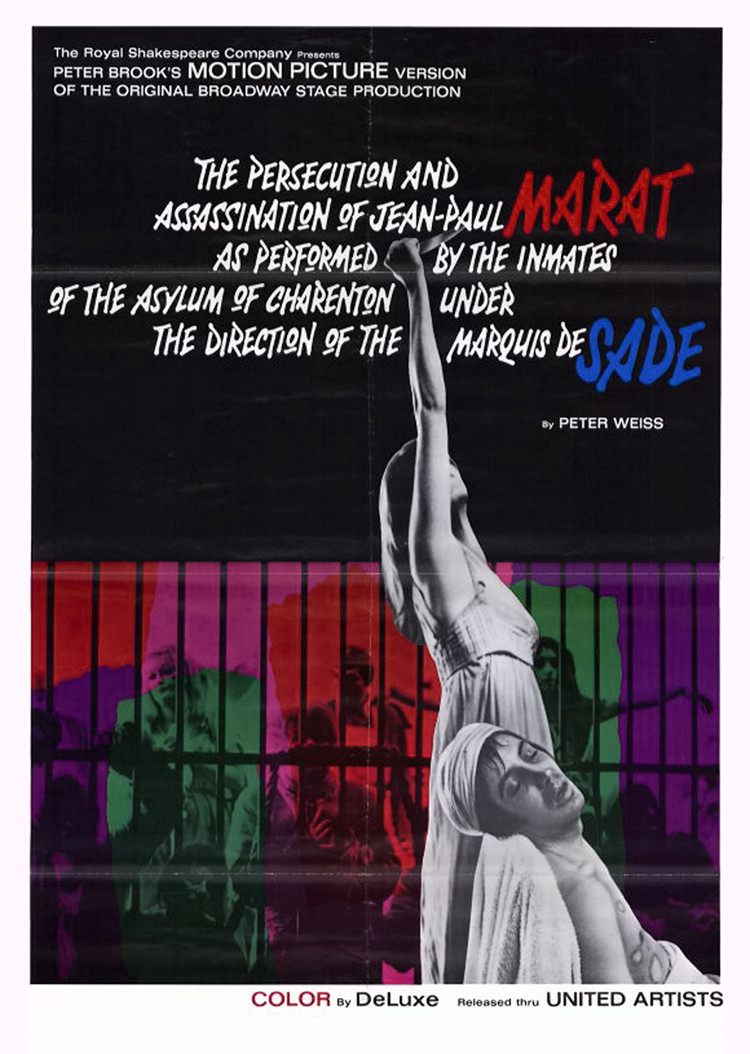

The problem of bringing a play to the screen has been approached in many ways, often disastrously, but it is hard to recall a film that solves it so triumphantly as Peter Brook’s “Marat/ Sade.”

Here was a vexing and difficult play, lacking entirely in the conventional kind of plot and suspense. Because of its peculiar structure, it made us aware at all times of the gap between the stage and reality.

At one level, the inmates of the asylum at Charenton were performing a play about the assassination of the French revolutionary figure, Marat. At the next level, we knew that the play was being directed by one of the inmates, the Marquis de Sade, for an audience of powdered and wigged members of Napoleon’s court.

At the third level was the tension during the production. Would the inmates, constantly distracted from the play by their various forms of insanity, be able to finish? Would they riot first? Would the director permit the Marquis’ subversive play to continue even if they did not?

Aand of course, there was the dramatic situation itself. Here was a play ostensibly being performed in 1808 by madmen, before an audience of reactionaries, 15 years after the revolution had died. Why should this situation be thought relevant to us in the middle of the 20th Century? Ah ha!

In Brook’s original stage production, the levels of the drama were made clear by the theater situation itself. Everyone was present in the flesh. Here were the inmates, putting on their play. Here was the Marquis de Sade, prompting the actors and defending his production to the outraged asylum director. Here were the director, his wife and daughter. And there, beyond the footlights, was the audience-of both 1808 and 1967.

But how could this dramatic situation be reproduced in a film, where the audience is accustomed to seeing everything and remaining unseen? I can think of two ways Brook might have approached the problem. He might have “expanded” the stage production, providing elaborate sets and dialog more straightforward than Peter Weiss’ terse, enigmatic, incomplete lines. He might, in short, have taken the stage play and written a screenplay “based” on it. He did not. He might also have become a purist, filming the play exactly as it was performed on the stage, as Gielgud and Burton did with their “Hamlet.” This would have preserved the stage production, a worthy aim, but it would have been a recording and not a new work of art. Brook also avoided this course.

Instead, he made a motion picture about a production of the play. He retained the original script, unaltered so far as I could tell. He used most of the members of the Royal Shakespeare Company in their original roles. He more or less reproduced the large communal cell of the stage production. Beyond the bars he placed an audience, which we see only in silhouette. He made one wall of the cell uniformly bright, supplying all the light for the filming.

And then, to what was still essentially a stage play, he added the techniques of cinema. The one power that a film director has, and a stage director does not, is the power to force us to see what he wants us to see. In the theater, we can look anywhere on the stage. But in the movies the camera becomes our eye and the director looks for us.

In “Marat/Sade,” Brook uses two cameras. One is high up under the ceiling, looking down dispassionately on the cell and the audience alike. The other is in the cage with the madmen, probing, investigating, whirling about to look at actors behind it.

When it faces into the light, the characters become surrealistic: There is nothing on the screen but a dazzling whiteness and uncertain green silhouettes that may be human. When it turns away from the light, we see every raw detail: The fever blisters on Marat’s skin, the gray stubble on the Marquis’ cheeks.

The actors are superb. When we first see the Marquis (Patrick Magee), he looks steadily into the camera for half a minute and the full terror of his perversion becomes clearer than any dialog can make it. Glenda Jackson, as Marat’s assassin Charlotte Corday, weaves back and forth between the melancholy of her mental illness and the fire of the role she plays. Ian Richardson, as Marat, still advocate violence and revolution even though thousands have died and nothing has been accomplished.

Brook has achieved the very difficult. He has taken an important play, made it more immediate and powerful than it was on the stage, and at the same time created a distinguished and brilliant film.