her behavior through the delusion that she really likes him. And each guy creates a negative, hostile mental portrait of the other two guys.

Each witness has someone to listen to him. Randy, the bartender, confides in Mr. Burmeister (Michael Douglas, buck-toothed and in urgent need of a barber). He’s a hit man Randy wants to pay to set things straight. Carl, the lawyer, talks to his psychiatrist (Reba McEntire), who thinks the whole problem may be related to his relationship with his mother, and may be right. And Dehling the detective talks to his brother the priest (Richard Jenkins).

Jewel is not the only character who is seen in three different ways. Consider how Randy the bartender comes across as a hardworking, easygoing guy in his own version, but appears to others as a slow-witted drunk and a letch.

The movie isn’t only about three sets of testimony. Far from it. Jewel has a scam she’s had a lot of luck with, and enlists Randy in helping her out–against his will, since he sees her as a sweet housewife. He can’t imagine her as a criminal, and neither can the cop, who torturously rewrites the evidence of his own eyes in order to make her into an innocent bystander who needs to be rescued by–well, detective Dehling, of course.

“One Night at McCool’s” does not quite work, but it has a lot of fun being a near-miss. It misses, I think, because it is so busy with its crosscut structure and its interlocking stories that it never really gives us anyone to identify with–and in a comedy, we have to know where everybody stands in order to figure out what’s funny, and how, and to whom. The same flaw has always bothered me about “Rashomon”–a masterpiece, yes, but one of conception rather than emotion.

We enjoy the puzzle in “McCool’s,” and Tyler and her co-stars do a good job of seeming like different things to different people, but it’s finally an exercise without an emotional engine to pull it, and we just don’t care enough. Does it matter if we don’t care about a comedy? Yes, I think, it does: Comedy needs victims, and when everybody is innocent in their own eyes, you don’t know where to look while you’re laughing.