It simply won’t do to call filmmaker Frederick Wiseman a documentarian. Even film critics and film lovers who normally aren’t all that actively/avidly enthusiastic about the documentary feature as a form—and I have to admit, I’m one of them—have to give it up for Wiseman. Like the Maysles brothers, like Shirley Clarke, like D.A. Pennebaker at his heights, Wiseman has created a body of work that proves him a great filmmaker, period. His latest picture, “National Gallery,” is a typically lucid, graceful and unobtrusively multi-tiered work.

The movie opens with a considered series of shots of paintings that hang in the London art museum that gives the film its title. While not a small museum, the National Gallery isn’t on a scale like that of New York’s Metropolitan or Paris’s Louvre and hence its focus is a bit narrower; the place displays paintings dating from the 14th Century to the end of the 19th. So immediately, as we perhaps recognize a Holbein or Rembrandt in the opening shots of the film, the movie draws us into an older world. But a familiar sound begins to break the silence that would create the ideal mood for contemplating these works? What is it? It gets louder, and soon Wiseman cuts to a wider shot of one of the gallery’s hanging rooms, and there’s a fellow operating a floor polisher.

This opening is a near-perfect encapsulation of Wiseman’s method. His camerawork is as objective, or as “objective,” as it gets; he’s really the only filmmaker of his gender who could set a documentary entirely in a strip club (his 2012 “Crazy Horse”) without running the risk of indulging a “male gaze.” Where he editorializes, or makes a point of declining to editorialize, is in his cutting. The opening invites the viewer into the realm of the sublime, then drops the viewer into the realm of the quotidian. This juxtaposition, Wiseman suggests, is a part of what makes the Gallery a noble institution.

Over the course of the movie, Wiseman takes us inside all of the activities that define this glorious space. There are shots of docents giving very lively and informed talks about art history and the different way art, particularly religious art, functioned in centuries past: “The painting would be acting as a sacramental channel,” explains one scholar. There is a meeting in which the head of the gallery, the lanky art historian Nicholas Penny, balks at the suggestion of using the façade of the gallery as a space for video projection of the London marathon. A colleague says that as the marathon will end in Trafalgar Square, there’s an inevitability to the Gallery’s presence in the coverage of the event. Penny, though thoughtful and understated, has clearly had it up to his neck with commercial considerations of a certain kind: “It’s gonna happen anyway so we should just use it then,” is not, he states forcefully, an argument that cuts much ice with him.

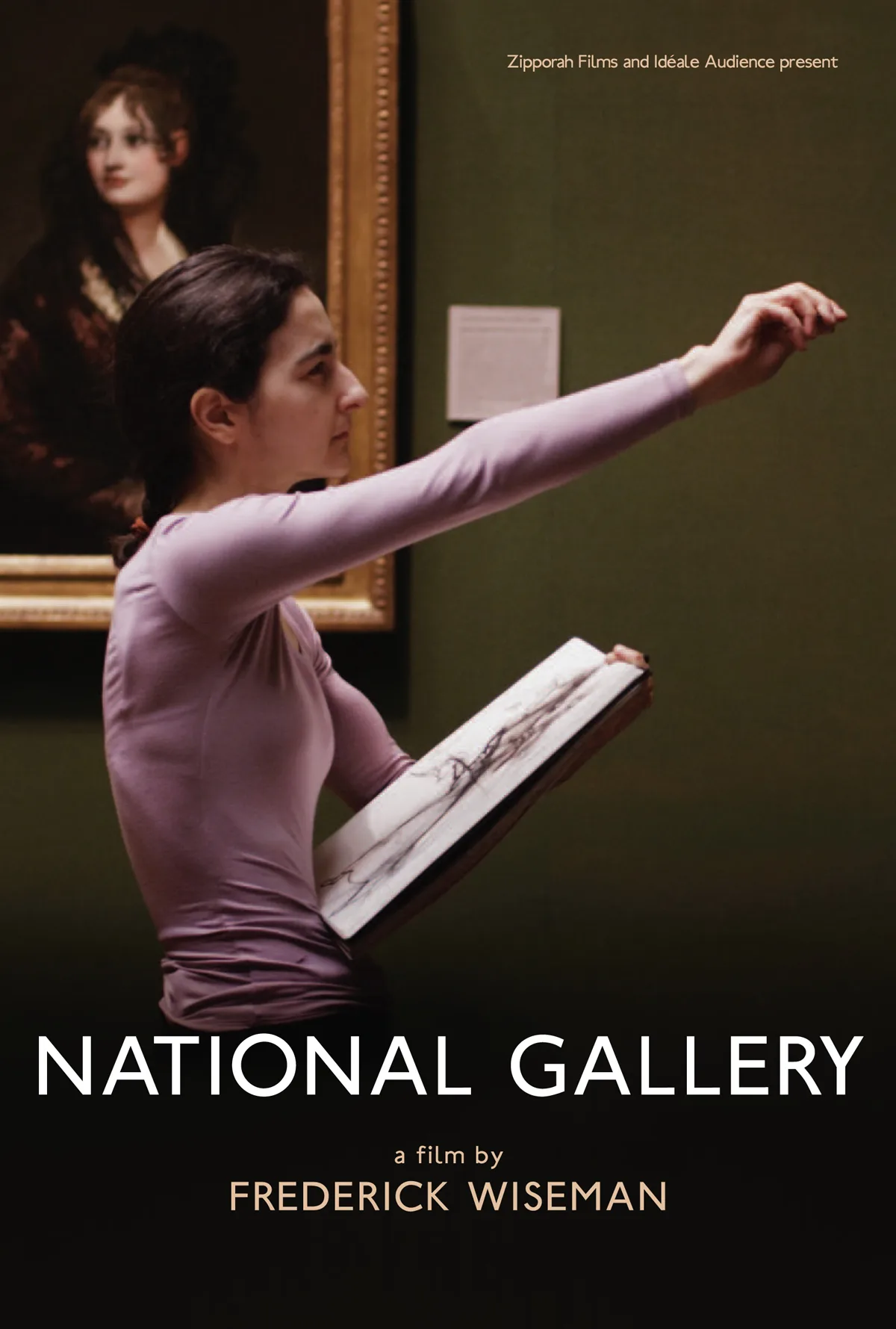

Also depicted: Life drawing classes, repairing damaged art, budget meetings, concern over frame shadows in the display of a triptych, and more. About midway through the picture, we see some Greenpeace activists rappelling down from the roof of the gallery, hanging a large protest banner. More narratively-inclined documentary directors—I’m thinking of the Maysles—would have spent some time focusing on the aftermath of the event. Wiseman shows it and moves on. It’s just something that happened, something that happens, and speed bumps and such don’t really figure that much in the day to day operation of such a place. The staff goes on, the lectures go on—Penny himself gives an interesting talk of Caravaggio’s “Boy Bitten By A Lizard”—and the incredibly absorbing three-hour film ends on a grace note that doesn’t so much affirm the permanence of art as it celebrates the nobility of perpetuating and preserving art.