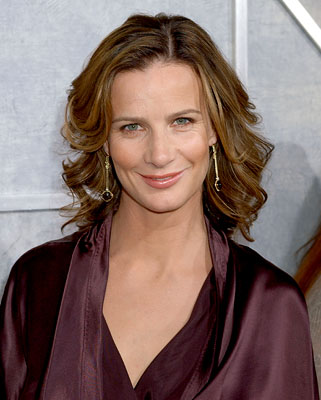

Consider now Rachel Griffiths. I first noticed her as the best friend with the infectious grin in “Muriel's Wedding,” the quirky Australian comedy. She was the lusty pig-farmer’s daughter who briefly married the earnest student in “Jude.” In “Hilary and Jackie,” she played the sister of the doomed musician and won an Oscar nomination.

She was wonderful in two films that didn’t find wide distribution: “My Son, the Fanatic,” where she played a hooker who forms a sincere friendship with a middle-aged Pakistani taxi driver in the British Midlands, and “Among Giants,” where she was a backpacking rock climber who signs up for the summer with a crew of British power pylon painters. That was the movie where, on a bet, she traversed all four walls of a pub with her toes on the wainscoting, finding finger holds where she could.

It is quite possible that Griffiths made all of these movies without coming to your attention, since none of them were big box-office winners and a depressing number of moviegoers march off like sheep to the weekend’s top-grossing hot-air balloon. She’s been in one hit, “My Best Friend's Wedding,” but not so you’d notice.

I think she is one of the most intensely interesting actresses at work today, and in “Me Myself I” she does something that is almost impossible: She communicates her feelings to us through reaction shots while keeping them a secret from the other characters. That makes us conspirators.

Griffiths is not a surface beauty but a sexy tomboy with classically formed features, whose appeal shines out through the intelligence in her eyes and her wry mouth. You cannot imagine her as a passive object of affection. If Hollywood romances were about who women were, rather than how they looked, she’d be one of the most desirable women in the movies. To the discerning, she is anyway.

“Me Myself I” is a fantasy as contrived and satisfactory as a soap opera. Griffiths plays Pamela, a professional magazine writer in her 30s who smokes too much and keeps up her spirits with self-help mantras (“I deserve the best and I accept the best”).

Her idea of a date is to open a bottle of wine and look at photos of guys she dated 15 years ago. “Why did I let you go?” she asks the photo of Robert (David Roberts). She’s attracted to a crisis counselor named Ben (Sandy Winton), but finds out he is happily married, with children.

Should she have married Robert all those years ago? An unexplained supernatural transfer takes place, and she gets a chance to find out. She’s hit by a car, and the other driver is–herself. After a switch, she finds herself living in an alternate universe in which she did marry Robert and they have three children. This of course is all perfectly consistent with the latest theories in quantum physics; only the mechanism of the transfer remains cloudy.

Here is the key to the transformation scenes: Pamela knows she is a replacement for the “real” Pamela in this parallel world, and so do we, but everyone else fails to notice the substitution (except for Rupert, the youngest, who asks her bluntly, “When’s Mommy gonna be home?”).

There are scenes involving cooking dinner, managing the house, and co-piloting for Rupert during his toilet duties. And a sex life with Robert that he finds surprising and delightful, since he and his original Pamela had cooled off considerably.

In this parallel universe, Ben is single, not married, and she takes the chance to have an affair with him, despite the complication now she is married, not single.

When she thinks Robert has been unfaithful, she is outraged, as much on behalf of the other Pamela as for herself, although in the new geometries of the universe-switch they are equally guilty, or innocent.

This new Robert also has to be trained to accept an independent woman. When she announces that she needs a new computer and he says, “We’ll see,” she jolts him with: “I’m not asking your permission.” There are sweet scenes in the film and touching ones. My favorite moments come when Pamela does subtle double-takes when she realizes how her life is different now and why. The plot is not remarkably intelligent, but Pamela (or Griffiths) is, and her reaction shots, her conspiratorial sharing of her thoughts with us, is where the movie has its life.

Griffiths’ career is humming right along, if the criteria are that she stars in good roles in interesting movies, and is able to use her gifts and her intriguing personality. It could stand some improvement if the criteria are that she appears in big hits and makes $20 million a picture.

The odds are she is too unique to ever make that much money; she isn’t generic enough. And remember that the weekend box-office derby is usually won by the movie appealing to teenage boys. She doesn’t play the kinds of women who are visible to them yet.

All of this is beside the point for evolved moviegoers such as ourselves, who know a star when we see one.