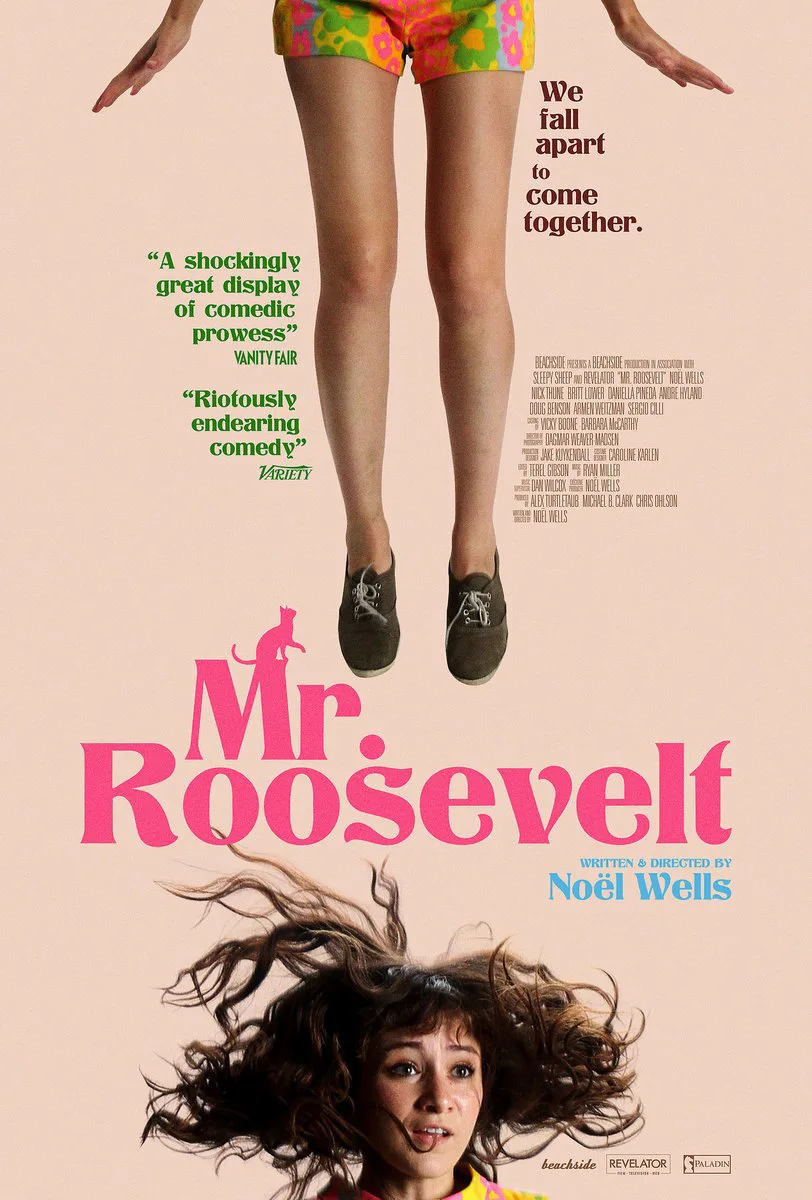

Emily Martin (Noël Wells) doesn’t quite know how to explain what it is she does, or even what it is she wants to do. She’s not exactly an actress. She’s not exactly a comedian either. She hangs around improv clubs in Los Angeles, but feels put off by the whole “scene.” She made one YouTube video that went viral, but she couldn’t “monetize” it. Emily is first shown during an audition in which she transforms herself in quick succession since she only has five minutes, into Holly Hunter at a garage sale, Kristen Wiig coming across a murder, a Vine video of someone tripping at a Beyonce concert, and a “girl who’s always cold.” The casting director is frozen in fear at the rollicking manic display. Emily tromps off to her gig editing videos in some random apartment crowded with people on laptops. All of this occurs in the first five minutes of Wells’ first feature as a writer and director, “Mr. Roosevelt.” Anyone who has ever circulated, even peripherally, in any comedy club scene, will recognize all of it. It’s a quick-flash study of both frenzied activity and crushing ennui.

Emily is a transplant to Los Angeles from Austin, Texas. She is unmoored. The “industry” has no idea what to do with someone like her. She doesn’t know what to do, and her awkward self-deprecation makes others recoil from her. When her ex-boyfriend Eric (Nick Thune) calls to let her know that her cat—Mr. Roosevelt—has died, Emily dissolves into tears and books the first flight back to Austin she can find.

Wells is an established actress and writer. With a recurring role on “Master of None,” and a brief stint on “Saturday Night Live,” she also recently played Jessica Williams’ best friend in “The Incredible Jessica James,” and was funny support staff to the lead. In her first film as a writer-director, she presents a world she clearly knows well. From Texas originally, Wells filmed “Mr. Roosevelt” around Austin, with the clear familiarity of a local. Austin residents will probably pick up more of her commentary than outsiders, but it’s clear what she’s getting at when she shows Emily’s disappointment at the closing of her favorite coffee shop. Austin is gentrifying. Wells has been very smart in creating the lead character, both in the writing, and the performing. She presents Emily in broad strokes at first—the audition, a one-night stand with a guy who never puts down his phone (even when her head is in his crotch), her free-floating ambition for a career—but much of it works by stealth. You have to put it together as you go. Wells herself is very endearing as a personality, so it takes a while to really “get” that Emily is kind of a nightmare. For example, she arrives in Austin with just a backpack, having made no arrangements for where she will stay. She clearly assumes she will stay with her ex in the house where they once lived together, even though he is involved in a brand-new relationship. This is a woman who does not have her act together. Over the course of the film, her nonexistent “act” will deteriorate even further, as she thrashes about in jealousy at her ex’s perfect new girlfriend, bristles at questions about her life in Los Angeles, and ratchets up her competitive mourning for the aforementioned cat Mr. Roosevelt. It’s not that Emily is not likable. It’s that she’s a mess. Being a mess is extremely human.

Eric’s new girlfriend is the kind of woman designed to make insecure women feel worse. She is, as Emily complains, a “Pinterest board come to life.” Celeste, played by Britt Lower with impenetrable calm that also manages to be very funny, is an “entrepreneur,” equally handy with whipping up mimosas and whipping out a drill. Eric—once a musician—is now studying to get his real estate license. Emily compliments Eric on a shirt he’s wearing and he replies, “It’s breathable cotton.” He drinks oolong tea now. Emily is horrified. She doesn’t even know who he is anymore. At a disastrous group dinner at a restaurant, Emily meets Jen (the wonderful Daniella Pineda) while having a private freakout in the bathroom, and Jen matter-of-factly throws a glass of water in Emily’s face to snap her out of hysteria. It’s the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

The premise of “Mr. Roosevelt” is pretty slight, but it’s filled with funny performances and biting snippets of social commentary. There’s a really well-done sequence—the most evocative in the film—where Emily hangs out with Jen and her friends at a watering hole, and they get stoned and all take their tops off (“It’s legal here,” someone drawls) and do cannon balls into the water, or tiptoe across the rocks in an awkward kick-line. The nudity is playful, innocent, and captures Austin—its essence and vibe, a vibe Wells clearly loves. Emily’s behavior leads her on a collision course with Celeste, with Eric, with her own life, and even with Jen, who constantly has a glass of water at the ready should Emily ratchet it up again.

Wells has given us a personal and extremely observant story, with moments of honesty and humor. She is fair to every character. Even Celeste ends up being multi-layered. Wells is a talented writer and has woven together the strands into a humorous whole. The film could have been choppily episodic, or had the unfortunate structure of sketched-in “bits” unconnected to a narrative. Instead, it’s a funny story about a funny woman who finally realizes it’s time to grow up.

It is a “win” for women in film when one of the biggest blockbusters of the year, and a “superhero comic book movie” no less, is directed by a woman. Patty Jenkins, in directing “Wonder Woman,” has broken through a certain glass ceiling. When I interviewed director/cinematographer Reed Morano in 2015 about her first feature, “Meadowland,” I asked her about the challenges faced by female directors in the industry, and she said, “Isn’t it weird that this male director who has only directed a $2 million dollar Sundance movie is now suddenly directing a hundred-million-dollar Marvel movie, for his second film? And you definitely don’t see happen that with women. There’s a discrepancy there.” But while it’s great to see women move into bigger budget film-making, it’s even more important that women create their own stories, do what they want to do. I would hate to see the equation Blockbuster = Success. The more women develop their own projects, produce their own films, make films their way, telling the stories they want to tell, the healthier the industry will be. Wells’ “Mr. Roosevelt” is part of that.