“Medicine for Melancholy” is nothing more or less than the story of a man and a woman spending 24 hours together. It has no other agenda, which is part of its charm. Haven’t we all spent some interesting time together with a stranger, talking a little about our lives, sharing a certain communion, with no certainty that we will ever see them again?

Micah and Joanne are African-Americans in their late-20s, who wake up next to each other in a bed in an expensive home on San Francisco’s Nob Hill. They are hung over. They don’t know each other’s names. She wants to go home and forget. He persuades her to have breakfast. In a perhaps symbolic walk across a hill into a less posh neighborhood, he tries to cheer her up. It becomes clear that in a city with a 7% black population, he sees her as intriguing: A single, hip black woman in what he describes as the “indie world.”

They talk. They take a taxi to her neighborhood–not to her door. She left her wallet in the cab. He discovers she is Joanne, not “Angela.” He tracks her down on his bike. He kids her. They bike to an art gallery. Then they go through a couple of museums. They’re getting to like one another.

Micah is interested in stereotypes. He observes that two black people spending Sunday at art museums does not fit the stereotype. Whose? His, I think. She asks what race has to do with it. He says his identity, in the eyes of the world, is as a black man. “That’s what people see.” Who would speculate he supplies and maintains upscale private aquariums? And Joanne? Her expensive condo in the Marina belongs to her lover, a white man now in London on business. He is an art curator, although Micah observes there is not a single art work in the condo.

“Does it matter that he’s white?” she asks. “Yes and no,” Micah says. A good answer. The day does not continue their discussion of interracial dating. It becomes more of a test-drive of a possible life together. Neither seriously expects to lead such a life, but it’s intriguing to play. At one point they go to Whole Foods. When a newly- met couple go grocery shopping together, they’re playing house.

Micah is concerned with demographics and residential patterns. He passionately loves San Francisco, and has seen gentrification push out the populations and neighborhoods that gave it flavor. All men need a lecture topic when trying to impress a woman, and this is his. At one point the film drops in on a completely unrelated discussion group about housing policy; it’s the sort of detour you might find in “Waking Life.”

The actors are effortlessly engaging. Tracey Heggins plays skittish at first, then warmer and playful. Is she having a better time than she usually has with her white lover? Yes. Well, maybe yes and no. She doesn’t talk enough about him for us to be sure. Wyatt Cenac plays a smart charmer; the urban facts he cites are a reminder of his comedy alter ego, the “Senior Black Correspondent” on Jon Stewart’s Daily Show.

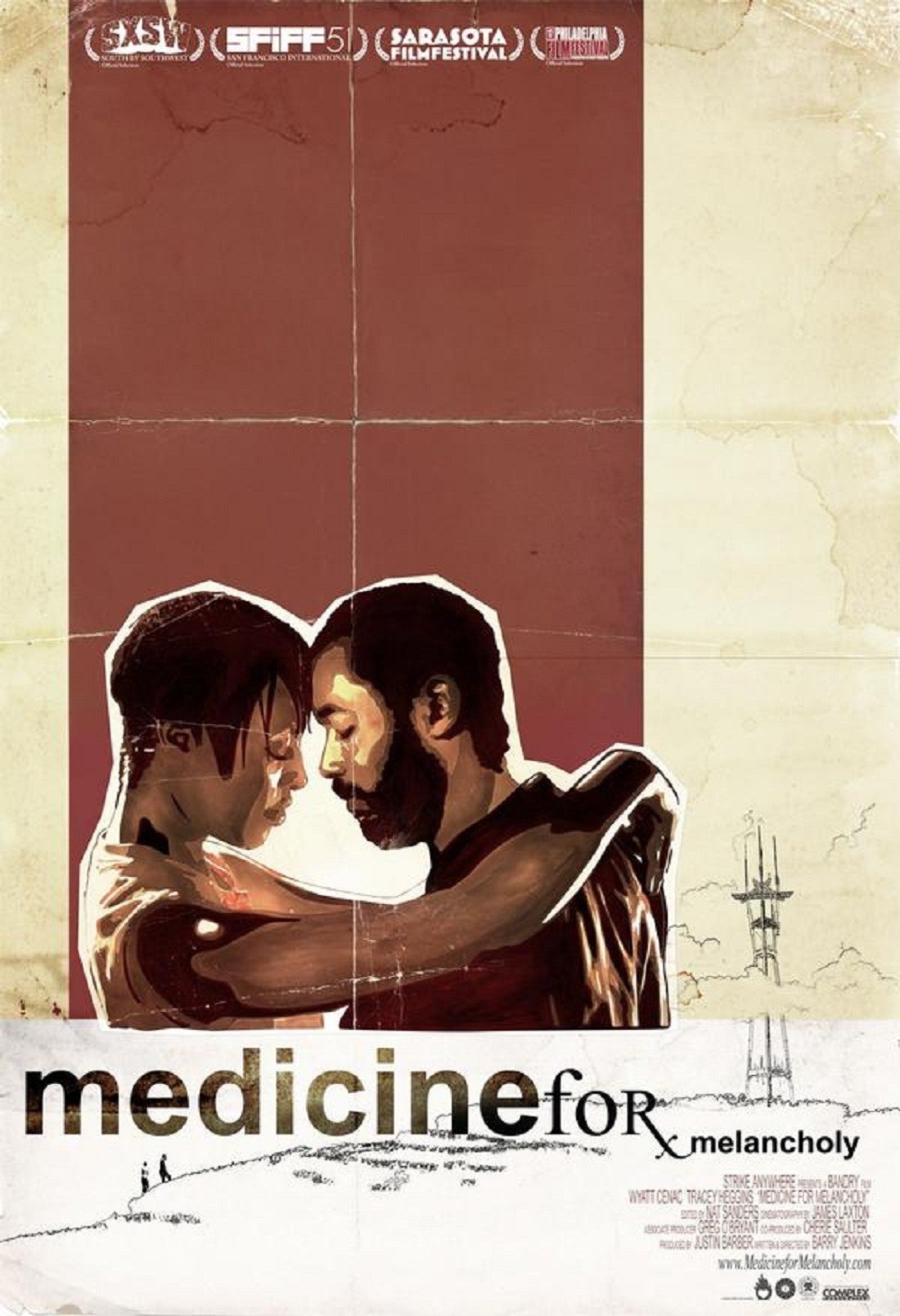

“Medicine for Melancholy” is a first, but very assured, feature by Barry Jenkins, who has the confidence to know the precise note he wants to strike. This isn’t a Statement film or a bold experiment in style; it’s more like a New Yorker story that leaves you thinking, yes, I see how they feel. The film is beautifully photographed by James Laxton; much of the color is drained, making it almost b&w. The critic Karina Longworth writes: “I guessed that the entirety of the film had been desaturated 93 percent to match the racial breakdown, but in a recent interview, Jenkins said the level of desaturation actually fluctuates.” The visual effect is right; McLuhan would call this a cool film.

* * *

Unlike most small indie films, this is one that you, yes you, North American reading this review, can actually see. Many readers complain that “art films” never play in their town, or even their state.

“Medicine for Melancholy” is part of a “Festival Direct” collaboration between IFC and Austin’s important South by Southwest Festival in Austin, which will make SXSW films available via on-demand on many cable systems, including Comcast, Charter, Cox, Time Warner, and Cablevision.

This movie is discussed in a blog entry, here: http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/2009/03/dont_move_i_want_to_move_dont.html