It’s an uncommon family, especially by the standards of Dijon, France, circa 1954. The father is a wealthy and successful physician. He is married to a girl 15 years younger than himself and, worse, the girl is Italian, which profoundly shocked his French bourgeois family at the time of the marriage. No matter. The union has been blessed with three sons, and at the time the movie opens the mother is closer to them (in age and temperament) than to the father.

The movie opens with a good-natured family tussle, and only after it’s over do we discover that Lea Massari is the mother. She looks more like an older sister, and she is certainly more of a pal than a mother to her children. The family discipline is administered by a very round, very muscular maid.

The two older sons are pranksters and brats, but the youngest is bookish and thoughtful. To be sure, his taste in reading runs to Henry Miller, de Sade and “The Story of O,” and his thoughts are of a nature to be dialogue for the confessional. But he’s a bright, quiet, likable kid. He is also at that sharp, poignant moment of midadolescence when it begins to seem that carnal knowledge is forever out of reach, but just barely.

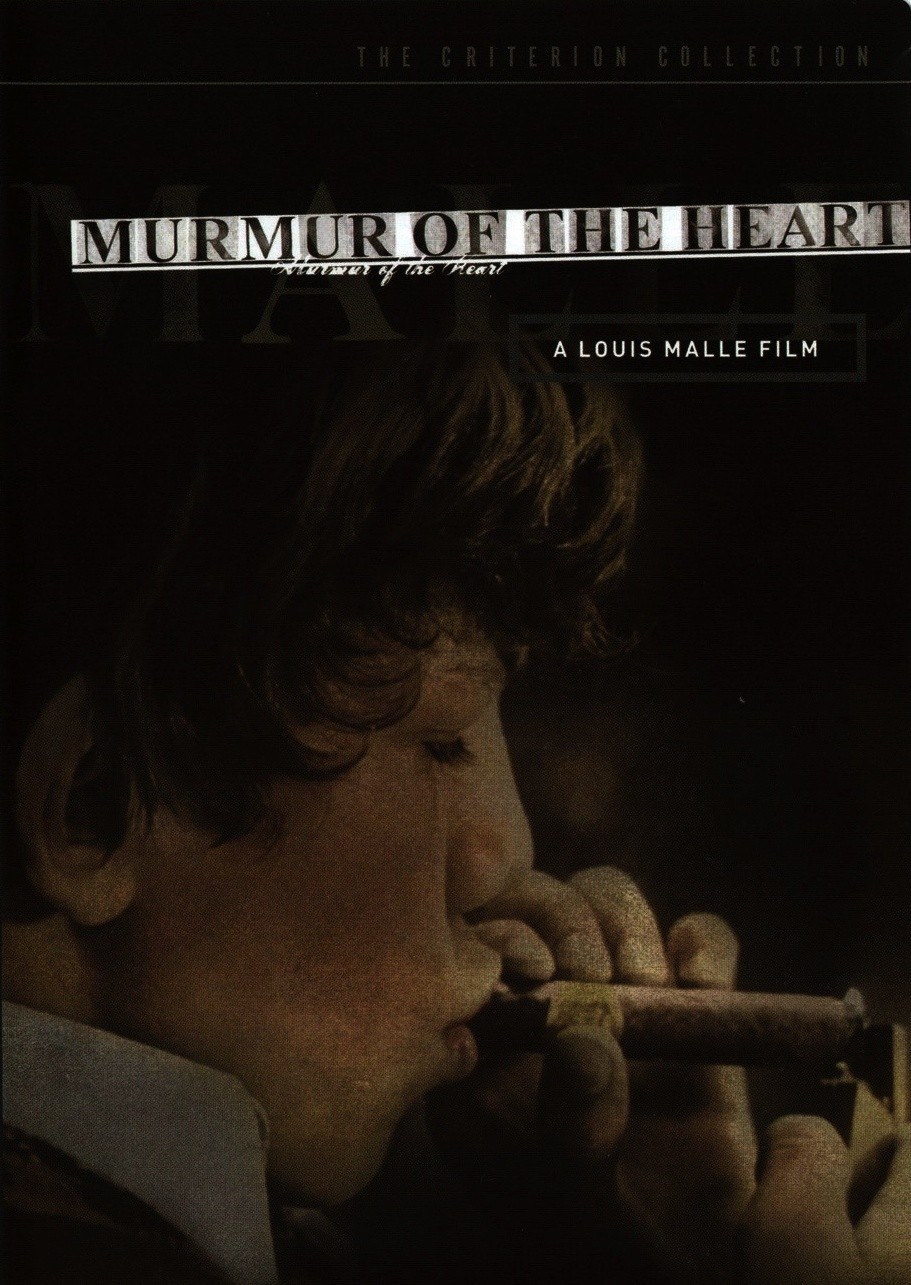

Malle gives us the family in a series of short, fairly self-contained scenes. There are fights and truces, and the boys learn to smoke cigars, drink brandy and forge paintings. The youngest son is taken by his brothers to a brothel (in order to be the victim of a cruel practical joke, as it turns out). The mother has an affair, not very discreetly. And then it turns out the young boy has a heart murmur. Summer at a resort is prescribed, and the mother goes along to keep her son company (and to continue her affair).

They take adjoining rooms at the resort hotel, and then Malle sets us up for the final scenes so skillfully that the moment of incest, when it occurs, seems almost natural, more fond than carnal, and not terribly significant. How he achieves this effect is beyond me; he takes the most highly charged subject matter you can imagine, and mutes it into simple affection.

The boy is played by a nonactor, Benoit Ferreux, whose puzzlement about growing up, and whose admiration at the possibilities of life, remind us of young Jean-Pierre Leaud in Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” of a decade ago. The two movies deserve comparison in more ways than one. And yet “Murmur of the Heart” isn’t really about the boy, but the mother. Lea Massari (you may remember her as the girl in “L'Avventura“) is so irrepressible, so irresponsible, so much a girl and not quite an adult, that her performance takes scenes that might have been embarrassing, and makes them simply magical.