The compelling artist profile doc “Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV” plays like a non-fiction biography that is also an art history primer. More detailed critical or historical context might have enhanced director Amanda Kim’s already informative and loving portrait of Korean video artist Nam June Paik. But there’s so much in Kim’s movie—especially in actor Steven Yeun’s voiceover narration and talking head interviews with Paik’s colleagues and contemporaries—that this account of Paik’s working life still resonates.

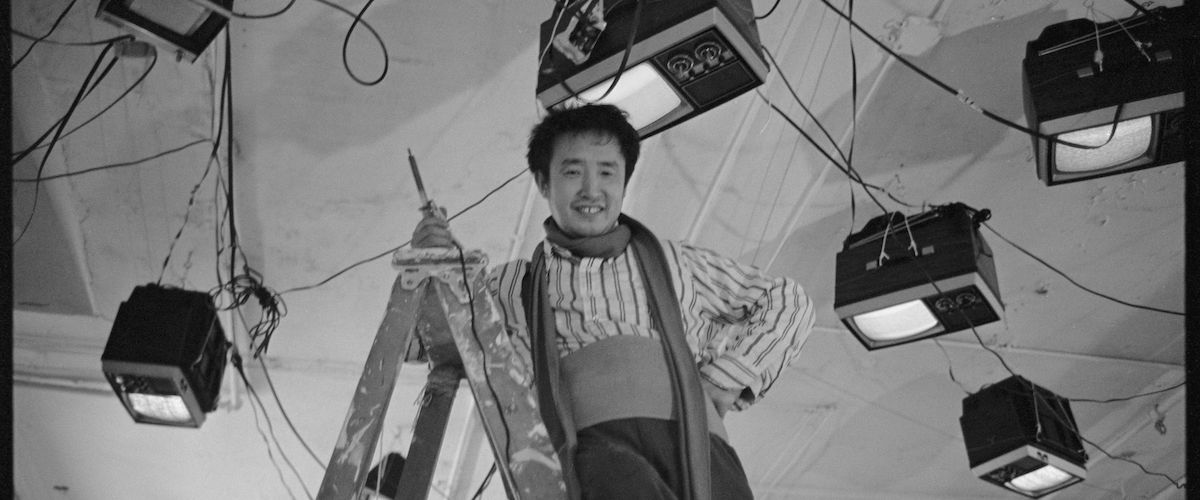

We follow the artist’s progress, starting as a misunderstood and, to some extent, willfully elusive action composer, then continuing as a prolific mixed-media pioneer. A wealth of documentary footage represents Paik and his work as an open question, leaving viewers to puzzle over the meaning and consequences of his performances and gallery installations, especially Paik’s now iconic work with old cathode ray tube (CRT) television sets. Kim’s engrossing character study illustrates how Paik developed a cohesive and still thrilling body of work using his uniquely exploratory methods, deceptively simple ideas, and Utopian ideals. And by leaving viewers wanting more, Kim also pays a fitting tribute to the mercurial Paik.

“Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV” begins with a considerate and fairly exhaustive defense of Paik’s earliest work, particularly his John Cage-inspired performance art pieces. Paik was a polyglot, a Hegelian, and a scholar of pre-renaissance music, for which he had a Ph.D. When he performed at Mary Bauermeister’s makeshift Cologne salon in 1961, Paik attacked a piano, clipped Cage’s tie with scissors, and threw shampoo on his mentor’s head. Paik then fled the building, telephoning a half hour later to say: the concert is over.

Bauermeister provides some intriguing commentary, and so does protean saxophonist Peter Brotzmann, who confesses that Paik was the only Asian artist he knew in the early 1960s, partly because of the “hidden colonialism” that’s intrinsic to the Eurocentric art scene. Still, the best and also perhaps least reliable source for information on Paik remains Paik. Kim supplements a wealth of video recordings of the artist with Yeun’s muted reading of Paik’s correspondence, interviews, and other writings.

In a mix of epigrammatic soundbites and testimonials, Paik describes the difficulties he had in finding opportunities and receptive audiences for his earliest work. Challenging live performances, like when cellist Charlotte Moorman played improvised instruments, sometimes wearing a Paik-designed brassiere with mini-TV monitor pasties, were also not immediately praised by art critics. That doesn’t necessarily make those earlier pieces misunderstood or great, but these early scenes in Kim’s movie do provide a foundational understanding of Paik and his values.

In television, Paik found a surprisingly accommodating medium for experimentation. Using magnets, portable cameras, and a plethora of CRT sets, Paik tested the plasticity of what he saw as an oppressive, one-way form of mass communication. Before the Internet became a staple of modern life, Paik used singular happenings, exhibitions, and installations to suggest a playful alternative to TV’s hegemonic reality.

Kim sparingly highlights Paik’s collaborations with contemporaries like Joseph Beuys and Merce Cunningham. Her focus often reflects the individualistic values that defined Paik’s work, as well as the sheer range of his social influences, including sponsorship by the avant garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas as well as long-time champion David Ross, a former curator at ICA and SFMoMA. Paik’s work was eventually celebrated internationally at The Guggenheim, The Tate Modern, and The Whitney, among others. He would later be embraced by representatives of his home country, though Kim wisely notes that this acknowledgment only came retrospectively and with some trepidation from Paik himself.

Kim’s non-fiction celebration of Paik is maybe a little too good at reflecting its subject’s teasing genius. Some intriguing claims are made about Paik and his vibrant work, like “Global Groove,” a boundary-pushing 1973 TV broadcast and multidisciplinary artists’ showcase, where performers like Cunningham and Moorman play within hyper-compartmentalized frames inside the camera’s frame.

Some talking head experts—many of whom worked with Paik—suggest that his influence was an obvious influence on everybody from Al Gore to Prince. That’s probably true, but these claims aren’t as compelling as well-measured interpretations of Paik’s work or divergent accounts of his variable successes, like when George Plimpton got trashed live on TV during “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell,” the internationally broadcast 1984 New Year’s Eve “installation” broadcast, whose participants included Laurie Anderson and a very stoned Allen Ginsberg.

“Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV” also works better as a movie than an illustrated article, a basic but deceptively tricky test failed by many profiles about unknown artists. The raucous effect and provocative impact of Paik’s work can be described and even successfully accounted for in writing. But you have to see it move to get a clear picture of the artist as a joyfully disruptive presence.

Now playing in select theaters.