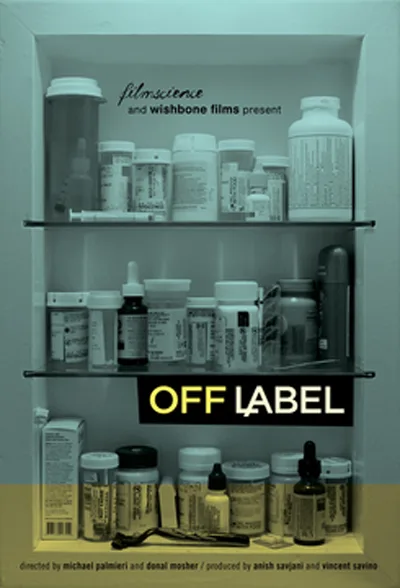

The documentary “Off Label” attempts to tackle the totality of transgressions within the pharmaceutical industry in just 75 minutes through the eyes of eight people scattered across the country, all of whom have had wildly disparate experiences.

There’s Paul Clough, a former foster kid who’s now essentially homeless, except for when he’s staying in a series of cheap motels while serving as the test subject for new drugs. He also barely gets by making balloon animals on the Las Vegas Strip for tips.

There’s Jusef Anthony, who agreed to take part in clinical trials while doing a brief prison stint in Pennsylvania the mid-1960s. Fifty years later, he suffers from a variety of ailments, including prostate cancer and hepatitis C. He believes his Muslim faith will save him.

There’s Jordan Rieke, a vagabond who met his equally pierced-and-tatted fiancée while hopping freight trains. Now, living in Rochester, Minn. – home of the Mayo Clinic — he’s saving money for their wedding by working as a pharmaceutical guinea pig.

And there’s Mary Weiss, whose mentally ill son, Dan, committed suicide in gruesome fashion at age 26 because the psychiatric drug trials he underwent further exacerbated his already-fragile state. The Minneapolis woman carries some of his ashes in a pouch around her neck as she fights for reform.

“He didn’t pass away. They let him die,” Weiss says solemnly at the film’s start. “And they need to be held accountable.”

These stories and others featured in “Off Label” have undeniably compelling moments within them. But co-directors Michael Palmieri and Donal Mosher try to encompass so many people and so many angles in such a short amount of time, they end up breezing through them and providing glimpses that feel rushed and unsatisfying.

Only 20 minutes into the film, the structure feels meandering and repetitive. Perhaps if they’d focused on fewer people – or even just placed one person at the center who’s emblematic of a larger trend or problem – the result would have been a film that’s more poignant, more powerful.

Andrew Duffy’s story is a great example of the kind of missed opportunity that repeatedly plagues “Off Label.” (The title refers to the practice of prescribing pharmaceuticals for illnesses other than those for which they were designed, a former drug rep for Pfizer informs us.) A 22-year-old former Army medic who served in Abu Ghraib prison during the war in Iraq, Duffy is now back home in Iowa taking a variety of medications prescribed for his post-traumatic stress disorder. But he can only get the drugs made by companies that have deals with the VA hospital near his home, which often aren’t quite right.

“I don’t need medication,” Duffy says while reflecting on the horrors he witnessed. “I need help.” He could have been the inspiration for a film all to himself.

With each new damning anecdote, the question arises in the viewer’s mind: Are we going to see any sort of rebuttal to this? Are the filmmakers even going to make the slightest attempt to provide balance, or even a standard “no comment” from a pharmaceutical giant or two? They never do, and that omission not only feels like a gaping hole from a narrative perspective, it also weakens their argument.

Part of what makes Michael Moore’s documentaries so powerful, for example, is his deliciously awkward method of hunting down the elusive keepers of power and hammering them with questions he knows they’ll never answer. Palmieri and Mosher don’t indicate whether they even tried to hold the drug companies accountable for the hardships their subjects have endured.

Despite their obviously earnest intentions to enlighten and create change, the directors also don’t tell their stories with a great deal of panache. “Off Label” often consists of a series of talking heads and generic footage of pills being processed on assembly lines. These are inherently dramatic tales presented in such a dry manner, it nearly saps them of all their drama.