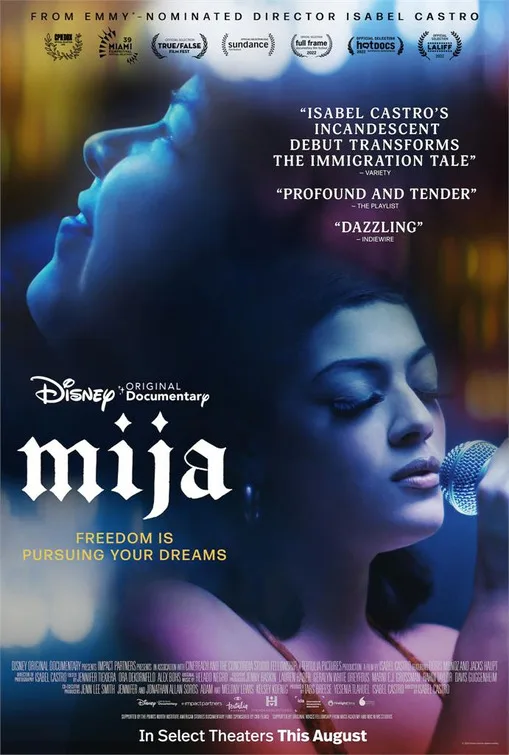

For Doris Muñoz, the burden of dreams is a heavy one. The American-born daughter of undocumented Mexican immigrants, she talks about the “pressure to honor” her parents’ “sacrifices,” noting that “it takes a lot of courage to make your own path.” That statement could apply equally to Doris herself, a fledgling manager dedicated to discovering and promoting Latinx alternative music. Two generations of Muñozes have marched into the unknown in pursuit of a dream, and the sorrows and rewards of their journey are the subject of the biographical documentary “Mija.”

“Mija” was directed by Isabel Castro, a Mexican-American documentarian who makes the leap from TV to features with this Sundance Labs project. She does so with a sense of profound empathy with her subjects, all of whom come from similar—but not identical—backgrounds. As a result, “Mija” weaves a more nuanced emotional tapestry than is typically seen in immigration stories like this one. Yes, sadness and fear are present. But gratitude, resentment, guilt, stress, hope, and excitement are also essential to Doris’ story, her family’s story, and the Mexican-American community at large.

All of these emotions are expressed through music, which forms the backbone of the film. Ecuadorian-American avant-pop artist Helado Negro wrote the score for the film, and the soundtrack is stuffed with tracks from Latinx indie acts like Divino Niño, Omar Apollo, Buscabulla, KAINA, and The Marias. These supplement the two artists who actually appear as themselves in “Mija”: Cuco, the bedroom-pop sensation Doris is managing at the beginning of the film, and Jacks Haupt, a Chicana teenager from Dallas obsessed with Amy Winehouse and Lana Del Rey who Doris scouts on Instagram.

The performance scenes that dot the film sway under dreamy multicolored lights, highlighting the escapist qualities of the music while using the relative sizes of venues and crowds to show where Cuco and Jacks are in their careers. Behind-the-scenes glimpses of recording sessions and photo shoots are more varied: Some are downright romantic, while others show the more monotonous side of the business. Jacks’ parents don’t approve of their daughter’s risky career moves, and chew her out on speakerphone more than once during her big career-making trip to L.A. Through it all, Doris stands in the background, feeling responsible for everyone and everything.

That sense of obligation carries through to her relationship with her family. They depend on Doris to serve as a liaison between her brother—who was deported a few years back and now lives in Tijuana—and the rest of the family, who can’t cross the border to visit him. Doris is also sponsoring her parents’ green cards, and takes on these duties without complaint. She loves her family, and is grateful for everything her parents have done for her. But she does feel lonely, especially when her career isn’t going well. “I just spread myself so thin,” she tells the camera. “Saying yes to everyone, trying to take care of everyone, and then … it feels like I’m letting down anyone who ever believed in me.”

The film opens with a scene of Doris shopping at a colorful Mexican party-supplies store that’s a riot of colors and textures. And Castro’s impressionistic style does keep the film interesting on a visual level as well as an emotional one. Her point of view is extremely strong, expressing the laid-back attitude of many of her subjects—at one point, Doris’ brother tells her she needs to “go with the flow” more often—in the editing of the film. Together, the film’s vivid details and relaxed rhythm form a sense of a specific time, place, and culture, a world where forgetting the lyrics to a Selena song on stage is all that it takes to sink an artist’s career.

First-person narration written by Muñoz, as well as the frequent breaking of the fourth wall, give “Mija” an intimacy that expresses itself as love. Scenes where Doris and Jacks bond over their shared fears and ambitions feel real and heartfelt, as does a real wallop of a tearjerker ending. Unfortunately, however, that isn’t always true for the connective tissue linking these profound moments: Several expository scenes were clearly set up in order to get the sound bites that Castro needed to link disparate clips together.

An extended pause in shooting during COVID-19 lockdowns also hobbles “Mija,” but to a lesser extent. In a way, it actually benefits the doc, as it gives Doris time to regroup after a professional setback and introduces an element of physical separation to a story that was already exploring borders and barriers. The bigger issue is Castro’s struggle to clearly differentiate between Jacks’ and Doris’ storylines when “Mija” branches out midway through. The film does regain its focus towards the end, but not without some lost momentum. None of these narrative weaknesses dull this enchanting film’s emotional impact, however—or its hard-won sense of optimism.

Now playing in select theaters and available on Disney+ on September 16.