This review was originally published on August 19, 2016 and is being republished for Black Writers Week.

To be a black kid in America is to understand intimately and far too young what it means to be disregarded, politicized, isolated—all themes that thread their way through adolescence. To be a black kid from America living in Heidelberg, Germany is to only have those issues become impossible to ignore. This is the fertile ground on which “Morris From America” builds its sweet-hearted, somewhat slight, and detrimentally too eager-to-please coming-of-age tale. That more films don’t mine this fraught landscape is a travesty. Growing up is so often about trying on new identities until you grow more comfortable and figure out your own. For black kids it’s so much about the identities and misconceptions thrust upon them. Despite the film’s notable strengths, this is a careful distinction that writer/director Chad Hartigan misses, much to the film’s detriment.

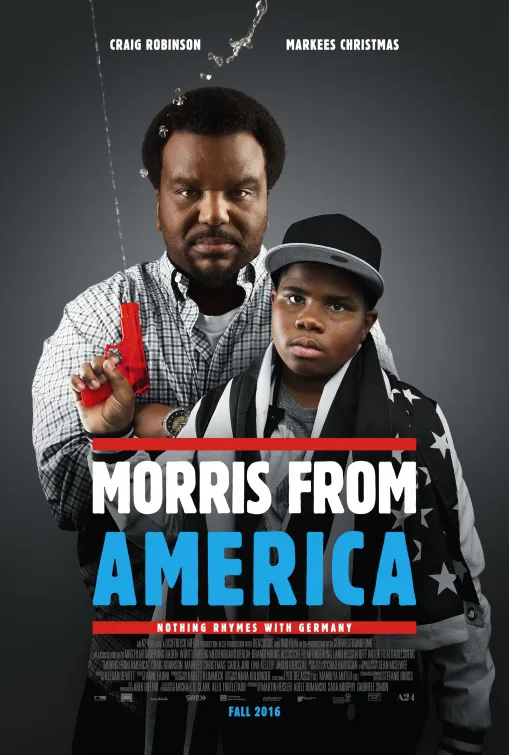

“Morris from America” centers on the title character (newcomer Markees Christmas) and his single dad, Chris (Craig Robinson) as they try to stick together in the isolating terrain of Heidelberg. They find a comfortable routine—getting ice cream, arguing over hip-hop, ignoring the weighty memory of Morris’ dead mother that hovers at the margins of their lives. But their strong relationship isn’t enough to fully satisfy their desire for connection and community. It’s here that the film truly finds its most interesting ground by touching on how loneliness shapes us.

“I don’t need any friends,” Morris says early on.

“Everyone needs friends,” his language tutor Inka (Carla Juri) assures.

Morris doesn’t have many options when it comes to friends and his time at a local youth center only makes that more clear. Morris and the kids around him are a study in contrasts. They’re thin blondes and redheads with none of his earnestness. They throw insulting nicknames at him like “Big Mac” and “Kobe Bryant” to remind him of his place in their world. He’s a dark-skinned, chubby, hip-hop head. But he ends up finding the closest thing to friendship in the 15-year old Katrin (Lina Keller), a winsome girl feigning womanhood through the usual mix of teenage rebellion.

“Morris from America” nails how even minor age differences in adolescence feel like lifetimes. Even before her motorcycle-riding, DJ boyfriend hits the scene, it’s clear Morris doesn’t have a chance and Katrin is just teasing him. But that just emboldens him more. There’s an easygoing charm to watching their friendship develop. Christmas and Keller have a chemistry that feels authentic to the sort of unrequited crush between them. But Katrin isn’t solace from the racism Morris faces elsewhere; if anything, she pushes it to the surface. She’s a bit too curious about his blackness asking about his love of rap, if black people can dance, and his “big black dick” in a particularly cringe worthy scene. Christmas’ performance elevates moments like these as he displays a mix of confusion, desire and embarrassment. He finds notes that the script and direction seem to bypass—calling attention to how the character’s loneliness and disconnect from the culture around him leads him to find weak approximations of what he’s truly yearning for. Although sometimes not even he can fix a rather misguided scene involving a pillow, Katrin’s sweater, and an explicit Miguel song.

Even with its keen understanding of the awkwardness of being a teenager, “Morris From America” ultimately has a cozy, comforting tone. Which is a problem. Adolescence has sharp edges to it—it can’t always be sweet and ultimately uplifting. The film’s desire to be a pleasing, saccharine story causes it to bungle the darker aspects of the story especially when it comes to race.

A knot grew tighter and tighter in my stomach as Morris leapt into one mistake after another fueled by the naïve hope of connecting deeper with Katrin. He soon trips into the sort of teenaged rebellion that defines much of Katrin’s identity: sketchy parties, drinking, light drug usage. Each of these scenes make Morris seem even younger than he looks. Hartigan wisely doesn’t veer into afterschool special territory even once Chris finds out. But there’s something missing here that I couldn’t ignore.

Every black kid growing up eventually hears the same set of guidelines about existing in the world. How even minor trouble can get you into the path of the police. And being in their path can get you killed. You have to toe the line in ways your white friends never even have to think about. You must be hyper-vigilant to prove your worth and stay out of trouble to survive. Morris acts like a kid who never got that conversation which seems less a narrative choice and more a blind spot of Hartigan’s as the film continues, especially as there are moments where his race is what gets him in trouble. I wasn’t expecting Chris to ever lay down some overwrought monologue about police brutality. This isn’t that kind of movie. But that he doesn’t say anything about the trouble Morris can find himself in feels emotionally and intellectually dishonest. Sure, we can chalk that up to Chris being a widower who perhaps feels uncomfortable with the weight of parenthood being all on his shoulders but the script doesn’t delve into that enough.

“Morris from America” is not the kind of film that stays with you, but its central performances do. Markees Christmas embodies the tender yearning that comes with adolescence hiding his vulnerability in a slack physicality as if he’s trying to seem even smaller to the world around him. But it’s Craig Robinson’s performance that truly gets under your skin. He demonstrates an incredible range in the film. He’s warm, funny, and brings the loneliness of his character into focus. Loneliness underscores his physical presence in the slope of his shoulders, the disappointment in his eyes, and how the character continues to wear his wedding ring. You can’t help but feel for him as the void his wife left behind becomes apparent in how he fails to connect with women and feels just as lost as his son.

But ultimately Hartigan’s film seems too eager to be uplifting and easygoing. Just when it’s about to hit a nerve it pulls back into more comfortable territory showing another slow motion sequence of Katrin’s hair whipping around her as Morris looks on awestruck. There’s a fascinating scene where Chris discovers some explicit lyrics Morris wrote thanks to the over-eagerness of Inka. The uneasiness and casual racism of the event is evident. Hartigan wisely lets us fill in the blanks in regards to the ugliness of this situation. But he utterly fails when Chris confronts Morris. Why does this 13-year old black kid whose father works on some minor soccer team write about a hard life full of sex and violence? The lyrics are a cliché of black masculinity and growing up poor that Morris knows nothing about, which Chris wastes no time telling him. While Robinson adds notes of anger and frustration to the confrontation, the script itself shortchanges a moment ripe with possibility. Why does Morris put up a front embodying the same stereotypes the German kids expect of him? Is this a defense mechanism or sincerely the kind of rapper he wants to grow up to be? These aren’t questions the film answers let alone considers in the first place. But the palpable yearning of its characters and the strength of the lead performances find grace and power where the rest of the film can’t.

“Any human touch can change you,” James Baldwin once wrote. In “Morris from America” this proves all too true.