“Monte Walsh” is as lovely a Western as I’ve seen in a long time. Like a lot of recent Westerns, it’s about the end of the old West. “Monte,” a friend says to Lee Marvin, “do you realize how many cowpunchers there were out here 10 years ago? Well there’s a hell of a lot less now. And no jobs for them.” And so Monte Walsh, 50ish, thinks in a rather disorganized way of getting into some other line of work and maybe even getting married.

The thing that helps make up his mind for him is when his best friend Chet (Jack Palance) gives up cowpunching, moves into town and marries the “hardware widow.” Chet’s wedding starts Monte thinking about marrying the town whore (Jeanne Moreau), who has never taken a penny from him and who clearly loves him.

Times have been hard for her, too. Prostitution, she observes, is a profession of diminishing returns, and she has had to move to a railroad town nearby. With the consolidation of all the ranches into one big spread managed by some financial wizards from back East, jobs for cowboys have become scarce. And thus, inevitably, there has been less call for her services. Monte rides over to the railroad town and asks her what she thinks about the idea of getting married.

Moreau, in a moment of luminous acting, thinks it over and then smiles and says “I like it” in a way that can’t be described. Then she reflects: “Of course marriage is a common ambition in my profession.”

But not in Monte’s. “Cowboys don’t get married,” he observes to Chet. So he toys with the idea of stunt-riding for a Wild West show, but the thought of all those concrete cities without any open spaces is too much for him. And so he is faced, toward the end of the movie, with a very lonely desperation. This may be the first three-handkerchief Western.

There have been, I mentioned, several movies recently about the passing of the old West. They seem to be inspired by different kinds of motives. Some hands in Hollywood seem to believe that the Western itself is dead, that since you can’t seriously peddle the old good guy-bad guy plots, you have to dismantle them and bury them.

“The Wild Bunch” and “The Professionals,” each in its own way, were about the shortage of work for gunslingers. They suggested that violence had gone out of style in the West, that a gun on the hip was no longer required in polite society. “The Wild Bunch” seemed to seek death almost suicidally in the last half of that great movie: they’d lived by the gun and they had to die by it, ironically, because they knew no other way to make a living.

“Monte Walsh” is set at the same psychological moment in the West, but it takes a quieter and, on the whole, more thoughtful approach. There’s a fair amount of gunplay, yes, and Marvin has a well-staged action scene where he tries to tame a bronco and succeeds in destroying half a town. But mostly the movie sticks close to ordinary life: to the camaraderie of the bunkhouse and the range, to the everyday life of the working cowboy and to the shy and beautiful love between the cowboy and the prostitute. The movie is rough but it is almost always tender.

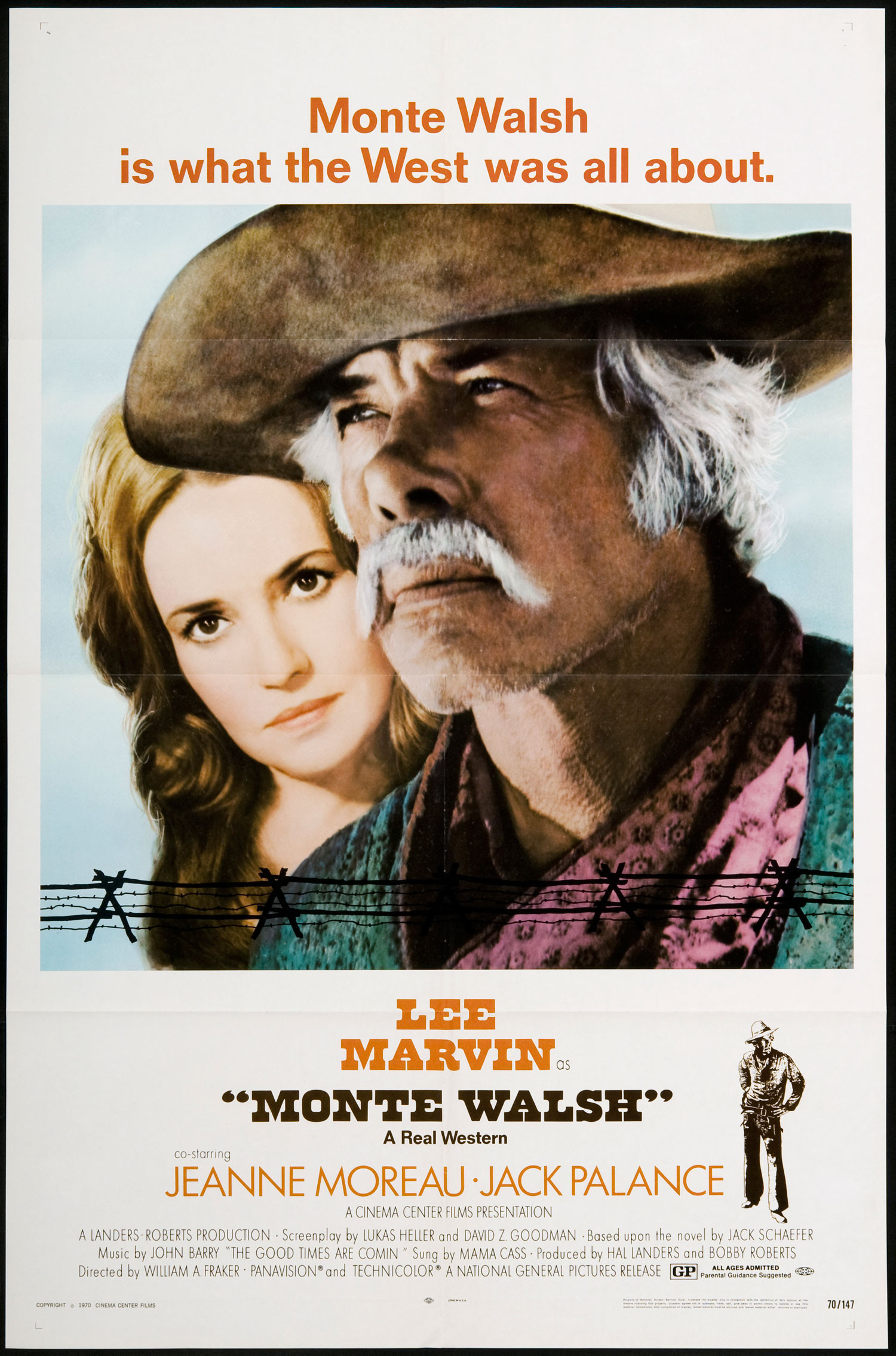

The performances are extraordinary. Marvin has very seldom been better; he leaves in the toughness of his usual screen character, but he also reveals a lot of depth. He’s often directed wastefully; directors want him for his presence and authority, but don’t really seem to want a performance from him. And he obliges, usually for lots of bread (“Paint Your Wagon” was a sad example). This time, he acts.

Miss Moreau and Palance both seem to relate to him especially well. Given their roles of lover and best buddy, there was a danger of clichés. But you never get that feeling; the scenes seem real. You’re reminded once again what a good actor Palance is, and how seldom he gets the opportunity to prove it.

A lot of the credit for the movie’s taste and emotional depth probably belongs to William Fraker, a talented cinematographer who was directing for the first time. Most first directors choose projects they wanted to make long before they got the opportunity. Fraker, whose credits include “Rosemary’s Baby,” photographed “Paint Your Wagon” and must have been thinking all during that unfortunate movie about bow he’d direct Marvin, if he got the chance. He did, and “Monte Walsh” was worth waiting for.