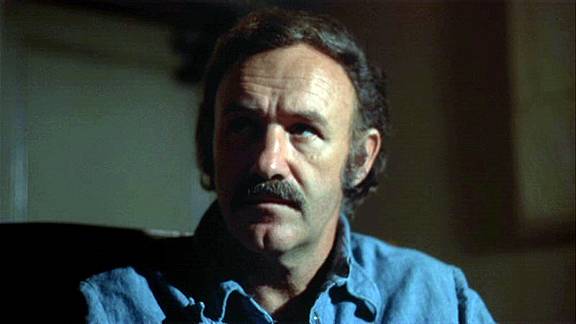

There’s some kind of irony in the release, so close together, of a movie that claims to be inspired by the detective novels of Ross Macdonald — but isn’t — and one that makes no claims but is a triumph in the Macdonald tradition. The first movie was the weary “The Drowning Pool,” in which Paul Newman gave one of his lesser performances. The second is Arthur Penn’s “Night Moves,” with Gene Hackman subtle and riveting as the private eye.

“Night Moves” is one of the best psychological thrillers in a long time, probably since “Don't Look Now.” It has an ending that comes not only as a complete surprise — which would be easy enough — but that also pulls everything together in a new way, one we hadn’t thought of before, one that’s almost unbearably poignant. The movie is the work of a master (Penn’s credits include “Bonnie and Clyde” and “Alice's Restaurant“), and yet because of an unhappy booking pattern it’s only in a handful of theaters. If you like private eyes, find it.

The eye this time is named Harry Moseby, perhaps with a nod toward Hackman’s great performance as Harry Caul in “The Conversation,” perhaps not. He’s a former pro football player and a man of considerable intelligence, whose wife (Susan Clark) runs an antique business. He’s a private detective for reasons, vaguely hinted at, involving his childhood.

A Hollywood divorcee, clinging to the last shreds of a glamor that once won her a movie director (and half the other men in town, she claims) hires him to trace down her missing daughter. Harry takes the case, pausing only long enough to track down his own missing wife — who is, it turns out, having a not especially important, affair with a man with a beach house in Malibu. His confrontation with the man, like so many scenes in the movie, is done with dialog so blunt in its truthfulness that the characters really do escape their genre.

Harry traces the missing girl to her stepfather, a genial pilot in the Florida Keys, and goes there to bring her back. And from the moment he sets eyes on the stepfather’s mistress, the movie, which has been absorbing anyway, really takes off. The mistress is played by a relatively unknown actress and sometime singer named Jennifer Warren, who has the cool gaze and air of competence and tawny hair of that girl in the Winston ads who smokes for pleasure and creates waves of longing in men from coast to coast. Miss Warren creates a character so refreshingly eccentric, so sexy in such an unusual way, that it’s all the movie can do to get past her without stopping to admire. But it does.

The plot involves former and present lovers of the girl and her mother, sunken treasure (yes, sunken treasure), conflicts across the generations and murders more complex by far than they seem at first.

These are all the trademarks of the Lew Archer novels by Ross MacDonald especially the little-girl-lost theme, and Alan Sharp’s screenplay uses them infinitely better than “The Drowning Pool” did — even though that was actually based on a Macdonald book. By the movie’s end, and especially during its last shock of recognition, we’ve been through a wringer. Art this isn’t. But does it work as a thriller? Yes. It works as about two thrillers.