Consider now Leelee Sobieski, who is 19 years old and has been acting since she was 12. “My First Mister” is the latest in a series of wonderful performances in a career so busy that earlier in 2001 she appeared in “The Glass House” and “Joy Ride” (which opened only a week ago). I did not much notice her in “Deep Impact” (1998) and wanted to avert my eyes from the entire movie during “Jungle2Jungle” (1997). But in 1998 she came into her own as the heroine of “A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries,” based on the autobiographical story by Kaylie Jones, the daughter of the novelist James Jones. And in 1999 she found time to be Joan of Arc on TV, co-star with Drew Barrymore in “Never Been Kissed,” and play a small role in Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut.” A new star doesn’t always explode. Sometimes she just … occurs to you. I was so involved in the story of “A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries” that my review said nothing specific about her performance, although in a sense the whole review was in praise of it. Only with “Glass House” and “Joy Ride,” seen so close to each other, with the memory of “My First Mister” still warm from Sundance 2001, did it become inescapable that she is an important new talent, an actress who has arrived at the top without having to make a single teenage horror film or “American Pie” ripoff.

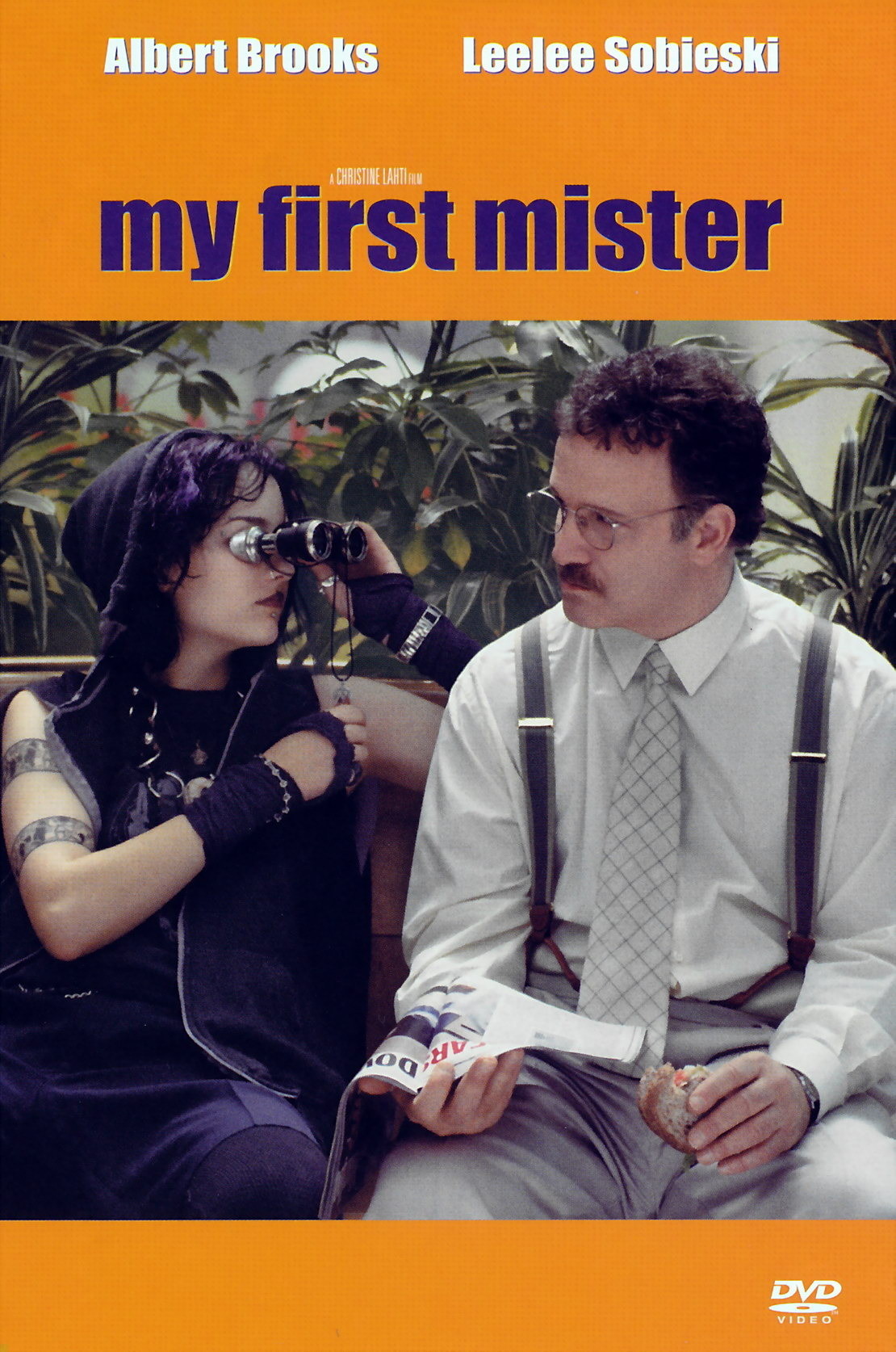

She usually plays intelligent, well-scrubbed characters, convincingly. Here she’s Jennifer, smart but alienated–a pierced, tattooed goth. Stomping around in zip-up boots, her chains clanking, she is the despair of a ditzy mother (Carol Kane) who thinks the answer to everything is getting dinner on the table on time. She has refused to go to college, has no job or boyfriend, is a loner wandering through the mall–and one day sees a man adjusting the window display at a men’s clothing store. Something about his personal style, his manner of carrying himself, strikes her, and she drifts in to ask about a job.

This is Randall (Albert Brooks). “Hire you?” he says. “For every suit you sell, you’re gonna send 30 customers fleeing out of the store.” “Dress me,” she says. He does. “I look like a Republican,” she says. He’s 49, she’s 17. It’s odd how they become friends while tacitly sidestepping the idea of sex, although she does raise the subject once, so bluntly that he sprays his Sanka at a hip coffee shop.

The movie is not about sex, not about a Lolita, but about a friendship between two loners. He has her number. “Do you have a copy of The Bell Jar next to your bed?” he asks. It’s a good guess. “Who do you talk to? Who are your friends?” he asks. “You,” she says.

These two characters are so particular and sympathetic that the whole movie could simply observe them. In a way, I wish it had. The film, directed by Christine Lahti from a screenplay by Jill Franklyn, is best in the first hour or more, when things seem to be happening spontaneously. I was a little disappointed when it narrowed down into more conventional channels, involving a crisis and a long-lost son. And a closing dinner scene, assembling the characters, seemed like a convenient plot device. Still, Sobieski and Brooks stay true to their characters even as the movie gives them less room for spontaneity. Brooks is always able to enrich a role with specific, precise touches. Watch him straightening the stacks of magazines in his house, and listen to him tell a tattoo artist, “I want the smallest tattoo you have. Can you give me a dot, or a period?” Sobieski is wise to make Jennifer practical in the way she abandons her lifestyle: Instead of making it seem like a corny transformation, she makes it a pragmatic choice. It works for her, and when it stops working, she ditches it.

The bravest thing about the movie is the way it doesn’t cave in to teenage multiplex demographics with another story about dumb adults and cool kids. “My First Mister” is about reaching out, about seeing the other person, about having something to say and being able to listen. So what if the ending is in autopilot? At least it’s a flight worth taking.

Note: There is no earthly reason this movie is rated R. The flywheels at the MPAA have taken flight from the values of the world we inhabit.