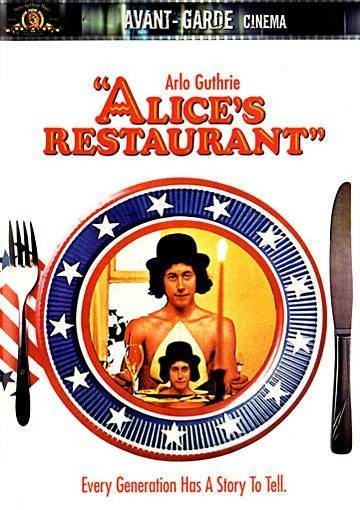

Arthur Penn’s “Alice’s Restaurant” is good work in a minor key. It isn’t a great film, but you never get the feeling that it wanted to be. You sense that Penn achieved what he set out to do: to make a relaxed, unstudied portrait of some friends, and some months in their lives, and some births, deaths and marriages.

To this degree he has been faithful to the spirit of Arlo Guthrie‘s original recording. A higher-pressure film would have been inappropriate. You almost wish, in fact, that the rudimentary thrusts toward a plot had been left out. “Alice’s Restaurant” is at its best when Arlo is on the road, going to college, hitchhiking, playing his guitar, getting drafted, taking his Army physical, going to see his friends Ray and Alice and things like that.

But it’s not as relaxed, and not as confident, in some awkward scenes involving Alice’s love life and her relationship with Ray. I guess Alice (played by the appealing Pat Quinn) is an Earth Mother. She folds lost souls to her bosom and tries for a transfusion of life force. Sometimes she succeeds. And to this degree she exudes a healthy sensuality, a generous spirit.

But then Ray keeps turning up, and they fight, and their relationship becomes ambiguous. What are we supposed to think? That she’s two-timing him? What does Ray think, for that matter? Penn doesn’t make it clear, and as a result the love scenes aren’t as positive as they should be.

There’s also a difficulty, for me at least, in the decision to bring Arlo’s father Woody into the film as a character. Woody, played by Joseph Boley, is shown in the last stages of the nerve disorder Arlo may develop someday himself. This is uncomfortably close to life, but we’re willing to accept it as part of the film’s fundamental honesty.

But the scenes themselves are not handled very well. Woody nods and tries to smile, and Arlo and his mother visit the bedside, and one afternoon Pete Seeger comes to play for his friend. But it’s all too staged, somehow. You know they were trying to do the scenes about Woody quietly and tastefully, but still you feel uneasy about it.

These are minor objections, however. For the most part “Alice’s Restaurant” is a warm and alive film. You can feel Penn trying to portray a life style rather than a plot with characters in it. He wants to express the spirit of the church Alice and Ray lived in, and the community they presided over. And he does it pretty well; we are reminded of some of the gentle scenes in “Bonnie and Clyde,” like the one in the Okie camp, and the time in the gas station when they meet C. W. Moss. This is a new feeling in American movies; it’s good to have it.

It is also good to have Arlo Guthrie himself, who is quiet and open and good on camera. His camera presence is so natural, in fact, that it contrasts with the tightness of some of the professional actors (especially James Broderick as Ray). “Alice’s Restaurant” finally becomes a synthesis of Arlo’s spirit and Arthur Penn’s tact.