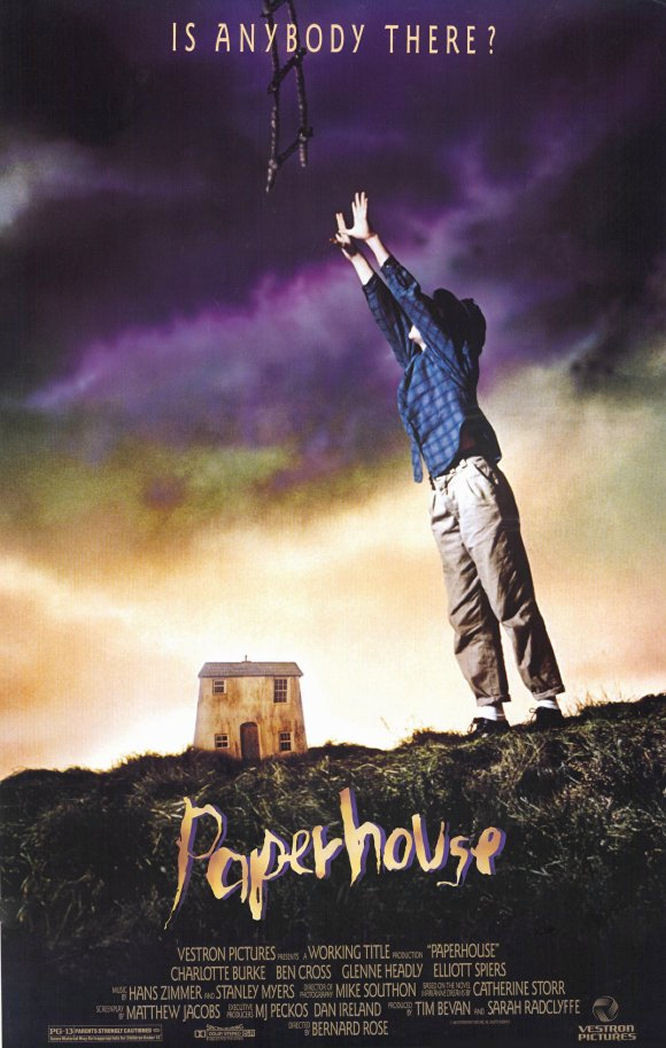

“Paperhouse” is a film in which every image has been distilled to the point of almost frightening simplicity. It’s like a Bergman film, in which the clarity is almost overwhelming, and we realize how muddled and cluttered most movies are. This one has the stark landscapes and the obsessively circling story lines of a dream – which is, of course, what it is.

The movie takes place during the illness of Anna (Charlotte Burke), a 13-year-old with a mysterious fever. One day in class, Anna draws a lonely house on a windswept cliff and puts a sad-faced little boy in the window. She is reprimanded by the teacher, runs away from the school, falls in a culvert and is knocked unconscious.

And then she dreams of a “real” landscape just like the one in her drawing, with the very same house, and with a sad boy’s face in an upper window. She asks him to come outside. He cannot, because his legs will not move, and because she has not drawn any stairs in the house.

Found by a search party, Anna is returned home, where her behavior is explained by the fever she has developed. The film alternates between Anna’s sickroom and her dream landscape, and very few other characters are allowed into her confined world. Among them, however, are her mother (Glenne Headly) and her doctor (Gemma Jones), and there are flashbacks to her absent father (Ben Cross), who is the distant and ambiguous father figure of so many frightening children’s stories.

The film develops a simple rhythm. Anna draws, dreams and then revises her drawings. She sketches in a staircase for the young boy, whose name is Marc, and fills his room with toys. She adds a fruit tree and flowers to the garden. And then one day she discovers, to her astonishment, that her doctor has another patient – a boy named Marc, who faces paralysis, and about whom she is very concerned.

“Paperhouse” wisely never attempts to provide a rational explanation for its story, although we might care to guess that the doctor is sort of a psychic conduit allowing Anna and Marc to enter each other’s dreams. Anna rebels briefly against the notion that she is someone playing God for Marc, but then accepts the responsibility of her drawings and her dreams.

“Paperhouse” is not in any sense simply a children’s movie, even though its subject may seem to point it in that direction. It is a thoughtfully written, meticulously directed fantasy in which the actors play their roles with great seriousness. Watching it, I was engrossed in the development of the story and found myself accepting the film’s logic on its own terms.

The movie’s director is Bernard Rose, a young Briton who had some success with music videos before this first feature. He carries some of the same visual inventiveness of the best music videos over into his images here, paring them down until only the essential elements are present, making them so spare that, like the figure of Death in Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal,” they seem too concrete to be fantasies.

I will not discuss the end of the movie, except to say that it surprised and pleased me. I don’t know what I expected – some kind of conventional plot resolution, I suppose – but “Paperhouse” ends instead with a bittersweet surprise that is unexpected and almost spiritual.

This is not a movie to be measured and weighed and plumbed, but to be surrendered to.