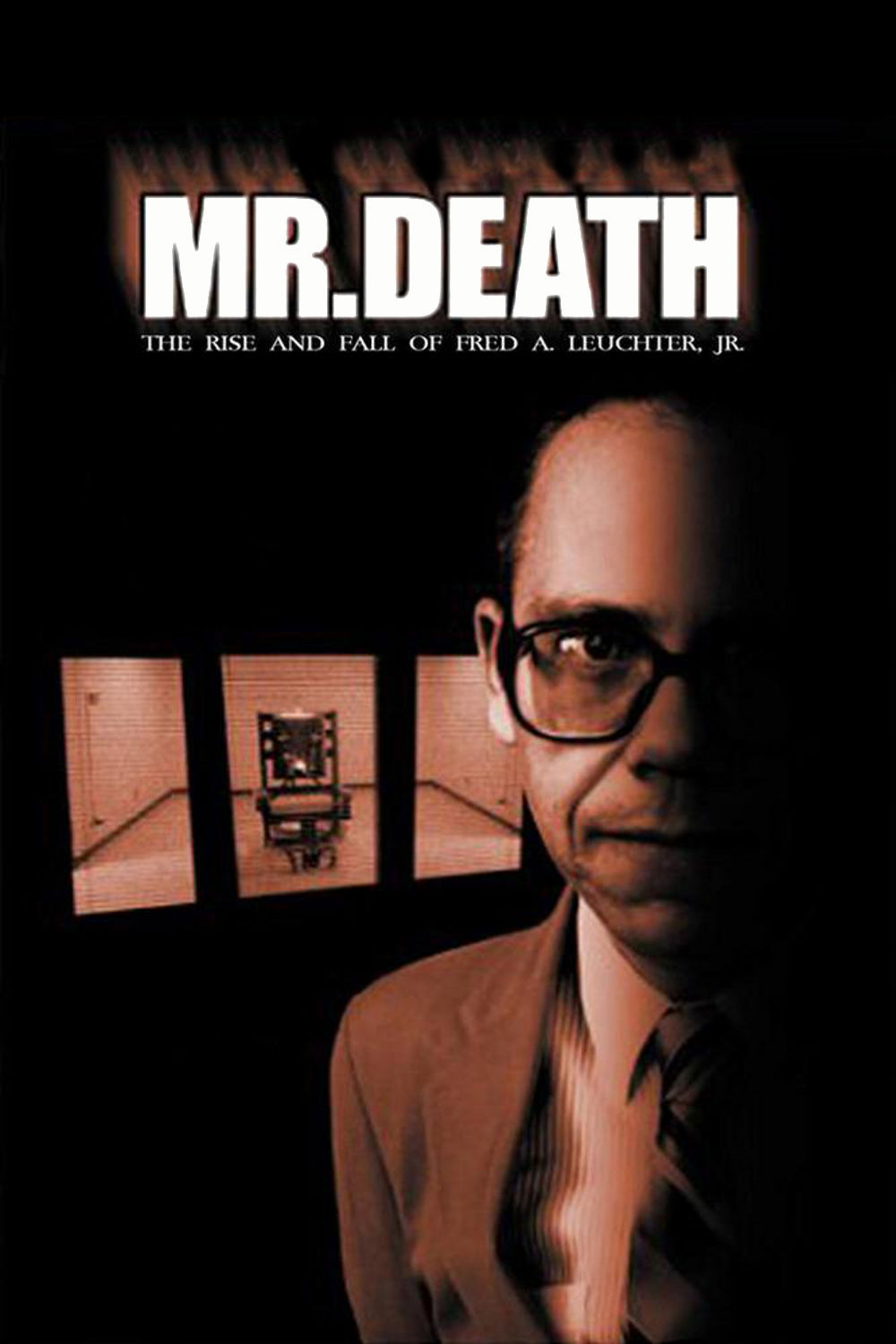

The hangman has no friends. That truth, I think, is the key to understanding Fred A. Leuchter Jr., a man who built up a nice little business designing Death Row machines, and then lost it when he became a star on the Holocaust denial circuit. Leuchter, the subject of Errol Morris’ documentary “Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter Jr.,” is a lonely man of limited insight who is grateful to be liked–even by Nazi apologists.

This is the seventh documentary by Morris, who combines dreamlike visual montages with music by Caleb Sampson to create a movie that is more reverie and meditation than reportage. Morris is drawn to subjects who try to control that which cannot be controlled–life and death. His heroes have included lion tamers, topiary gardeners, robot designers, wild turkey callers, autistics, Death Row inmates, pet cemetery owners and Stephen Hawking, whose mind leaps through space and time while his body slumps in a chair.

Fred Leuchter, the son of a prison warden, stumbled into the Death Row business more or less by accident. An engineer by training, he found himself inspired by the need for more efficient and “humane” execution devices. He’d seen electric chairs that cooked their occupants without killing them, poison gas chambers that were a threat to the witnesses, gallows not correctly adjusted to break a neck. He went to work designing better chairs, trapdoors and lethal injection machines, and soon (his trade not being commonplace) was being consulted by prisons all over the United States.

Despite his success in business, he was not, we gather, terrifically popular. How many women want to date a guy who can chat about the dangers of being accidentally electrocuted while standing in the pool of urine around a recently used electric chair? He does eventually marry a waitress he meets in a doughnut shop; indeed, given his habit of 40 to 60 cups of coffee a day, he must have met a lot of waitresses. We hear her offscreen voice as she describes their brief marriage and demurs at Fred’s notion that their visit to Auschwitz was a honeymoon (she had to wait in a cold car, serving as a lookout for guards).

Leuchter’s trip to Auschwitz was the turning point in his career. He was asked by Ernst Zundel, a neo-Nazi and Holocaust denier, to be an expert witness at his trial in Canada. Zundel financed Leuchter’s 1988 trip to Auschwitz, during which he chopped off bits of brick and mortar in areas said to be gas chambers and had them analyzed for cyanide residue. His conclusion: The chambers never contained gas. The “Leuchter Report” has since been widely quoted by those who deny that the Holocaust took place.

There is a flaw in his science, however. The laboratory technician who tested the samples for Leuchter was later startled to discover the use being made of his findings. Cyanide would penetrate bricks only to the depth of one-tenth of a human hair, he says. By breaking off large chunks and pulverizing them, Leuchter had diluted his sample by 100,000 times, not even taking into account the 50 years of weathering that had passed. To find cyanide would have been a miracle.

No matter; Leuchter became a favorite after-dinner speaker on the neo-Nazi circuit, and the camera observes how his face lights up and his whole body seems to lean into applause, how happy he is to shake hands with his new friends. Other people might shy away from the pariah status of a Holocaust denier. The hangman is already a pariah and finds his friends where he can.

Just before “Mr. Death” was shown in a slightly different form at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival, a New Yorker magazine article by Mark Singer wondered whether the film would create sympathy for Leuchter and his fellow deniers. After all, here was a man who lost his wife and his livelihood in the name of a scientific quest. My feeling is that no filmmaker can be responsible for those unwilling or unable to view his film intelligently; anyone who leaves “Mr. Death” in agreement with Leuchter deserves to join him on the loony fringe.

What’s scary about the film is the way Leuchter is perfectly respectable up until the time the neo-Nazis get their hooks into him. Those who are appalled by the mass execution of human beings sometimes have no problem when the state executes them one at a time. You can even run for president after presiding over the busiest Death Row in U.S. history.

Early sequences in “Mr. Death” portray Leuchter as a humanitarian who protests that some electric chairs “cook the meat too much.” He dreams of a “lethal injection machine” designed like a dentist’s chair. The condemned could watch TV or listen to music while the poison works. What a lark. There is irony in the notion that many U.S. states could lavish tax dollars on this man’s inventions, only to put him out of work because of his unsavory connections. The ability of so many people to live comfortably with the idea of capital punishment is perhaps a clue to how so many Europeans were able to live with the idea of the Holocaust: Once you accept the notion that the state has the right to kill someone and the right to define what is a capital crime, aren’t you halfway there? Like all of Morris’ films, “Mr. Death” provides us with no comfortable place to stand. We often leave his documentaries not sure if he liked his subjects or was ridiculing them. He doesn’t make it easy for us with simple moral labels. Human beings, he argues, are fearsomely complex and can get their minds around very strange ideas indeed. Sometimes it is possible to hate the sin and love the sinner. Poor Fred. What a dope, what a dupe, what a lonely, silly man.