The wits out in Hollywood have their own names for “Mobsters,” like “The Godson” and “GoodlookingFellas.” They have a point. It does seem sort of strange, watching a movie about four gangsters in their 20s. We expect gangsters to be older, to look like George Raft or Edward G. Robinson, to smoke like the old movie stars used to smoke.

And here are these kids looking like they’re wearing their first decent suits, and who aren’t inhaling.

All gangsters were however presumably once young, including the four seminal figures in “Mobsters”: Lucky Luciano, Frank Costello, Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel. The movie traces their rise from the streets, in the years between the two world wars, and their gradual expansion from a small bootlegging business to virtual control of the mob. What made their four-way partnership special, in a criminal world dominated by Italians and Sicilians, was that two of them were Jewish, and all four had a greater loyalty to each other than to any of their other allies.

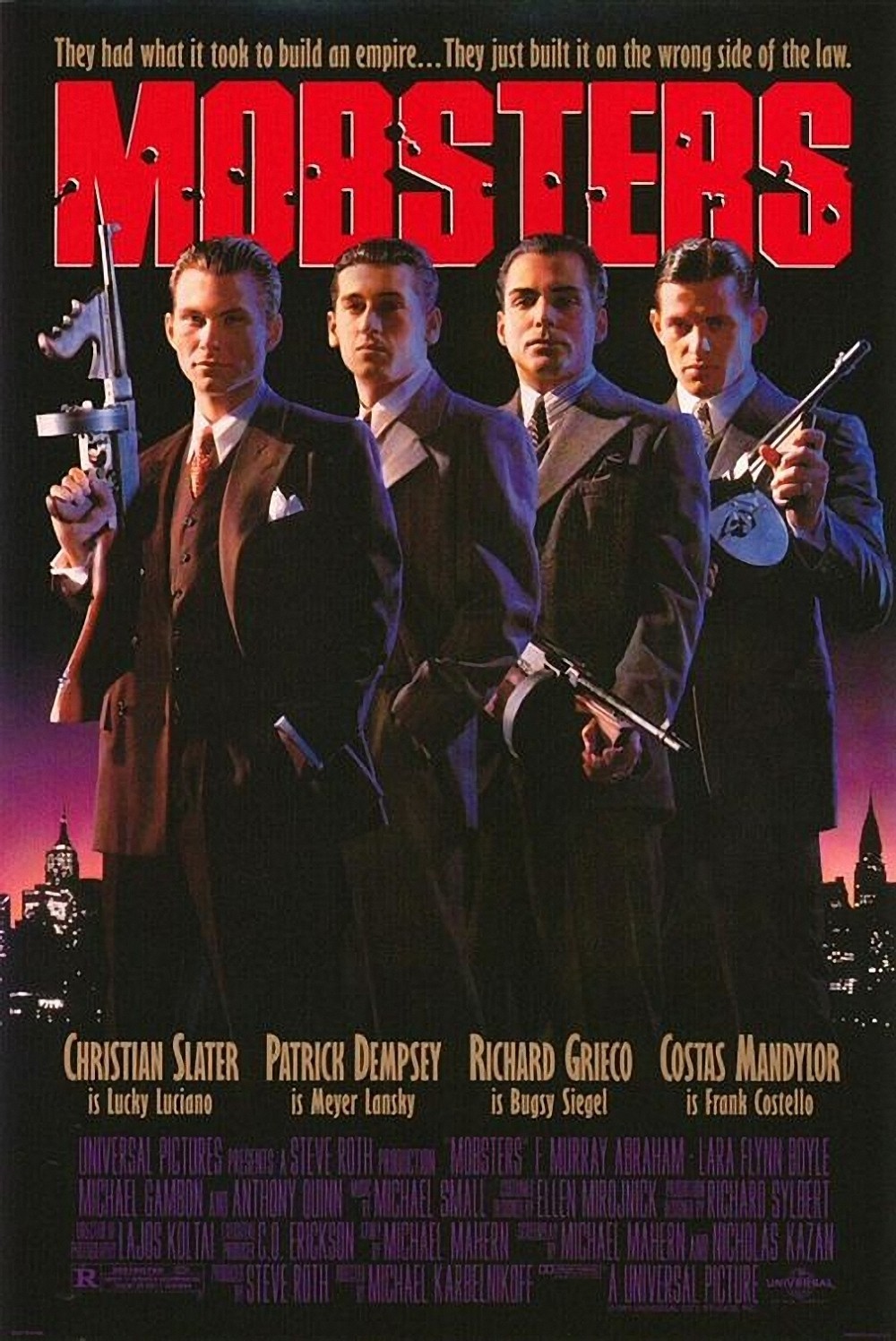

Their nominal leader was Luciano (Christian Slater), who is given that title after an interesting little scene with Lansky (Patrick Dempsey). Lansky has a guy tell a paperboy that a man in the back room has a job for him. The kid walks into the room, looks at Lansky and Luciano, and instinctively picks Luciano. He has the looks for the role. And Slater, who was impressive last year as a rebellious teenager in “Pump Up the Volume,” ages fairly convincingly here as a bad guy in his 20s or 30s.

The other two leading actors are Richard Grieco as Siegel and Costas Mandylor as Costello, and their mentors from the older generation include F. Murray Abraham as the gambler and fixer Arnold Rothstein, Anthony Quinn as a don named Masseria, and Michael Gambon, the thief in “The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover” as Masseria’s arch-enemy, Don Faranzano. Lara Flynn Boyle of “Twin Peaks” has one of the few female roles, as Lucky’s girlfriend.

It is a good cast and they are in a well-made movie, but I was never really convinced. I admired the way the movie looked, all drenched in browns, golds and reds (it uses the same palate as “The Godfather”), and I liked the convincing sets and the art design. I believed the actors most of the time, too, which is a small miracle considering that I’ve seen so many of them so recently playing completely different and much younger characters.

The problem is in the script, which is so complicated and violent that the credibility of the entire enterprise is undermined.

“Mobsters” is about the bloody rise of its four heroes to the top of the crime establishment, by means so devious and labyrinthine that you almost have to take notes to figure out who’s doing what, and why, and to whom. At one point, for example, having decided that the Quinn character must be killed, the four partners fake an attack on him, defend him, win his confidence by having saved his life, and then kill him. This is not the only double-reverse strategy in a movie which spends a good deal of the time with the characters explaining their strategy to each other, and to us.

The body count in the movie is fairly high, but that’s nothing compared to what’s done to the bodies before they’re counted.

This is the bloodiest gangster movie I can remember. Machineguns are emptied into dead bodies, a nose is bitten off, lips are cut off, a face is slowly and deliberately scarred, a man is dangled outside a hotel window before the rope is cut so he can fall to his death – and there are plenty of closeups of faces and bodies after such things have happened to them.

The violence and bloodshed are so far over the top, in fact, that they undermine the rest of the film, and approach parody.

“Mobsters” pretends to be a sociological study of the management levels of the mob, but it’s as bloodsoaked as any violent action picture (there’s more mayhem in it, for example, than in Jean-Claude Van Damme’s upcoming “Double Impact,” even though Van Damme is sold exclusively on his body counts).

What survives the gunfire and the screaming are some nice small moments in which the gangsters use intelligence to try to reason their way through the anarchy of the mob’s operational methods. Much is made of the fact that ethnic rivalries have been buried, that Jews and Italians are cooperating here for mutual benefit, that a character like Lansky always prefers to substitute negotiation for murder. When the movie slows down and takes a breath for these scenes, they work nicely and are well-acted. But too often the general noise level obscures the movie’s real achievements.