This review contains spoilers. Oh, yes, it does, because I can’t imagine a way to review “Midnight in Paris” without discussing the delightful fantasy at the heart of Woody Allen‘s new comedy. The trailers don’t give it away, but now the reviews from Cannes have appeared, and the cat is pretty much out of the bag. If you’re still reading, give yourself a fair chance to guess the secret by reading through the list of character names in the credits: “Gert.” Which resident of Paris does that make you think of?

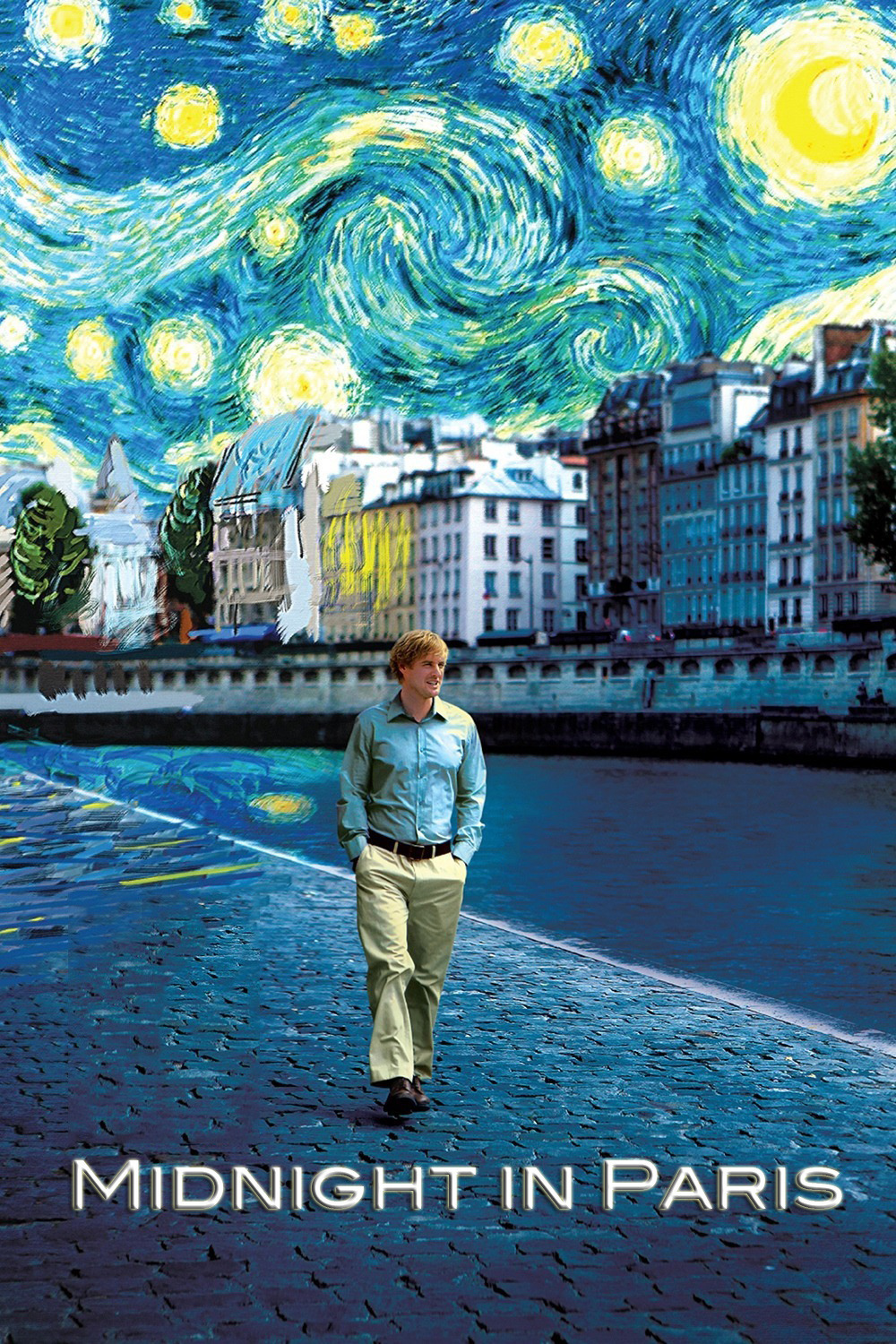

This film is sort of a daydream for American lit majors. It opens with a couple on holiday in Paris with her parents. Gil (Owen Wilson) and Inez (Rachel McAdams) are officially in love, but maybe what Gil really loves is Paris in the springtime. He’s a hack screenwriter from Hollywood who still harbors the dream of someday writing a good novel and joining the pantheon of American writers whose ghosts seem to linger in the very air he breathes: Fitzgerald, Hemingway and the other legends of Paris in the 1920s.

He’d like to live in Paris. Inez would like to live in an upper-class American suburb, like her parents. He evokes poetic associations with every cafe where Hemingway might once have had a Pernod, and she likes to go shopping. One night, he wanders off by himself, gets lost, sits on some church steps, and as a bell rings midnight, a big old Peugeot pulls up filled with revelers.

They invite him to join their party. They include Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Allen makes no attempt to explain this magic. None is needed. Nor do we have to decide if what happens is real or imaginary. It doesn’t matter. Gil is swept along in their wake and finds himself plunged into the Jazz Age and all its legends. His novel was going to be about a man who ran a nostalgia shop, and here he is in the time and place he’s most nostalgic for.

Some audience members might be especially charmed by “Midnight in Paris.” They would be those familiar with Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, and the artists who frequented Stein’s famous salon: Picasso, Dali, Cole Porter, Man Ray, Luis Bunuel and, yes, “Tom Eliot.” Allen assumes some familiarity with their generation, and some moviegoers will be mystified, because cultural literacy is not often required at the movies anymore. Others will be as charmed as I was. Zelda is playfully daffy, Scott is in love with her and doomed by his love, and Hemingway speaks always in formal sentences of great masculine portent.

Woody Allen must have had a great time writing this screenplay. Gil is of course the Woody character (there’s almost always one in an Allen film), and his fantasy is an enchanted wish-fulfillment. My favorite of all the movie’s time-lapse conversations may be the one Gil has with Bunuel. He gives him an idea for a film: A group of guests sit down to dinner and after the meal is over, they mysteriously find themselves unable to leave the house. “But why not?” Bunuel asks. “They just can’t,” Gil explains. Bunuel says it doesn’t make any sense to him. If the story idea and perhaps the name Bunuel don’t ring a bell, that’s a scene that won’t connect with you, but Allen seems aware that he’s flirting with inside baseball, and tries to make the movie charming even for someone who was texting all during high school.

Owen Wilson is a key to the movie’s appeal. He makes Gil so sincere, so enthusiastic, about his hero worship of the giants of the 1920s. He can’t believe he’s meeting these people, and they are so nice to him — although at the time, of course, they didn’t yet think of themselves as legends; they ran into ambitious young writers like Gil night after night in Miss Stein’s salon.

Another treasure in the film is Kathy Bates’ performance. She is much as I would imagine Gertrude Stein: an American, practical, no-nonsense, possessed with a nose for talent, kind, patient. She’s something like the Stein evoked by Hemingway in A Moveable Feast, his memoir of this period. She embodies the authority that made her an icon.

Then there’s Adriana (Marion Cotillard), who has already been the mistress of Braque and Modigliani, and is now Picasso’s lover, and may soon — be still, my heart! — fall in love with Gil. Compared to her previous lovers, he embodies a winsome humility, as well he might. Meanwhile, life in the present continues, with Gil’s bride-to-be and future in-laws increasingly annoyed by his disappearances every night. And there’s another story involving a journey even further into the past, indicating that nostalgia can change its ingredients at a movable feast.

This is Woody Allen’s 41st film. He writes his films himself, and directs them with wit and grace. I consider him a treasure of the cinema. Some people take him for granted, although “Midnight in Paris” reportedly charmed even the jaded veterans of the Cannes press screenings. There is nothing to dislike about it. Either you connect with it or not. I’m wearying of movies that are for “everybody” — which means, nobody in particular. “Midnight in Paris” is for me, in particular, and that’s just fine with moi.