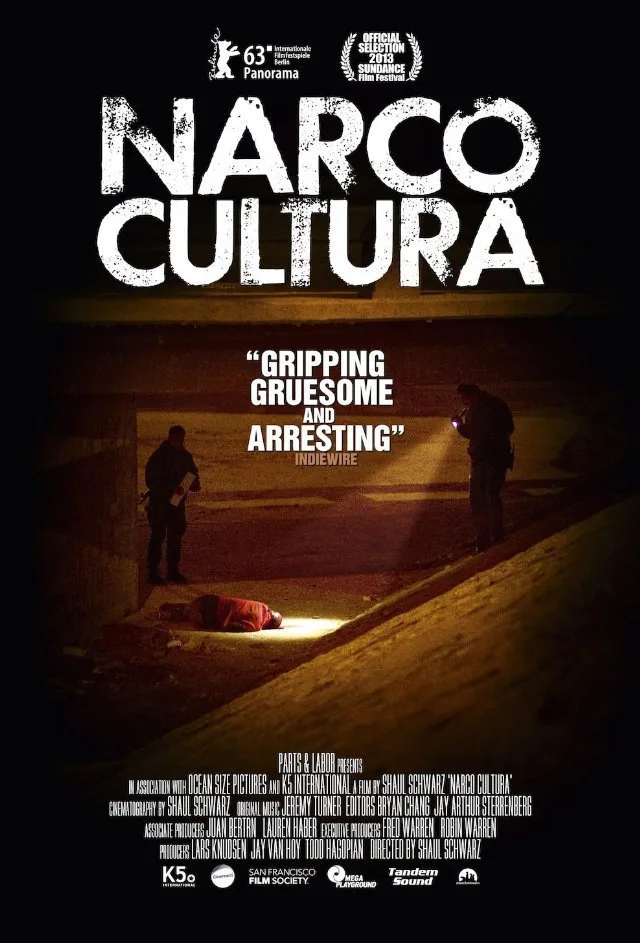

The narcocorrido is a Mexican style of ballad that draws from mariachi, blues and country music elements, with a tempo and accordion accompaniment straight out of polka. It’s a strange brew. Stranger still are the lyrics, which find melodious ways to exalt violent, ruthless drug dealers, the kind who assassinate cops and decapitate snitches. Actual drug trafficking gangs often commission the songs, both inspiring and taking inspiration from their grisly lyrics. In the documentary “Narco Cultura” narcocorrido producers and musicians brag that their folksy genre is about to become “the next hip hop,” a popular form born in the dreams and frustrations of poor people. The narcocorrido has corralled legions of fans in America.

The film profiles Edgar Quintero, an American singer whose handsome chubbiness and homicidal lyrics reminded me of (to keep the nascent-hip hop comparisons going) young Ice Cube but whose humble, ingratiating demeanor is more Young MC or Will Smith. Why is this happily married father of an infant selling murder music? Maybe because that music furnishes the modest but comfortable suburban lifestyle he enjoys in Los Angeles.

That’s the story throughout “Narco Cultura”: folks profiting from the music let the marketplace smooth over any moral conundrums. The songs themselves also semi-acquit the genre because they’re clever and self-aware. Pop music history is full of beautiful ballads about poisonous subjects. Country and blues legends boast a high lyrical body count, with a wink and a nod. Violent imagery can be metaphorical and cathartic. It’s the intensity of the ideas and emotions driving the violence that matter, and in the narcocorrido, as in rap music, the template is the American Dream as interpreted by Al Pacino’s Tony Montana. The 1980’s cocaine empire saga “Scarface” was a “Star Wars” for three decades of real-life Tonys who yearned to blast out of poverty as quickly as possible and knew minimum wage was just another trap. Yet “Narco Cultura” shows this underclass success formula of ruthless gain to be a fantasy far more vaporous than anything in “Star Wars”.

A dizzying range of patrons and clientele support boyish Edgar and his more hardened collaborators, from drug dealers to American radio stations to Walmart to exploitation filmmakers. Business is booming. Hordes of women swoon at the sight of narcocorrido singers, with their ammo belts, assault rifles and designer shades.

The way the film balances expose, visual poetry and lucid analysis of two economies (the drug trade, the music business) and two bureaucracies (law enforcement, media) in two countries (Mexico, the U.S.) is to be studied. Director-cinematographer Saul Schwarz doesn’t let any one element overwhelm the symphony or obscure his clearly despairing perspective. The visual style is that of a moody thriller, something I recently criticized the documentary “Dirty Wars” for indulging with a heavy hand. Schwarz’s hand is light and gracefully articulated even in moments that go right for the gut.

Present for many such moments is the film’s other leading man, CSI investigator Richi Soto. Richi’s beat and hometown happens to be the epicenter of Mexico’s drug war, Juarez, Mexico. He refuses to leave, even as the death toll rises absurdly and his colleagues keep falling to cartel assassins on their way home from work. His reasons are partly sentimental (expressed softly in voiceover narration), partly practical (investigating drug war murders is one of the few “good” jobs left). The film intercuts Soto’s investigations and Quintero’s rise in the narcocorrido world. Hollywood premieres and sold out concerts share screen time with gruesome autopsies and mothers of cartel victims wailing behind police tape. Schwarz’s instinct for light and composition give his cinema verite the punch of a great graphic novel. Editors Bryan Chang and Jay Arthur Sterrenberg assemble these images with efficiency that doesn’t undercut the content’s resonance—a righteous slickness.

At the film’s heart is a piece of bracingly un-slick found footage not shot by Schwarz that stops the movie cold. A mother’s sustained cry of anguish and anger at the Mexican government for how easily it writes off Juarez’s poor as collateral damage in the drug war, and at the citizens themselves for displaying the kind of complacency Martin Niemoller knew something about. After that, the film becomes at once more prayerful and suspenseful.That’s when soft-spoken and wise newspaper reporter Sandra Rodriguez steps in, like some kind of journalistic angel, to crystallize the dilemma as a cultural and political assisted suicide.

At what point do we stop writing atrocities off as a means to an end? Where do we draw the line regarding what’s best for our own families and what poisons the well for all families? What ultimate good is an economy whose primary engine is denial and blind social climbing? “Narco Cultura” wrestles with these questions without forgetting to keep its embracing eyes open for incidents that in lesser films would be called entertainment or comic relief. The people in this documentary are beautiful, funny, flawed, desperate, intelligent, deluded… In other words, it never forgets that these are questions for all of us. Just over the Mexico/U.S. border from Juarez is El Paso, Texas, ranked the safest large city in America three years in a row now. The question that that fact begs is in part why this film is a quietly subversive masterpiece.