“MirrorMask” must have been a labor of love to make. Watching it is also a labor of love. The movie is a triumph of visual invention, but it gets mired in its artistry and finally becomes just a whole lot of great stuff to look at while the plot puts the heroine through a few basic moves over and over again.

The story involves Helena (Stephanie Leonidas), who is fed up with working for the Campbell Family Circus. “It’s your father’s dream,” says her mother Joanne (Gina McKee). Yes, but it’s not Helena’s dream, and she resents her parents for denying her an ordinary girlhood. “I hope you die,” she tells her mom, which is an unwise move for any character who even vaguely suspects she might be in a fantasy movie. Her mom promptly collapses and is hospitalized with an unspecified but alarming illness.

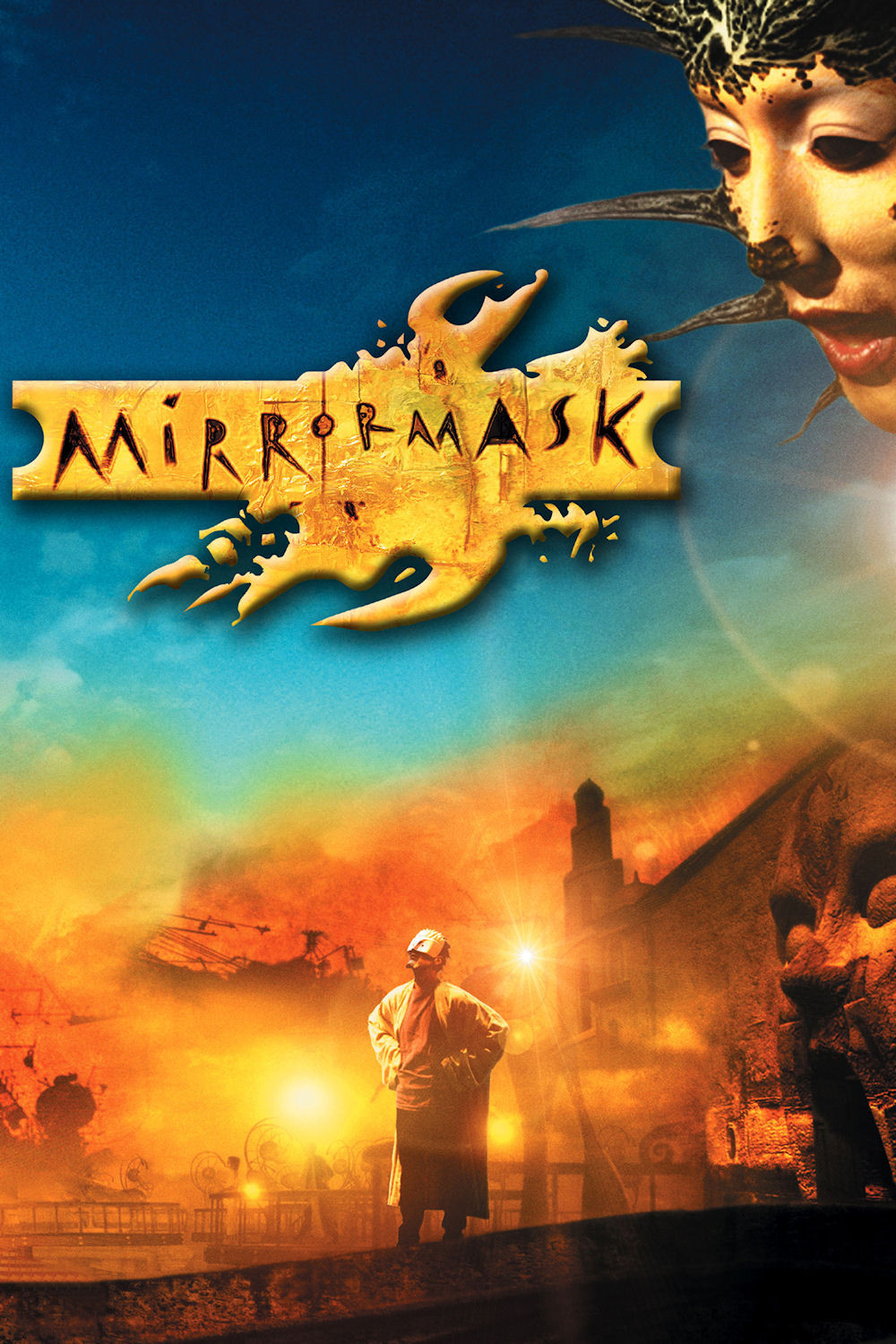

Helena’s fantasy life is lived through drawings of an imaginary city that looks as if Ralph Steadman were the mayor. Through a process best described by that reliable shortcut “magical,” she enters this world, a fantastical universe where fish swim through the air and the people from her real world appear transformed by bizarre masks and costumes. It is a world of light and dark; the Queen of Light (also played by Gina McKee) is in a trance-like state, and apparently it’s up to Helena to venture into the Dark World and return with the means to restore goodness and awaken the queen.

The movie’s fantasy world has an eerie beauty. This beauty enchanted me for several minutes, and then it began to wear on me, and finally it was a visual slog. Sorry. The story resembles what happens in Bernard Rose’s “Paperhouse” (1988), in which a girl draws a house in another world, falls ill, enters that world and finds herself responsible for saving the lonely little boy who lives in the house. In Rose’s film, the images are stark and clear, with the directness of a child’s drawings. In “MirrorMask,” with artist Dave McKean as director and production designer, the images are fuzzy and foggy and Helena encounters one weird scenario after another, in a world where the nonsense logic seems cloned from Wonderland.

Helena’s more hazardous adventures occur after she crosses over to the dark side, and is mistaken for her mirror image, a dark and sinister girl who apparently embodies all the sinister aspects of her subconscious. The Queen of Shadows (McKee again) mistakes Good Helena for Bad Helena, placing good Helena in some danger but also giving her access to information that may save the day — always assuming that Real Helena (who seems to have a separate existence) doesn’t bring everything to a sudden end by ripping her drawings from the walls.

Jason Barry has an important role as Valentine, a juggler who becomes Helena’s counselor in this alternative universe, and there are countless very strange creatures, some of them with shoes for heads, others weirder than that, who seem by Hieronymus Bosch out of an acid trip. One by one, frame by frame, these inventions are remarkable; stills from the film will give you an idea of the imagination that went into it.

But there’s no narrative engine to pull us past the visual scenery. Landscapes recede vaguely into dissolving grotesqueries as Helena wanders endlessly past one damn thing after another, and since everything that happens in this world is absolutely arbitrary, there’s no way to judge whether any action is helpful or not. It’s a world where no matter what Helena does, an unanticipated development will undo her effort and require her to do something else. Watching “MirrorMask,” I suspected the filmmakers began with a lot of ideas about how the movie should look, but without a clue about pacing, plotting or destination.