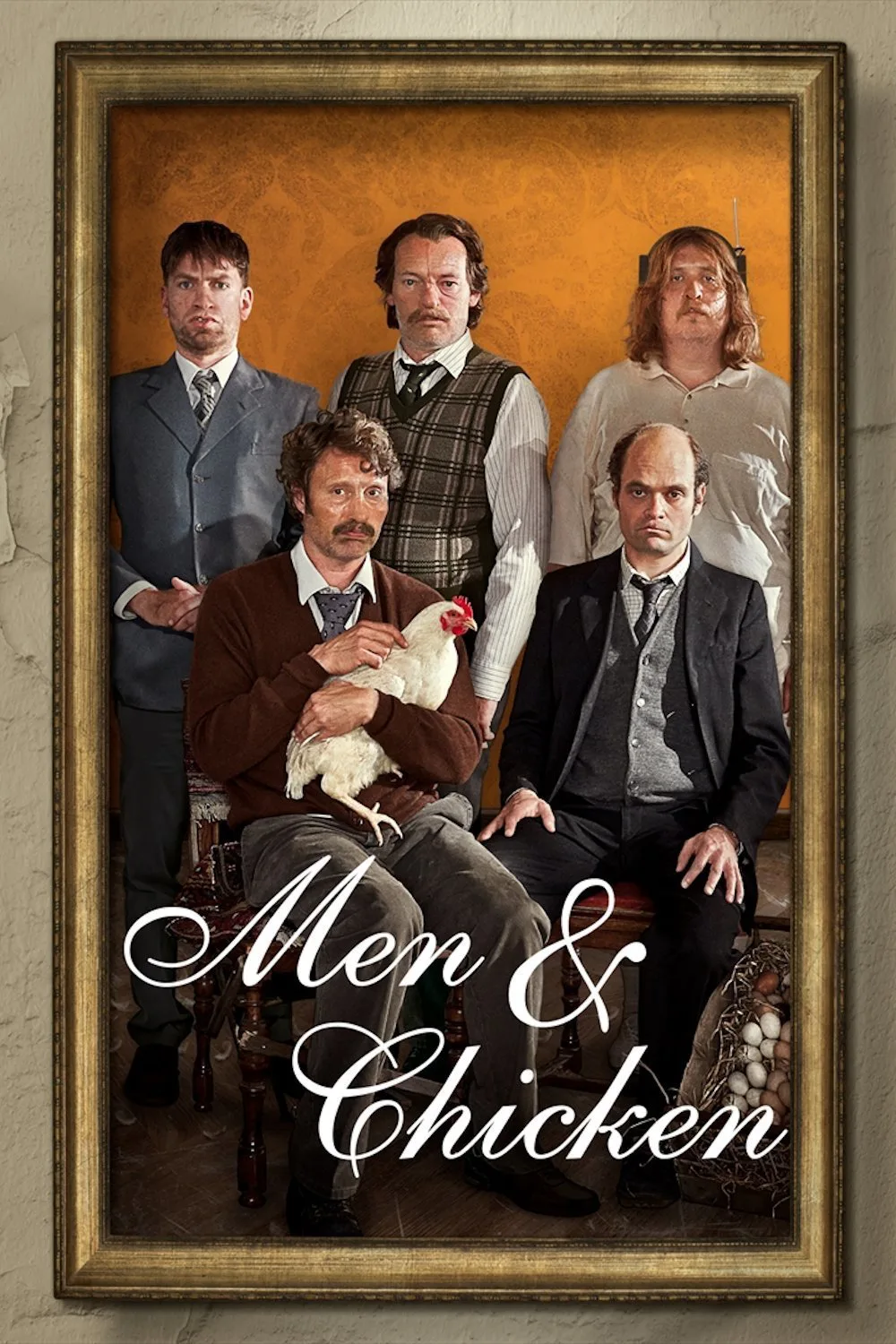

David Dencik and Mads Mikkelsen play estranged brothers Gabriel and Elias, respectively, in writer/director Anders Thomas Jensen’s bizarre “Men & Chicken.” The two men are thrown together when, after their father’s death, some family secrets come to light. The comedy in “Men & Chicken” sometimes tips into Keystone Cops territory, with people running around in the background like chickens (of course) with their heads cut off. “Men & Chicken” is a bizarre family psychodrama as well as a mad-scientist movie, complete with a crazy spooky lab full of terrifying objects. How seriously should any of it be taken? It’s hard to tell, but the film has a dry eccentricity that is entertaining and absurd. You don’t know what will happen next. If the hundreds of chickens clucking around in the movie revealed themselves as sentient beings with the power of speech it wouldn’t be a surprise at all. In the world of “Men & Chicken,” all manner of ridiculous things seem possible.

Gabriel and Elias set off together on a road trip to the isolated Ork Island (population 42) to seek out the brothers they never knew they had. Both have cleft palates as well as personality quirks (putting it mildly), and they can barely get through a conversation without running into intractable conflict. They have circular arguments about Darwin and Einstein. (“Einstein won the Nobel Prize, Elias.” “Yes. In 1921, the lamest year in physics.”) Elias is first seen on a date with a woman in a wheelchair who makes the fatal error of accidentally interrupting him. He snaps, “Do all people in wheelchairs interrupt this much?” Not surprisingly, Elias has no luck with women, particularly unfortunate for him since his sex drive is so titanic that he needs to masturbate multiple times a day. Elias’ “condition” is treated matter-of-factly by his brother (who pulls over to the side of the road to let Elias get out and do his thing behind a tree). Gabriel is a philosophy professor who dry-retches and gags every other minute for unknown reasons.

Elias and Gabriel track down their three half-brothers holed up in a dilapidated former sanitarium, overrun by chickens, ducks, goats. The brothers call to mind the locals in “Deliverance“: They are barely civilized, beating one another (and Gabriel when he first approaches) with huge dead birds or slabs of wood. They threaten each other with “the cage” for rule infractions. It’s a madhouse. They all have cleft palates and other physical abnormalities and live in a raw state of nature (putting the lie to Rousseau’s theories). They are petty, vicious, savage, rule-bound. Interrupting one another is strictly forbidden.

The sanitarium is an incredible and inherently cinematic location, utilized beautifully by Jensen. There are echoing long hallways, mysterious upstairs rooms and an off-limits basement. There is no electricity. The brothers play badminton in one room, all wearing tennis whites, and they treat the game as seriously as a World Cup match. At any time, a fist fight could break out. Every night they curl up by the fire and have a bedtime story hour, where they discuss plot points and character analysis, and nobody is allowed to interrupt anyone else, and of course nobody can obey that rule perfectly. The family unit is a tinderbox. The ensemble acting is terrific.

Gabriel, determined to find answers about their shared background, tries to wrestle the wild brothers under control. Elias, however, takes to the chaos like a duck to water. Within 24 hours, he’s dressed up in tennis whites playing badminton as though he had lived there all his life. He never wants to leave.

Mads Mikkelsen, an exquisite actor, so elegant, controlled and frightening as Hannibal on NBC’s “Hannibal,” is barely recognizable as the constant-masturbator Elias. He’s got a haircut and a mustache reminiscent of Christopher Walken’s sleazy look in “At Close Range.” But it’s not just the externals that make him unrecognizable. Elias is chatty, impulsive, rude, irritated by his frustrated sex drive. Mikkelsen, as Elias, is always thinking, processing, eyes shifting around as he takes in new information. He thinks so much more than he says, and that’s one of the reasons that the performance is so funny. It’s not strange just for the sake of being “wacky” or “quirky.” Mikkelsen has made sense of Elias, and has connected all of those disparate pieces to create a very real character. Humphrey Bogart once said that good acting was six feet back in the eyes. Mikkelsen goes that deep, and that’s why he is so transformed. Elias is so strange that one might struggle to place him, or compare him to someone else. But he is his own thing, and you can’t take your eyes off of him.

Strange motifs and themes emerge and recur: copious ejaculation, dead birds, evolutionary mutations, hybrid breeds, survival of the fittest, inherited characteristics. Nature creates “monsters,” and man can create monsters of his own. Jensen uses horror movie tropes: strange things glimpsed at night, closed doors, phonographs playing in empty rooms. But there are farcical elements too: the brothers running around the sanitarium wielding badminton rackets, the repeated beatings with a stiff dead bird and the casual discussions afterwards (“I’m not mad at you for beating Gabriel with the mute swan. It happens to the best of us.”) There’s also a grotesque element, in the traditional sense of the word: “freaks,” cages, mutations limping through their lives. What was their father up to? What’s with the cleft palates? What is in that basement? At some point, is someone going to sexually assault a chicken? It is discussed as a valid option.

Audience members looking for a character to “relate to” or “like” may have a rough time. But nobody is likable in farce or absurdist black comedy: it’s not that kind of genre, nor should it be. What does all of this add up to? Damned if I know. But it’s fun to see a film that plays by its own rules to such a degree that any comparison to anything else falls apart.