Thomas Hardy’s bleak and shocking novel “Jude the Obscure,” published in 1895, told the story of a stonemason who dreamed of becoming a scholar, but was crushed by the British social system, by fate and by his own rotten luck. The novel created such an uproar when it was published that Hardy never wrote another one, retreating into his poetry and an old age of rural seclusion.

Now it has been filmed as “Jude,” an angry saga that just barely manages to find a bittersweet ending by overlooking the novel’s final pages–which are even grimmer, if you can believe it, than the sad events we see on the screen. Only the energy of the leading actors and the glory of the photography rescue the film from the slough of despond–and in a way, Hardy might have thought, that’s cheating. The novel argues that with society and conventional morality arrayed against you, there’s not much you can do.

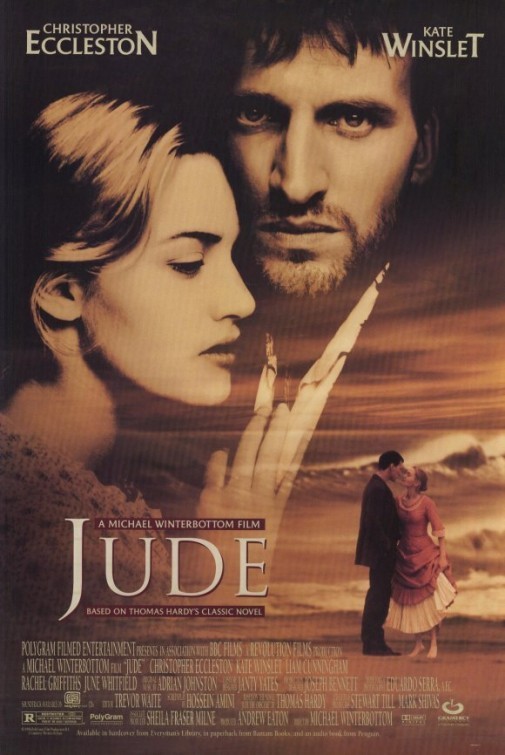

The movie stars Christopher Eccleston as Jude Fawley, a stonemason from a small village whose tutor, Phillotson, takes him to the top of a hill and shows him the towers of Christminster (which is meant to be Oxford). “If you want to do anything in your life, Jude,” he tells him, “that’s where you have to go.” But the boy has few opportunities and no money, and soon he is courting Arabella (Rachel Griffiths), a pig farmer’s daughter. They make love in a barn, their passion accompanied by the noises of the animals. She thinks she is pregnant, they marry, and their marriage is symbolized in a scene where Arabella dresses a pig carcass while he studies Greek and Latin.

Arabella, played by Griffiths as a sturdy, lusty woman with plans of her own, abandons Jude when she comes to believe that she is not pregnant and leaves for Australia. Jude goes to Christminster, where he falls in love at first sight with his cousin, Sue (Kate Winslet, from “Sense and Sensibility”) and follows her to a socialist meeting. He studies for his entrance exams, and takes her to meet Phillotson (Liam Cunningham), who offers her a teaching job.

Jude’s hopes of gaining admission to Christminster are dashed by the class system; not many self-taught manual laborers were accepted into British universities at the time, and there is a poignant scene where Jude, rejected as a scholar, defiantly recites the Creed in Latin in a pub, to an audience of drunken proles who mock his learning.

Sue wants to marry Jude, but when he reveals he’s already married, she marries Phillotson on the rebound. The marriage doesn’t work, and Phillotson himself observes, “I think you are one person split in two.” Soon they are living together in sin, and Sue’s refusal to even pretend to be married causes them to become outcasts; Jude loses a job at a church, they are thrown out of lodgings, and eventually they’re reduced to selling pastries at street fairs.

In the meantime, Jude has adopted a son by Arabella (who was pregnant after all) and had two more by Sue–allowing his solemn-faced boy to watch during one childbirth. The couple sink into poverty and despair, moving from one bolt-hole to another, while the older son looks on with quiet despair.

The film’s tone is set in the opening black-and-white sequence, where Eduardo Serra’s photography places small figures on a horizon and composes the shot so that a vast, dark, wet field of mud and rocks looms up to a sliver of sky. He and the director, Michael Winterbottom, create a convincing period landscape and townscape for “Wessex,” the fictional county where Hardy’s novels are set: Shops and cottages, streets and markets look beautiful as compositions, but the film gradually reveals its world as one with no comfort for the outcasts of this story.

What was Hardy arguing in his novel? Many of his books were about ordinary working-class people whose best efforts were not enough to escape the trap set for them by society. They labored, they dreamed, and the establishment slapped them down like troublesome flies. Despite the fact that Hardy was writing at a time when a socialist critique of his society was being fashioned, he doesn’t seem to have a political message: Hardy was not a reformer but a mourner.

“Jude” is the second film I’ve seen by Winterbottom, whose “Butterfly Kiss” (1995) was a searing fable about a woman who was a schizophrenic killer and the simple-minded girl she dominated and loved during a murder spree. Hardy supplies appropriate material for him. On the basis of these films, Winterbottom is angry, clear-headed, and with a sure visual sense.

And his casting gives personalities to the characters. You may recall Eccleston as one of the yuppie killers in “Shallow Grave,” Griffiths was the heroine’s saucy girlfriend in “Muriel's Wedding,” and Winslet shows her range again this time, making Sue into a sassy, defiant woman who would rather be right than happy. Together they take a difficult story and make it into a haunting film.