There are times in “Mephisto” when the hero tries to explain himself by saying that he’s only an actor, and he has that almost right: All he is, is an actor. It’s not his fault that the Nazis have come to power, and that as a German-speaking actor he must choose between becoming a Nazi and being exiled into a foreign land without jobs or German actors. As long as he is acting, as long as he is not called upon to risk his real feelings, this man can act his way into the hearts of women, audiences, and the Nazi power structure. This is the story of a man who plays his life wearing masks, fearing that if the last mask is removed, he will have no face.

The actor is played by Klaus Maria Brandauer in one of the greatest movie performances I’ve ever seen. The character is not sympathetic, and yet we identify with him because he shares so many of our own weaknesses and fears. He is not a very good actor or a very good human being, but he is good enough to get by in ordinary times. As the movie opens, he’s a socialist, interested in all the most progressive new causes, and is even the proud lover of a black woman. By the end of the film, he has learned that his politics were a taste, not a conviction, and that he will do anything, flatter anybody, make any compromise.

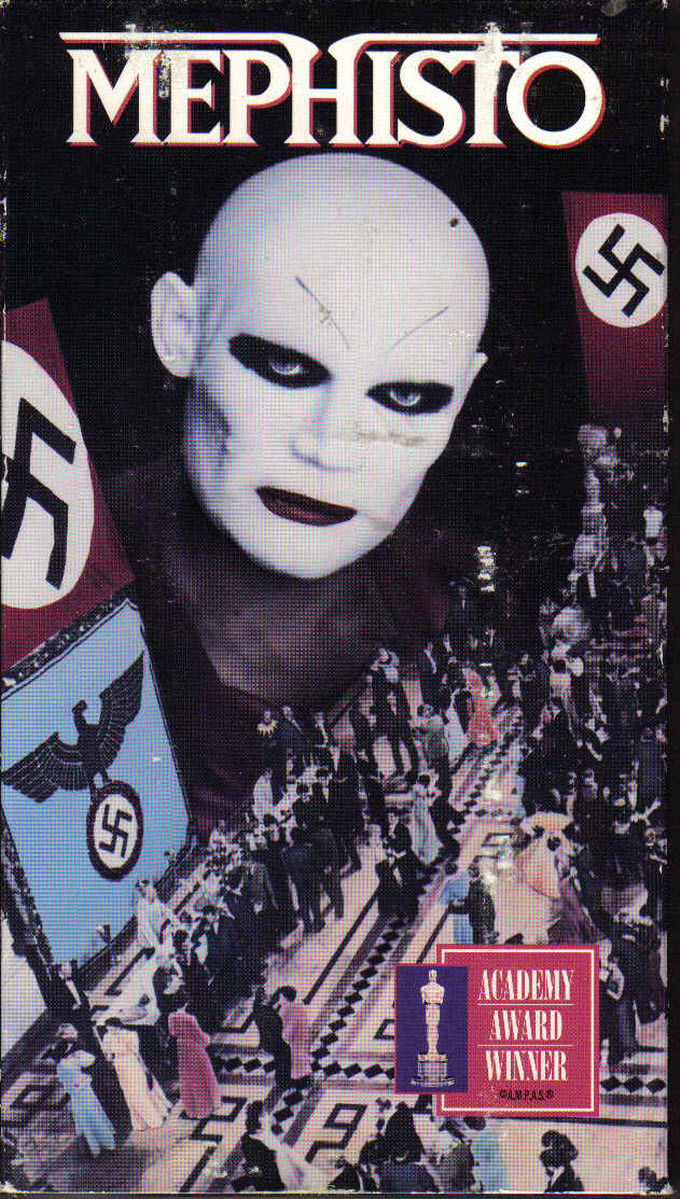

“Mephisto” does an uncanny job of creating its period, of showing us Hamburg and Berlin from the 1920s to the 1940s. I’ve never seen a movie that does a better job of showing the seductive Nazi practice of providing party members with theatrical costumes, titles and pageantry. In this movie not being a Nazi is like being at a black-tie ball in a brown corduroy suit. Hendrik Hoefgen, the actor, is drawn to this world like a magnet. From his ambitious beginnings in the provincial German theater, he works his way up into more important roles and laterally into more important society.

All of his progress is based on lies. He marries a woman he does not love, because her father can do him some good. When the rise of the Nazis destroys his father-in-law’s power, he leaves his wife. He continues all this time to maintain his affair with his black mistress. He has a modest but undeniable talent as an actor, but prostitutes it by playing his favorite role, Mephistopheles in “Faust,” not as he could but as he calculates he should.

The obvious parallel here is between the hero of this film and the figure of tragedy who sold his soul to the devil. But “Mephisto” doesn’t depend upon easy parallels to make its point. This is a human story, and as the actor in this movie makes his way to the top of the Nazi propaganda structure and the bottom of his own soul, the movie is both merciless and understanding. This is a weak and shameful man, the film seems to say, but then it cautions us against throwing the first stone.

“Mephisto” is not a German but a Hungarian movie, directed by Istvan Szabo, the talented 44-year-old who has led his country’s cinema from relative obscurity to its present position as one of the best and most innovative film industries in Europe. Szabo, in his way, has made a companion film to Fassbinder’s “The Marriage of Maria Braun.” The Szabo film shows a man compromising his way to the top by lying to himself and everybody else, and throwing aside all moral standards. It ends as World War II is under way. The Fassbinder film begins after the destruction of the war, showing a woman clawing her way out of the rubble and repeating the same process of compromise, lies, and unquestioning materialism.

Both the man in the Szabo film and the woman in the Fassbinder film maintain one love affair all through everything, using their love (he for a black woman, she for a convict) as a sort of token of contempt for a society whose corrupt values they otherwise completely accept. The fact that they can still love, of course, makes it impossible for them to quite deceive themselves. That is the price they pay for their deals with the devil.